The attack on Clark Field, with which the Japanese had opened their offensive on the Philippines, had decimated the American Far East Air force (FEAF). Half of the FEAF’s vaunted B-17 Flying Fortress bombers had been destroyed on the ground before they had been able to launch a single raid on the Japanese, and most of the P-35 and P-40 fighters had likewise been destroyed by marauding Zeros. Whilst the remaining bombers had been withdrawn to Del Monte Field on Mindanao, a new base unknown to the Japanese, the remaining fighters were split between Lt Boyd D. Wagner’s 17th Pursuit Squadron at Clark and the 21st Pursuit Squadron at Nichols. With just 30 fighters still capable of flying, the decision was made to use these aircraft primarily for reconnaissance purposes – the observation aircraft usually assigned to this role had all been destroyed. The surviving B-17s would shuttle in to Clark to launch attacks when possible.

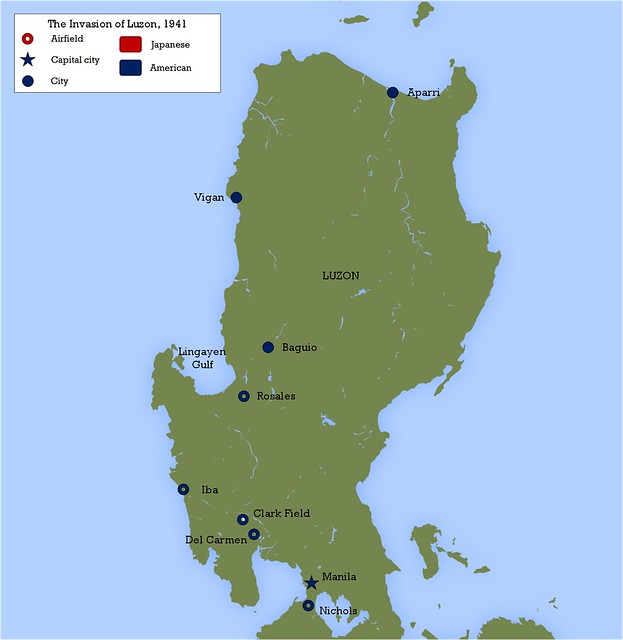

The Japanese took advantage of their early success and began to fly air units in to the Philippine Islands. The Army’s 24th and 50th Sentai flew their Ki-27s to Aparri, before moving on to Vigan which was closer to the Lingayen Gulf, where the main Japanese landings would soon begin. Other squadrons soon began to follow the 50th, but for now the Japanese Navy kept its long range A6M Zero fighters and Mitsubishi G3M and G4M bombers at their bases on Formosa.

Pressing the Attack

The of 11th of December opened with bad weather, so there were no operations other than reconnaissance sweeps by some of the C5Ms attached to the Tainan and 3rd Kokutai. The following day was equally unsettled, although half a dozen B-17s of the 19th Bomb Group did manage to get airborne, with five of them managing to reach Vigan where they attacked enemy shipping from high altitude with no hits recorded – further evidence of the inherent difficulty in hitting ships from three miles up. A P-40 piloted by the 17th PS commander Wagner had extraordinary success when he encountered a pair of Ki-27s over the Aparri airfield and shot both of them down, before repeating the trick by shooting down a second pair as they attempted to take off. He also strafed the parked aircraft on the field, leaving several burning. This was one the few successes that the American pursuit pilots could point to during the Philippine campaign.

On the 13th the weather was good, and so the 21st Air Flotilla could resume its bombing raids. The 1st and Kanoya Ku with their G3Ms and G4Ms attacked Clark Field and Iba Field, whilst the Takao Ku went after the small auxiliary airstrip at Batangas. The escorting Zeros as usual contributed to the attacks with strafing runs, which left 10 aircraft destroyed during the attacks.

