Kido Butai’s defeat at the Battle of Midway meant that American positions in the Central Pacific, including Hawaii, were now secure. US Navy Commander in Chief Admiral Ernest J. King now felt that the time was right to begin a counter-offensive, to take full advantage of the changing circumstances. He had long thought that the South Pacific was the key to blunting the Japanese offensive – if sufficient forces could be deployed to secure the lines of communication between the United States and Australia, then the area offered the perfect springboard for offensive operations against the key Japanese strongholds of Rabaul and New Guinea. This plan also had the advantage of keeping Allied forces in the Pacific active and engaged with the Japanese, rather than having them hold defensive positions until American industrial output allowed for a Central Pacific offensive to begin sometime in 1943.

On June 24th King cabled Admiral Chester Nimitz to warn him operations were due to begin far sooner than anyone had previously thought possible – Nimitz was informed that he should begin planning for an offensive into the Solomon Islands, targeting Tulagi and “adjacent areas” with a start date of August 1st. That left just five weeks to prepare for what would be the first Allied offensive of the war, into an area that was badly lacking in adequate harbours and airfields. To work out the finer details Nimitz flew to San Francisco for a conference with King, but the XPBS-1 flying boat carrying the admiral crashed on landing and he was lucky to escape with his life.

Nimitz had already carved out part of his vast command territory, the South Pacific, and appointed V.Adm. Robert L. Ghormley, as Commander, South Pacific (COMSOPAC). He would have overall command of the operation, but he had only taken command of the theatre in May 1942. Now he found himself with just five weeks to prepare his meagre forces. The only major ground forces available to Ghormley were M.Gen Alexander A. Vandegrift’s 1st Marine Division, but this unit was very green – most of the division was still on its way to New Zealand having left the US several weeks earlier. Several smaller units, including the Marine Raiders, the 1st Parachute Battalion, and the 3rd Defense Battalion with 90mm anti-aircraft guns, coastal defence guns and radar were attached the 1st Marine Division when the scope of their mission was expanded in mid-July.

More pressing was the lack of forward bases in the area. The major US forward base at Noumea had sufficient port facilities and a spacious airfield at Tontouta, but it lay almost 1,000 miles from Tulagi and could not offer adequate support to the marines. A fighter strip was under construction at Efate in the southern New Hebrides, itself 850 miles from the target area. Engineers raced to build another field at Turtle Bay on Espiritu Santo in the northern New Hebrides, which at 650 miles distant proved barely adequate as a base for B-17s and PBYs.

Land-based air support for the operation was under the command of RAdm John S. McCain. Elements of several Catalina squadrons from Patrol Wing 1 would provide reconnaissance, supported by the Flying Fortresses of the 11th Bomb Group. Tenders moved to Ndeni in the Santa Cruz islands to support the flying boats. For more direct support, the new Marine Air Group 23 was alerted for deployment to the Solomons once suitable airfields were captured. MAG-23 was only formed on 1st May and had just a handful of veteran pilots, the rest being rookies. VMF-223 and VMSB-232 formed the first echelon which boarded the escort carrier Long Island. VMF-224 and VMSB-242 were to follow when transportation was available. The Army’s 67th Pursuit Squadron was also based at Noumea, ready to move forward in support.

Heavy support for the landings would come in the form of VAdm Frank J. Fletcher’s Task Force 61, built around the carriers Enterprise, Saratoga and Wasp. Enterprise was by now a fixture of the Pacific War, having fought from the first day. Saratoga was returning to action following six months out due to torpedo damage. Wasp arrived in the South Pacific direct from the Panama Canal after an eventful period operating in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, where she twice delivered RAF Spitfires to the embattled island of Malta. All three carriers had an increased fighter compliment, with the standard VF squadron allotment of F4F Wildcats increased from 27 to 36 (although the smaller Wasp had just 30).

One invaluable service available to the invaders was Section C, Allied Intelligence Bureau, better known as the “Coastwatchers”. This was an organisation of mainly Australian and British civilians who lived in the Solomons and surrounding areas before the war, typically managing plantations or acting as colonial administrators. Many remained behind when the Japanese took over the islands, hiding in remote parts of the jungle and relying on the support of the native Solomon Islanders to remain hidden. Equipped with radios and commissioned into the naval services, the coastwatchers provided information about Japanese movements and sheltered Allied airmen who had to bail out over remote areas, amongst other roles. Key to the upcoming offensive would be Jack Read, based near Buka island off Bougainville, Paul Mason on southern Bougainville, and Martin Clemens on Guadalcanal.

Japanese opposition

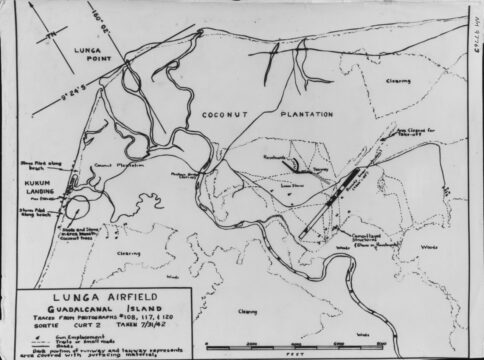

Meanwhile, intelligence received from British coastwatchers in the Solomons revealed that in early July the Japanese had cleared several coconut plantations on the northern coast of Guadalcanal, across Savo Sound from Tulagi, and were beginning construction of an airfield. Heavy construction equipment was shipped in, and it became clear that the airfield would be complete by early August. The plan for Operation Watchtower was altered and the “adjacent positions” in King’s original operation order were explicitly defined as Guadalcanal and the Lunga Point airfield. The Japanese had only 4,000 troops on Guadalcanal, most of them engineers and Korean labourers. Across Savo Sound on Tulagi were another 1,500 troops including several Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) troops.

