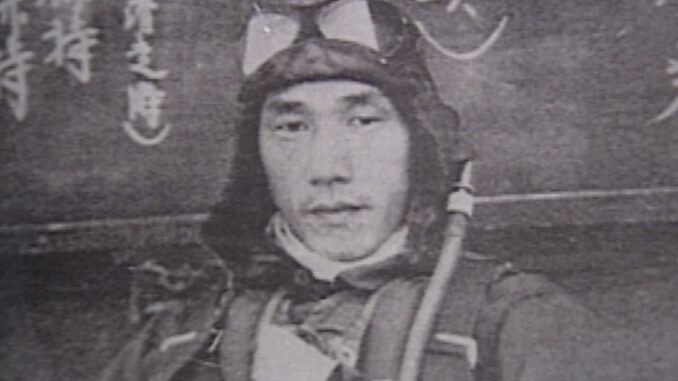

When I-25 arrived at her berth in Yokosuka harbour, her pilot, Nobuo Fujita, was surprised to receive orders to report to Naval General Headquarters in Tokyo. At first he feared that he was to be disciplined for some forgotten reason, but when the meeting of the Naval General Staff’s First Bureau convened he was surprised to see the familiar figure of Prince Takamatsu, Emperor Hirohito’s younger brother, amongst other luminaries. Takamatsu was himself a distinguished naval officer. As the meeting came to order, Fujita was informed of the reason for his presence – “You are going to bomb the American mainland!”

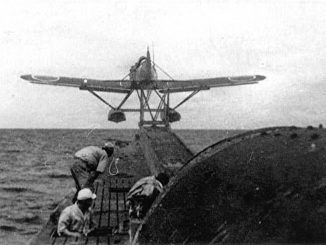

This order was perhaps not as surprising as it at first seems at first glance. Months before, Fujita had written a proposal for such an undertaking and submitted it to the senior officers of the I-25. The submarine’s executive officer, Lt Tatsuo Tsukoda, had endorsed the plan and it had been eventually percolated its way up the chain of command. And now in July 1942, with the pain and embarrassment of the defeat at Midway uppermost in Japanese minds, the plan was given the go-ahead. Aware that the tiny, slow Yokosuka Type 0 was unsuited for attacks on military bases or well-defended cities, the planners opted instead for an attack on an area of forest in southern Oregon. It was hoped that even a small attack could trigger an enormous forest fire that could consume nearby towns and cities.

The “Lookout” Raids

On August 15 the refuelled and refitted I-25 departed Yokosuka and headed east once more. In addition to Fujita, Okuda and their E14Y, the submarine carried a special cargo of six 76-kg incendiary bombs that were destined to be dropped on American soil. By early September I-25 was off the west coast, where on the 4th she unsuccessfully attacked an unidentified transport ship. On the 7th Fujita was due to begin his attack, but appalling weather put paid to these plans and the I-25 was forced to endure heavy waves for two days, until the weather broke. Unbeknownst to the Japanese, this storm also soaked the target area with unseasonable levels of rain.

Before dawn on September 9, I-25 arrived at the launch position 25 miles off the Oregon coast. Fujita and Okuda climbed aboard their E14Y, which was carrying two of the incendiary bombs, and catapulted off the submarine just after dawn. The tiny plane flew over the town of Brookings, and towards the nearby Mount Emily in the Siskiyou National Forest. In the dense forests beyond, Fujita released first one and then the other of his bombs, before returning back to the coast. Altogether Fujita spent barely 30 minutes in American airspace.

The presence of the Japanese aircraft had been noted by early-rising Forest Service ranger, who noted an engine that sounded like a “Model A Ford backfiring”. The same ranger, Howard Gardner, later reported a plume of smoke near his lookout station. He was ordered to find the source of the smoke and extinguish the fire, being joined by three other rangers. After several hours of hiking the rangers found many small fires around a small crater, clear evidence of a bomb. The fire was quickly extinguished, but the location of the second bomb was never determined. In any event, there was no large conflagration, and no damage caused by Fujita’s attack.

