Despite mounting perhaps the longest and most sustained bombing campaign against a single city, the Japanese had failed to force China out of the war. Operations 100 and 101 had caused tremendous destruction to Chungking’s industrial and civilian areas but had failed to persuade Chiang Kai-Shek and the Kuomintang to capitulate. The Chinese Air Force proved unable to fend off the raids consisting of increasing numbers of G3M bombers, a task made even harder by the arrival of the A6M ‘Zero’ in September 1940. Still, the Chinese fought on and so the Japanese decided to use the bombing season of 1941 to mount their biggest series of attacks yet on the capital. Operation 102 would see more bombers mount even more sorties, with more escorts, than any other campaign of the China war.

To co-ordinate what would become a gargantuan effort, the brand new 11th Koku Kantai, or Air Fleet, was formed on the 15th of January, 1941. This unit would have overall control of all of the ‘rikko’ units in China, as well as training units in Formosa and Japan. Two newly formed G3M units, the Mihoro and Genzan kokutai, were the first to join the 11th Koku Kantai, later being joined by the new 1st and 3rd Ku. The veteran Kisarazu Ku would eventually be permanently stationed on Formosa as a training unit, turning out complete crews for the G3M and later the G4M bomber.

Whilst the ‘rikkos’ were organising themselves in preparation for the summer’s bombing season, the tactical units were busy consolidating their positions. From Hankow and Ichang the 12th Ku, with its single engine D3A and B5N bombers, continued to put pressure on the Chinese. In an attack on Chengtu on the 14th of March, 31 Chinese I-153s of the 3rd and 5th Pursuit Groups attempted to intercept a formation of 10 B5Ns escorted by a dozen Zeros. The Zero pilots continued to display the dominance that had marked their appearance in China the year before, and promptly shot down 11 of the biplanes without loss. Thereafter the Chinese Air Force was again ordered not to attempt to attack the Japanese when the superior Zeros were present.

The Chengtu Zero

The Zero was not invincible, however. On the 20th of May 30 of the fighters swept over the airfields of Chengtu, strafing aircraft and personnel on the ground. One of them, piloted by Petty Officer Eichi Kimura, was badly hit by anti-aircraft fire and during the subsequent crash-landing the pilot was killed. The aircraft was reasonably intact, and intelligence reports about the fighter were quickly dispatched to the British and American governments. Unfortunately for the Allies the tail of the Zero was badly damaged so the officials who captured the wreck ‘estimated’ the aircraft’s silhouette by drawing on the tail shape of a Ki-27 to the sketches – the end result looked very similar to the Nakajima Ki-43. This would cause much confusion during the early months of the Pacific War. Otherwise the Chinese were able to provide accurate performance specifications for the fighter, but these seem to have largely been ignored or not believed by the Allied air forces.

Despite this setback the Zero continued its dominance of the skies over China. The rikko units of the 11th Koku Kantai arrived in mid-June and began a series of raids designed to whittle down the Chinese Air Force prior to the commencement of the main campaign against Chungking. On the 21st of May the new Mihoro Ku flew to Lanzhou to bomb the airfields, losing a G3M to a flight of four I-153 fighters. The attack was repeated the following day, with several I-16s being damaged on the ground – the Chinese managed to bring own another bomber, however. The 12th Ku’s Zeros, meanwhile, were in action the same day over Chengdu, strafing the city’s airfields and claiming and SB bomber shot down. The 12th then made a long range attack of their own on Lanzhou, burning out dozens of enemy aircraft on the ground.