The principal Japanese air units in the region were based at Rabaul, well over 500 miles distant from Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The 5th Air Attack Force, administratively the 25th Air Flotilla, had several units of veteran fliers. The crack Tainan Kokutai had many veteran fighter pilots and was primarily equipped with Zero fighters. The 4th Kokutai, which had been badly handled by Lexington’s fighters on February 20, 1942, was equipped with G4M bombers. The 2nd Kokutai was another fighter unit, but they were equipped with shorter range Model 32 Zeros (later known as “Hamp”) that could not make the flight down to Guadalcanal and return. There were also elements of the Yokosuka and 14th Kokutai with H6K and H8K flying boats, some of which were based at Tulagi, as well as small units of floatplane Zero fighters. The major bases were Lakunai on the shores of Rabaul’s Simpson Harbour for the fighters, and Vunakanau further inland for the bombers. A small number of primitive emergency fields existed in the Solomons, primarily at Buka on the northern end of Bougainville and Kieta on the same island’s eastern coastline. No Imperial Japanese Army Air Force units were deployed in western New Guinea.

Final preparations

With only old, inaccurate charts of the target area available, Vandegrift had two of his intelligence offers carry out an aerial reconnaissance to fill in the gaps. Marines Col Merrill B. Twining and Maj William McKean flew to New Guinea and managed to procure an AAF B-17 for the effort. On July 17, 1942, they set out to look at “Ringbolt” (Tulagi) and “Cactus” (Guadalcanal). Tulagi was eventually found no less than 40 miles from where charts thought it was, but it appeared that the reef surrounding the island would be impenetrable to small landing craft and therefore amphibious tractors would be needed. Several floatplane Zeros were spotted trying to get airborne to catch the B-17, so it turned south for a look at Guadalcanal. Here it was revealed that there were no fortifications on the Guadalcanal coast and the beaches were clear of natural or manmade obstacles. The now-airborne Zeros got close enough to fire off a few bursts, with fire returned by the B-17’s gunners, before the Americans broke off and headed for Port Moresby.

Despite the frantic pace of preparations, it was clear that the original deadline of August 1st was impossible to meet. Instead Ghormley deferred D-Day until August 7th. The marines sailed from Wellington on July 22nd aboard transports commanded by RAdm Richmond K. Turner, King’s handpicked choice to lead the amphibious force. On the 26th, the amphibious squadron made rendezvous with Fletcher’s carriers south of Fiji and prepared for a practice landing on Koro the following day. During the dress rehearsal a bombardment of the landing beach was carried out by cruisers and bombing attacks were conducted by carrier planes, but the landing craft could not pass over coral heads and the practice landings themselves were cancelled. Vandegrift deemed the exercise a “complete bust”.

Following this failure, Admiral Fletcher convened a planning conference aboard his flagship, Saratoga. Admiral Ghormley was not present, because he had decided to remain at his HQ in Noumea. Fletcher, Turner, Vandegrift and their senior staff officers discussed the upcoming operation at length but disagreed over key details. There was acrimony over the amount of time TF-61 would remain in the area to provide air support as the marines got themselves established ashore. Turner estimated that it would take 4 or 5 days to fully unload the transports and wanted a full 5 days of cover, but Fletcher, worried about exposing his precious carriers to air and submarine attacks that were sure to come, was prepared to offer only 2 days – although he later increased this to 3. After that there would be no air support until MAG-23 could be flown in when the Lunga Point airfield was completed by marine engineers. With Ghormley unavailable to referee the dispute Fletcher got his way over the opposition of Turner and Vandegrift. With that, the commanders headed back to make their final preparations.

The Task Force now numbered 82 ships, the largest naval formation assembled up to that point in the Pacific War. Departing Fiji on the 28th, the force set a south easterly course in order to approach Guadalcanal and Tulagi from the south. Bombing attacks on Guadalcanal and Tulagi were carried out by the 11th Bomb Group – 9 B-17s struck on 31st July, flying from Efate to bomb the airfield at Lunga and disrupt construction works. A smaller raid the following day destroyed a pair of floatplane fighters, but an attack on the 4th was more difficult for the Americans. Three B-17s were intercepted by Zero floatplanes, one of which was damaged by the Flying Fortress’ gunners. The stricken fighter smashed into a B-17 and both aircraft went down. The next day another B-17 was lost in an attack on Tulagi.

On August 5th the ships turned north to begin the final run in, and Fletcher’s carriers broke off to take their supporting positions whilst the transports continued west of Guadalcanal before turning east into Savo Sound. There were no contacts with enemy ships, and radar screens remained blessedly clear of patrolling aircraft. As dawn broke on the 7th, D-Day, it was clear that the Americans had achieved complete surprise.

Leave a Reply