The attack on Batangas was opposed by Boeing P-26 Peashooters of the Philippine Army Air Corps. These ancient, braced wing monoplanes had long since been discarded even by the ill-equipped FEAF, but the Filipino pilots put them to good use, claiming which claimed a pair of G3Ms shot down – one by Capt Jesus Villamor, commanding officer of the 6th Pursuit Squadron. A6Ms fell on the old P-26s, shooting several down, including the fighter of César Fernando Basa. As he descended on his parachute Basa was then machine-gunned and killed in an act of brutality which was not to be a unique incident in the Pacific War.

Several PBYs of Patrol Wing 10 were preparing for bombing raids on the Japanese invasion fleet after their unsuccessful attempts of the 10th. The flying boats were being bombed up and fuelled at the seaplane base of Olongapo, in Subic Bay, when Zeros swept in low and launched a strafing attack. Some of the PBYs had only useless practice ammunition to fire back with, but several gunners put up a spirited defense from their turrets assisted by the men of the ancient cruiser Rochester which was moored nearby. However, their efforts were in vain as all 7 PBYs at Olongapo were destroyed by the strafers. Having now lost 10 of their 28 PBYs, VP-101 and VP-102 were soon ordered to withdraw to Java, via Mindanao and Balikpapan, whilst the ground echelon boarded a captured Vichy freighter for the trip south. Once again American offensive power had been blunted before it could properly fight back against the Japanese invasion.

Civilian aircraft were also targeted by the Japanese as they began to take complete control of the skies over the Philippines. A twin-engined Beechcraft belonging to Philippine Air Lines was set upon by Zeros as it flew over Cebu in the central Philippines. Although the aircraft was badly riddled with bullets the pilot, a former US naval aviator named Paul “Pappy” Gunn, managed to land his plane at Nichols Field after jumpy gunners at nearby Zablan Field had opened fire on him. Gunn repaired his aircraft and eventually flew it out of the Philippines, leaving his family behind to face the occupying Japanese. Later, he joined the US 5th Air Force in Australia and was instrumental in developing new weapons and techniques that would be invaluable in helping to push back the Japanese.

The Japanese had landed troops at Legaspi in the extreme south east of Luzon on the 12th of December, and with the clearer weather they began to fly in Zero fighters of the Tainan Ku from Formosa. Six B-17s were launched from Del Monte to attack a carrier that was reportedly in the Legaspi area (this was the Ryujo, which was supporting the landings) but three aborted with mechanical issues. The remainder failed to find the carrier and dropped their bombs ineffectually on the transports offshore. They were then attacked by Tainan fighters, with one B-17 forced to crash land and another being severely damaged. After this failure, the B-17s withdrew to Batchelor Field in Australia. The following day, PatWing 10 was likewise withdrawn, to Ambon in the Netherlands East Indies. Their supporting tenders were withdrawn to Surabaya along with the reset of the Asiatic Fleet.

With US air power in the Philippines almost completely destroyed, the Japanese could roam almost at will over the archipelago. For the remainder of 1941 Army bombers could attack American and Filipino airfields whenever they chose, destroying the few aircraft that had not been able to make their escape to the south. American ground crews did their best to confuse the situation by rigging up crippled planes as decoys, even going so far as to build mockups from scratch to attract the attention of the bombers. The 14th and 50th Sentai were particularly concerned with attacking Del Carmen and Clark fields to prevent their use by B-17s shuttling in from Australia, and despite the best efforts of the defenders both facilities suffered further heavy damage.

In an attempt to do something to hit back at the Japanese, a mission was arranged for three P-40s to bomb and strafe the mass of Japanese fighter planes parked at the Vigan airfield. Led by the indomitable Lt. Wagner, the fighters arrived early on the morning of the 16th. Wagner commenced his run and destroyed several Ki-27s with bombs and machine guns, but the Japanese gunners were ready as his wingman Lt Russell M. Church followed. He was shot down and killed. The remaining pair completed several more strafing runs before one of the Japanese fighters managed to take off. Lt Wagner quickly shot it down, registering his fifth victory and thereby becoming the first American ace of World War II. Soon afterwards the 24th Sentai moved further north, in order to avoid a repeat of this attack.