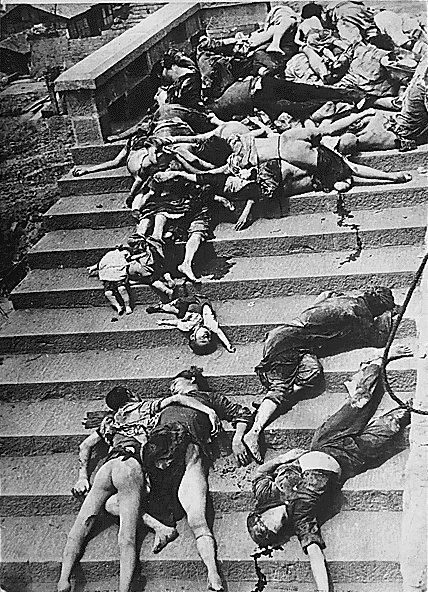

The attacks on Chungking began in June. On the 5th, 27 G3Ms attacked the city in three waves, with the attack lasting for hours. Tragedy ensued when the citizens headed for the emergency tunnels, as over a thousand civilians were killed due to suffocation or crush injuries in the Jiaochangkou tunnel. The following day the 12th Ku struck again, catching a pair of Chinese fighters over Chungking and destroying them. Attacks on Lanzhou continued throughout the month, with the Zeros getting the better of Chinese pilots whenever they were encountered in the air, or burning them on the ground if they declined to rise to meet the attackers. On the 23rd, whilst escorting a pair of C5M reconnaissance planes to Lanzhou, an A6M piloted by Petty Officer Kichiro Kobayashi was shot down by a heavy anti-aircraft barrage.

Chungking was continually pounded during July as the 11th Koku Kantai got into their stride. Attacks increased in size as additional G3M kokutai arrived at Hankow, and towards the end of the month the Takao Kokutai arrived with their brand new Mitsubishi G4M bombers. The deployment of these aircraft had been delayed by a year due to a misguided attempt to turn them into a long range escort aircraft, but they would go on to become the primary land-based bomber of the Japanese Navy. The first mission of the G4Ms was an uncontested attack on Chungking on the 27th, followed by their participation in a 108 bomber raid the following day during which a trio of I-153s were shot down by the escorting Zeros.

Diplomatic Incidents

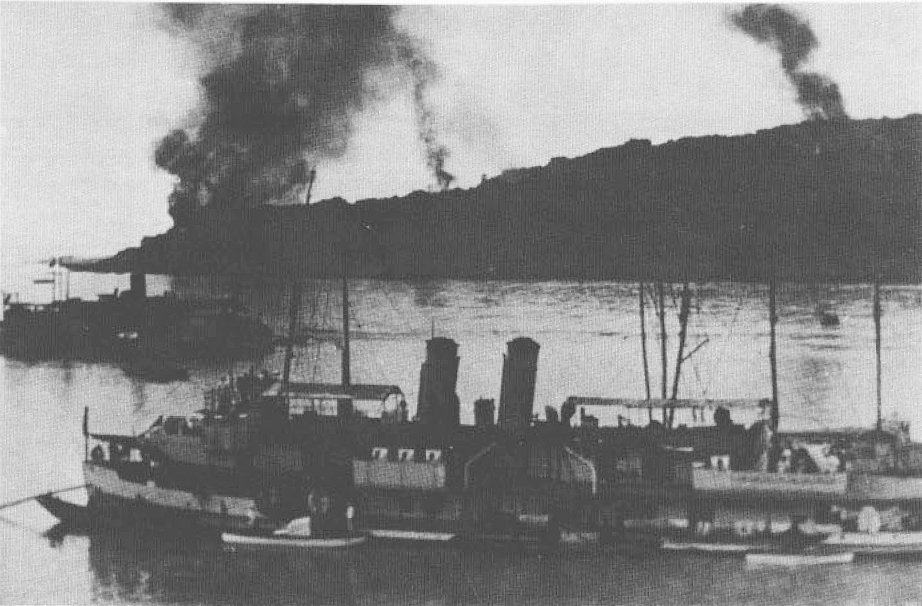

On the last day of the month there occurred a diplomatic incident reminiscent of the Panay Incident of 1937. The US Embassy on the south bank of the Yangtze opposite Chungking had repeatedly suffered damage during the raids on the city, though thankfully there had been no casualties amongst the staff. Moored on the river close to the embassy was the gunboat Tutuila, assigned to the US Navy’s Yangtze River Patrol. On the 30th of July the Japanese appeared over the city as usual, but this time the bombs fell alarmingly close to the Tutuila and to the embassy complex. One bomb exploded just yards from the gunboat’s stern, holing her at the waterline and destroying her motorboat. Other bombs killed Chinese embassy workers. The US ambassador complained to the Japanese, who claimed that the bombing was accidental, and demanded $27,000 dollars in compensation for the damage.

