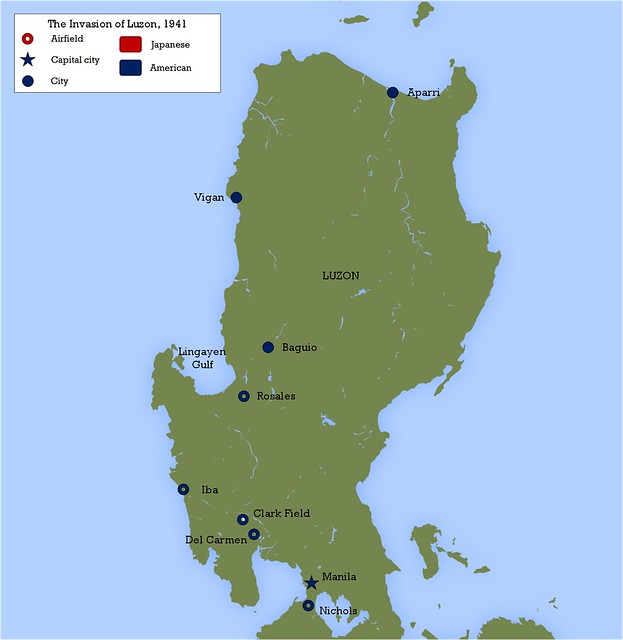

The American Far East Air Force (FEAF) was the largest USAAF command outside of the US. In 1940 the FEAF had a pitiful collection of outdated and obsolete P-26 fighters and B-10 bombers, both completely inadequate to defend the Philippines against any competent opposition. During 1941 the strength of the FEAF was greatly increased as new aircraft arrived. The first of these were Seversky P-35s, diverted from a Swedish export order, but these were soon followed by B-18 bombers and P-40 fighters, the latter being the first truly modern military aircraft in the islands. Finally, in September 1941, the first B-17 heavy bombers arrived at Clark Field having crossed the Pacific from Hawaii. By the time of Pearl Harbor the FEAF counted 35 B-17s of the 19th Bomb Group and around 90 P-40s and 26 P-35s of the 24th Pursuit Group, as well as numerous surviving older aircraft – some of which had been assigned to the Philippine Air Force. However, many US pilots assigned to the FEAF had only recently completed their training, but due to the rapid expansion of the AAF the quality of training was sometimes inadequate. A second bomb group was expected to arrive from the US in mid-December, so half of the bomber force was stationed at Del Monte, on the southern island of Mindanao, to make room for the newcomers. Further reinforcements were either en-route to the Philippines or were earmarked for the FEAF, including the 27th Bomb Group with their A-24s (Army versions of the SBD dive bomber).

The Navy had their own air unit – Patrol Wing 10 with two squadrons of PBY Catalina patrol bombers and a section of utility floatplanes, with several seaplane tenders and land bases spread throughout the islands. The Marine Corps were responsible for the management of one of the two SCR-270 radar sets in the Philippines, which was set up at Cavite Naval Base on Manila Bay. Another set was under USAAF control at Iba Field, on the west coast of Luzon.

The principal Japanese force tasked with supporting the Army’s landings in the Philippines was the Navy’s 11th Air Fleet, based on Formosa. Two air flotillas were attached for the operation, altogether comprising around 300 aircraft. The 21st Air Flotilla had three units of bombers: the Kanoya Kokutai with G4Ms; the 1st Kokutai with older G3Ms; and the Toko Kokutai with H6K flying boats. The 23rd Air Flotilla counted amongst its strength the Takao Kokutai with more G4Ms, and the Tainan and 3rd Kokutai, with over 100 A6M Zeros and several C5M reconnaissance models between them. Experimentation with the Zero’s engine settings had revealed that it could easily traverse the 550 mile distance from Formosa to the Manila area and back, and so the use of these fighters became a critical component of the Japanese plan.

The Japanese Army also contributed a large force to the invasion. The 5th Air Group included two sentai of Ki-27 fighters (the 24th and 50th), one of Ki-21 heavy bombers (the 14th, which was temporarily detached to support the Hong Kong operation) and two of Ki-30 and Ki-48 light bombers (the 16th and 8th Sentai, respectively). The 5th Air Group’s fighters could not match the endurance of the Zero, and would therefore initially concentrate on patrolling over the invasion convoys before transferring to Northern Luzon.