Nevertheless, the bombing caused a degree of consternation on the coast, albeit for less than the December 1941 panic that became known as the ‘Battle of Los Angeles’. The attack made the news on both sides of the Pacific, with the Los Angeles Times declaring “Jap Incendiary Sets Forest Fire” and Asahi Shimbun’s headline triumphantly announcing “Incendiary Bomb Dropped on Oregon State. First Air Raid on Mainland America. Big Shock to Americans”. In response, the Army’s Western Defense Command investigated the attack with the assistance of the FBI. Air patrols were stepped up, and the day after the bombing an A-29 Hudson bomber from McChord Field spotted I-25 on the surface. LtCdr Tagami was able to execute a crash dive, but the bomber nevertheless managed to release several depth charges which caused minor damage to the submarine.

Three weeks after the first attack, on September 29, Fujita tried again. This time the target was an area of forest near Port Orford, a town about 50 miles north of Brookings. This attack achieved even less than the first, with no reports of any fires being started and just a few sightings of the E14Y. Although there were still two incendiary bombs remaining, opportunities to drop them failed to materialise due to poor weather. Instead, I-25 remained in the area for several more days, preying on unescorted shipping. In October 4 she came across the tanker Camden, which had stopped to make repairs to her engines. I-25 dived and fired two torpedoes, one of which hit the tanker and caused her to settle. She soon sank, with a single crewman killed but the remainder rescued. Two days later another tanker was sighted, the Larry Doheny, and torpedoed at short range. A fire quickly broke out forcing the crew to abandon ship, before the Larry Doheny slipped beneath the waves.

Reconnaissance and Supply

Low on torpedoes, LtCdr Tagami set course to return to Japan. On October 11 as she withdrew from the West Coast, I-25’s lookouts spotted two warships on the surface, which were soon identified as two American submarines. Tagami gained a good launch position and fired has last torpedo at the lead vessel. It hit, and soon secondary explosions rocked the I-25. In fact, this submarine was not American but was the Soviet L-16, enroute from Petropavlovsk to northern Europe via San Francisco and the Panama Canal. She sank with all 55 of her crew and an American liaison officer. Her sister ship L-15, following, attempted to attack the I-25 with her deck guns but failed to cause any damage. Two weeks later, I-25 reached Yokosuka and entered overhaul.

When she was ready for sea once more, I-25 was assigned to the submarine flotilla engaged in resupply missions to the beleaguered Japanese garrison on the northern coast of New Guinea. Her E14Y was left behind so that more cargo could be carried in the aircraft hangar. She made four successful voyages, ferrying in supplies and evacuating sick and wounded troops as well as surviving a torpedo attack from the American submarine Grampus. American torpedoes were still extremely unreliable and the single ‘fish’ that struck I-25 was a dud. Soon afterwards she was reassigned to a Truk, where, as 1943 opened, she would resume her career as a combat warship with her floatplane back aboard.

Operating off the Solomon Islands during the Japanese withdrawal from Guadalcanal, I-25 was unable to get into position to attack American warships during the Battle of Rennell Islands, during which the cruiser Chicago was torpedoed and sunk by Mitsubishi G4M bombers. In the aftermath of the Guadalcanal withdrawal I-25 was ordered to perform a reconnaissance of Espiritu Santo, an American air and naval base through which reinforcements for the Solomons flowed. On February 16 she arrived in the vicinity, and launched her floatplane in the late evening for a night reconnaissance. Several months later, in August 1943, I-25 was ordered to repeat her reconnaissance of Espiritu Santo. On August 23 her floatplane again took to the air, this time reporting the presence of three ‘battleships’ as well as smaller vessels.

This report was the last message to be received from the I-25. She was ordered to carry out another reconnaissance flight of Suva, Fiji, in September, but she did not acknowledge the message and was soon presumed lost. Her fate remains unknown but in all likelihood she was sunk by the American destroyer Patterson on August 25. Patterson was escorting a convoy from New Caledonia to the Solomons. As night began to fall she obtained a radar surface contact and moved to investigate. The radar ‘blip’ disappeared but Patterson soon obtained a sonar contact and began a series of depth charge attacks over the following two hours. Following the last of these a large underwater explosion was heard, and the following morning a large oil slick was seen on the surface. Although this was assessed as a damaging attack only, it seems that in fact Patterson’s target was the I-25, and that she was destroyed, sinking with all hands.

Leave a Reply