The Tutuila incident was an example of the rapidly deteriorating relationship between the United States and Japan. Public opinion in the US was already antagonistic towards the Japanese as a result of the atrocities committed during the China war, and the political and military leadership began to take the threat in the Pacific seriously as Japan moved south into Indochina – a move which put Japanese units within striking distance of the US-controlled Philippines. Having secured the use of military bases in northern Indochina in 1940, the Japanese moved south to control key airfields and ports in August 1941. This finally persuaded President Roosevelt to take action and he extended various embargoes on Japan to include strategic oil and steel imports. This action could be considered a de facto act of war, and it set in motion a series of political and military discussions in Japan which put the country on the path to war with the US.

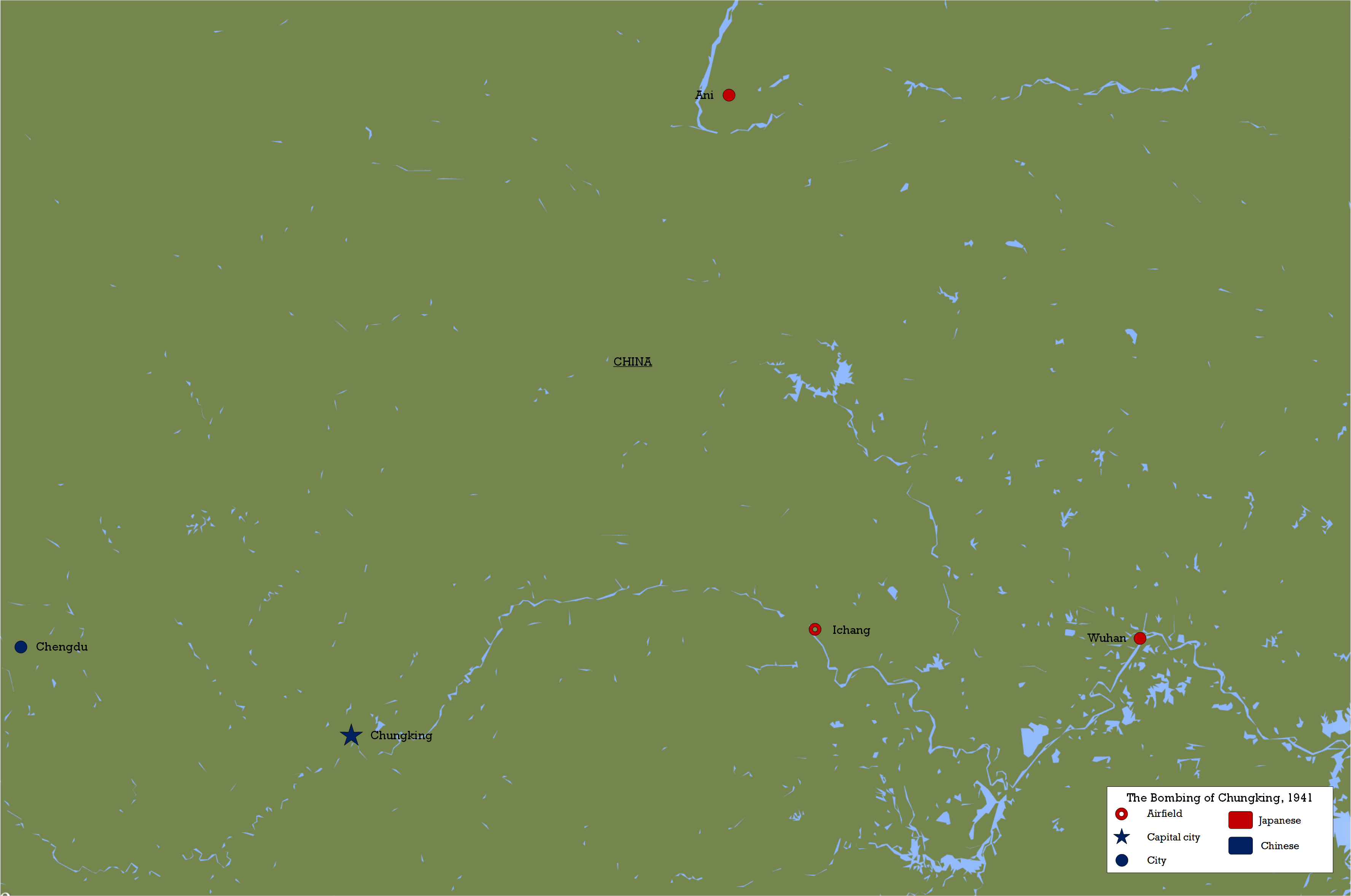

The bombers of the Japanese Naval Air Service were once again joined in their attacks on Szechwan province by the Ki-21s of the Japanese Army. The 12th, 60th and 98th Sentai with their supporting reconnaissance units were based in Hankow and the city of Ani to the north, both being within range of Chungking. The bombers were joined by the Army’s answer to the Navy Zero – the brand new Nakajima Ki-43 ‘Hayabusa’ (Peregrine Falcon) which was beginning to replace the Ki-27. The 59th Sentai was the first to arrive with their new mounts, but quickly discovered that unusual folds were beginning to appear in their aircraft’s wings. Similar problems were encountered by the 64th Sentai at Canton, and as a result all Ki-43s were recalled to the factory for modifications before having the chance to make much of an impact on the China War.

Operation O-Go

With the Chinese fighter forces determined to avoid combat with the superior Zero, the Japanese were forced to turn to unusual tactics. On the 10th of August “Operation O-Go” was launched. The plan was for the new G4Ms to act as formation leaders to a flight of A6Ms, which would fly through the night with the intention of surprising