“Air Raid Pearl Harbor”

At 0300 local time on the 8th of December, the famous ‘Air Raid Pearl Harbor’ message was received in the Philippines. The FEAF was instantly put on alert, with pilots ordered to stand by their aircraft. Within 30 minutes, unidentified aircraft were detected by Iba’s SCR-270 radar set and P-40s were sent to intercept, but they failed to find the incoming aircraft (probably reconnaissance patrols) in the darkness. At 0500, official word came from the US that the war was underway. When notification of the Pearl Harbor raid was received, the FEAF’s commander Lt.Gen. Lewis H. Brereton immediately requested permission to send his B-17s to attack Japanese airfields in Formosa. He was unable to talk to MacArthur to gain authorisation, so as a precaution had his B-17s take off to prevent them being caught on the ground. Shortly afterwards a large formation was aircraft was discovered coming in from the north.

This formation was a strike that had been launched in the early hours. Japanese Army bombers arrived over northern Luzon around 0800, as the 8th Sentai attacked Tuguegarao airfield and the 14th Sentai’s Ki-21s bombed Baguio barracks. As with the earlier contacts Iba’s radar set had detected the intruders but Brereton’s P-40s were deployed to protect what were deemed the most important facilities in the Philippines – Manila and Clark Field – not Baguio, and so the bombers were able to complete their attack unmolested. Davao on the southern island of Mindanao was also bombed by aircraft from the small carrier Ryujo, with two of PatWing10’s PBYs destroyed on the water. Thick fog covering Japanese Navy airfields on southern Formosa delayed the launch of the 11th Air Fleet’s own bombing raid by several hours, the planes not departing until 0930 – less one bomber which crashed and exploded during the takeoff.

Eventually, MacArthur contacted Brereton and authorised the strike on Formosa. The B-17s were recalled to Clark to refuel and bomb-up for the mission. Most of the fighter aircraft that had been launched before the 5th Air Group’s raids were also running low on fuel and had to land, and the 3rd Pursuit Squadron which had been sent on a fruitless hunt over the South China Sea was ordered to return. Therefore the vast majority of the FEAF was on the ground when the 11th Air Fleet’s bombers arrived just after 1pm. Flying in perfect V formations the Japanese bombers were completely unopposed.

The 20th Pursuit Squadron, based at Clark, attempted to get its P-40s off the ground when the raid was spotted. Only four of the fighters got airborne before 53 Japanese bombers began to rain down their ordnance, with 34 fighters of the Tainan Ku swooping in to add their firepower. Five P-40s were destroyed by the bombers as they attempted to take off, and another five were destroyed in their parking area. The damage to the base facilities was extensive and several of the 24th Pursuit Group’s pilots had been killed, but miraculously most of the B-17s remained undamaged by the bombing. However, marauding Zeros soon came in to strafe, shooting down several P-40s that were hurriedly trying to get into the air. They then concentrated on the big bombers, quickly destroying most of them. A B-17 arrived over Clark in the midst of the attack having flown up from Mindanao; it was shot up by the Japanese fighters but managed to fly all the way back to Del Monte with severe damage.

The P-40s of the 20th Pursuit Squadron claimed 3 Japanese planes shot down, the first of these by 2Lt Randall D. Keator. His victim was probably NAP3c Yoshio Hirose of the Tainan Ku. The 34th Pursuit Squadron at nearby Del Carmen airfield saw the smoke from the raid and tried to get airborne in their P-35s to assist – several of these were attacked and damaged by the Japanese, but claimed 3 of the enemy without loss. The Japanese claimed to have destroyed 25 planes in the air and 49 on the ground at Clark.

Meanwhile the 3rd Pursuit Squadron was returning from their South China Sea patrol just as a second formation of Japanese bombers arrived at Iba Field. Low on fuel and unable to escape, five of their P-40s were shot down and three others were forced to crash land due to fuel exhaustion. As at Clark, the escorting Zeroes (this time of the 3rd Ku) descended to strafe, adding to the destruction caused by the bombers. At Iba the Japanese claimed 30 aircraft destroyed on ground, an exaggeration but nevertheless reflective of the state of the American situation. Only two of the 3rd Pursuit Squadron’s P-40s survived at Iba, and critically the air search radar set was also destroyed – no further warning of incoming raids was likely.

Clark Field’s facilities had been badly battered. The damage included the destruction of the communications centre, which prevented calls for reinforcement from neighbouring fighter units from going out. 55 men were killed on the ground. 18 B-17s, representing half of the FEAF’s bomber force, were destroyed. The Americans had lost the ability to operate offensively against the Japanese on Formosa. 55 of the P-40s, more than half of the fighter force, had been lost in the two attacks, plus several P-35s and many of the older twin-engined bombers and observation craft had also been lost. The Japanese lost half a dozen Zeros and a single G4M that crash landed upon its return to Formosa.