More bad weather hampered air operations on both sides during the middle of December, curtailing most flights except for those by reconnaissance planes. On the 18th, Japanese sweeps over the central Philippines caught and destroyed several civilian aircraft including a Sikorsky S-43 flying boat of the Iloili Negros Air Express Company that was attempting to escape to the US. Meanwhile, the Army’s bomber sentai bombed Nichols and Zablan fields. On the following day, the Japanese finally discovered Del Monte field and launched strafing attacks by Zeros that forced the last remaining B-17s to pull out for Australia, and destroyed three B-18s. The FEAF in the Philippines was now virtually non-existent but for a handful of fighters scattered across Luzon.

Invasion: Davao

On the 20th the prohibition on offensive action by American fighters was lifted so that six of the remaining P-35s could be sent to attack a barracks building near the Vigan landing site. They successfully bombed and strafed the building, but on the way back to Clark one of the P-35s was shot down by a Ki-27. Also on the 20th landings began at Davao on Mindanao, covered by aircraft from the carrier Ryujo. Del Monte field was heavily raided by 54 Kanoya bombers in conjunction with this landing, but the last of the B-17s had been withdraw to the Netherlands East Indies the night before so damage was light. Japanese Army bombers also raided airfields on Luzon, but hardly any US aircraft remained on these fields either.

Nine B-17s of the 19th Bomb Group set out from Batchelor Field in Australia to hit the invasion fleet off Davao on the 22nd. They arrived at dusk, to the complete surprise of the Japanese, but their bombs caused limited damage to the shore installations at Davao port. On the 23rd, Zero fighters of the Tainan Kokutai were moved into Davao airfield, followed soon afterwards by H6K flying boats from the Toko Kokutai.

On 22nd, the main Japanese landings on Luzon began at Lingayen Gulf. Army bombers attacked several airfields to prevent any response from American fighters, whilst the 24th and 50th Sentai patrolled over the beaches. The Navy had also established a seaplane base at Vigan with several F1Ms, E13As and E7Ks – this being an early example of Japan’s use of floatplanes as auxiliary fighter-interceptors.

On the day of the invasion twelve P-40s from 17th and 20th Pursuit Squadrons set off to bomb and strafe the beaches. However, they got separated trying to form up in the pre-dawn darkness and only nine of the fighters actually made it to the beachhead. Arriving individually or in pairs, they carried out effective bombing raids on landing craft and boats that nevertheless did little to slow down the invasion. Lt Wagner’s P-40 was shot up by Ki-27s, and he was struck by a bullet in the shoulder as well as having his face showered with broken canopy glass. Wounded in the eye, he was guided back to Clark by his wingman – but his injuries meant that he was out of the fight for the Philippines.

In the days after the Lingayen Gulf landings the US forces under General MacArthur proved unable to stop or even slow the Japanese advance. Soon the Americans abandoned Manila and began to fall back to the Bataan Peninsula. A handful of P-35s and P-40s were assembled to attack a subsidiary landing at Lamon Bay, but after returning to base the American pilots were ordered to prepare for a rapid withdrawal to the new and secret Lubao airfield on the Bataan Peninsula – MacArthur was abandoning the rest of Luzon, leaving the American airfields to the Japanese. The planes that could get into the air were flown to Lubao as the ground crews boarded a steamer for bound for the tiny port of Mariveles, on the tip of the peninsula. Dozens of aircraft that could not be flown due to damage or lack of parts were burned to prevent their capture. At the same time MacArthur was told that no further air reinforcements would be sent to the Philippines – they would be held in Australia and fight from there.

And so ended the relatively brief fight in the skies over the Philippines. The handful of remaining fighters, along with a small contingent of utility aircraft left behind by Patrol Wing 10, would fight on from their bases in Bataan, assisted by occasional attacks by B-17s flying in from Australia. But the air war would soon move on to points further south as the Japanese offensive continued.

Leave a Reply