the Chinese on the ground as dawn broke. This was possible due to the faster cruising speed of the G4M, which allowed the Zeros to keep formation with the bomber without having to weave – an important consideration during night flights. On the first day of the operation the Japanese appeared over Chengdu at dawn and surprised the Chinese, shooting down a fighter of the 21st Pursuit Squadron that attempted to intercept. The next day in an attack on the same city, the 12th Ku shot down five I-153s of the 29th Pursuit Squadron, killing three of the pilots in the process. Four more of the biplanes were destroyed on the ground by strafing Zeros, as well as a pair of SB-2 bombers.

In mid-September, with Japan-US relations souring rapidly, Operation 102 was curtailed. The 11th Koku Kantai was with withdrawn from China to begin preparations for the “Southern Operation”, the attacks on American, British and Dutch possessions in the South Pacific. The experience gained by the rikko units would be demonstrated during the first month of the Pacific War as the Japanese swept aside Allied air power in the region. Likewise the IJAAF bomber Sentai were redeployed to the newly occupied airfields of southern Indochina, from where they could easily reach the British strongholds of Singapore and Rangoon.

During the three summers of bombing that comprised Operations 100, 101 and 102, the Japanese had mounted a total of 164 raids totalling 7,452 sorties. The raids had succeed in killing over 10,000 people, wounding another 12,000, and destroying over 33,000 homes. The Chinese Air Force, already badly mauled during the retreat from Shanghai to Chungking, was a shadow of its former self despite the imported supplies of Soviet aircraft and pilots and would not be rebuilt until US Lend-Lease supplies began to arrive in significant quantities during 1943-44. Despite this, the bombing campaign had failed in its primary goal of forcing the Chinese out of the war – an early example of evidence that the ‘bomber barons’ were wrong. Bombing alone could not win a war, unless it was mounted on a scale that was so destructive that it would almost redefine war.

Leave a Reply