Fortunately the Americans were given a reprieve on the following day. More thick fog of the sort that had delayed the 11th Air Fleet on the first day of the war almost completely grounded the Japanese, with just 9 G3M bombers getting into the air. These bombed Nichols Field before dawn, damaging a pair of B-18s but otherwise causing little damage. However, during the night of the 9th/10th December a more serious threat was discovered by the Americans – a P-40 on a reconnaissance mission discovered a Japanese invasion fleet heading for Luzon. The pilot of the P-40 was shot down by anxious gunners upon his return to Nichols, but parachuted to safety and was able to make his report.

Invasion

Five PBYs of Patrol Wing 10 took off to attack the invasion fleet, delivering a high-level bombing attack that appeared to damage a cruiser (actually they had near-missed the Ashigara), but otherwise failed to drive off the Japanese. These were followed by five B-17s which, having staged from Mindanao, attacked Japanese shipping that was engaged in unloading operations off Vigan, where landings were taking place. FEAF fighters then came in to strafe the invasion fleet, these badly damaging the Takao Maru which was beached and later finished off by Filipino guerrillas. Minesweeper #10 was also strafed by Capt Samuel H. Marrett, commanding officer of the 34th Pursuit Squadron. When this ship blew up following his attack it ripped the wing off his P-35, causing it to crash. Marrett was killed.

Five more high-flying B-17s then came in to attack the transports offshore, but fail to hit anything – this being perhaps the first evidence of the B-17s inability to hit ships at sea. The last B-17 was commanded by Capt. Colin Kelly, who made a solo run on a ‘battleship’ that was probably a minesweeper or perhaps the heavy cruiser Ashigara. It was erroneously claimed that Kelly had put a bomb ‘down the smokestack’ of the battleship and sunk it. Kelly then returned to Clark but his bomber was pounced upon by a flight of Zeros led by Nap1c Saburo Sakai and heavily damaged. All of the crew except for Kelly were able to get out of the stricken B-17 before it crashed, but Kelly perished. He was later awarded a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross for his efforts and was feted as one of the first American war heroes.

The Americans were not the only ones to be launching heavy attacks on the 10th. Following the wash-out of the previous day, the entire 11th Air Fleet was despatched to the Manila Bay area, where they would concentrate on the naval and air facilities around the capital. Just after midday, the attacks began. As the attack force approached the area, Tainan Zeros descended to attack Del Carmen Field. Here the P-35s of the 34th Pursuit Squadron were caught on the ground, with a dozen of their fighters destroyed and others damaged. P-40s from Clark were scrambled to head off the bombers, but despite claiming several fighters shot down they failed to interfere with the attacks.

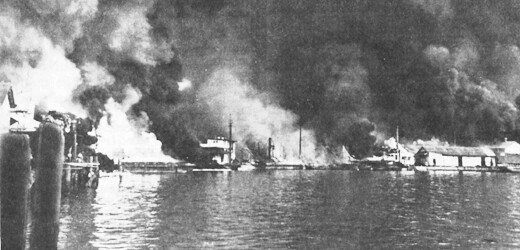

The older G3Ms of the 1st Ku were assigned to attack Cavite Navy Yard; they began their attack at 1230. The results were particularly effective, with the base’s depot area being hit hard – over 200 of the Asiatic Fleet’s submarine torpedoes were destroyed when their storage area was hit by bombs. The Cavite power plant was also destroyed, depriving the base of electric power. The submarine Sea Lion, immobilised due to repairs to her engine, was hit by two bombs which caused severe damage and killed four sailors. Damaged beyond repair, with the Japanese closing on Manila, the submarine was scuttled on Christmas Day. Attacks on Nichols, Zablan and Maniquis airfields destroyed several aircraft on the ground, mainly ancient models long since handed down to the Philippine Air Force. Army Ki-21s also paid a visit to Iba to add to the destruction there.

Three days into the war, the American military situation in the Philippines was shambolic. The much vaunted B-17 force had been shattered, with the remnants forced to withdraw to Mindanao to preserve their now limited numbers. Just 30 fighters remained serviceable, but these would be hard pressed to put up much of a defence against the waves of Zeros flying in from Formosa and were therefore reserved for reconnaissance. Patrol Wing 10 still retained most of its strength but would soon be withdrawn along with the remaining US Navy ships, which began to pull south to join the British at Singapore. With the way cleared for the Japanese invasion fleet and no sign of reinforcements arriving from the US, the writing was already on the wall for the Americans.

Leave a Reply