Operation 100 had proved that the Japanese had the capability to conduct a sustained bombing campaign against Chinese cities, however it had also proved that the effectiveness of these raids was questionable. The government of Chiang Kai-Shek proved to be resilient enough in the face of the attacks, and despite the thousands of civilian casualties morale in the cities of Chungking and Chengtu had not been crushed under the weight of Japanese bombs. Moreover, the Chinese Air Force retained some ability to protect the cities from the G3M and Ki-21 bombers that formed the main strength of the Japanese bomber force – Soviet made I-15 and I-16 fighters were able to inflict consistent, if moderate, losses during the attacks.

For the spring and summer of 1940, the Japanese planned to redouble their efforts in a bid to force the Kuomintang to capitulate and bring the war in China to an end. What followed would be the longest sustained bombing campaign that the Japanese attempted during the entire war, one with no military objectives but a clear aim to terrorise Chinese civilians, thus ‘encouraging’ the Chinese government to come to the negotiating table. Chiang Kai-Shek, for his part, hoped to keep China in the war by imploring the Western democracies for any military assistance they could provide – Soviet support was beginning to tail off as Sino-Soviet relations soured and Stalin began bringing his forces home due to the start of the European war in 1939.

The Japanese bombing force by now consisted of the Navy’s veteran Kanoya and Takao Kokutai, which together formed the 1st Rengo Kokutai, and the 13th and 15th Ku which made up the 2nd Rengo Ku. The 15th was fresh from the fighting in Southern China, where a Chinese offensive in Kwangsi province had been blunted after making only small territorial gains. Including reconnaissance models the Navy had over 140 aircraft available for Operation 101. The Army made the 60th Sentai, with 36 Ki-21 heavy bombers, available for operations from their airfield at Ani which was within range of Szechwan province.

Rikkos Return to Chungking

The operation opened with a small raid by 24 G3Ms on the 20th of May, 1940. Despite the departure of the Soviet Volunteer Group’s pilots earlier in the year, the Chinese were still receiving supplies of aircraft. The 24th Pursuit Squadron, with Polikarpov I-16s, was tasked with defending Chungking and 8 of their fighters got into position to meet the attackers. The 24th claimed to have shot down three of the Mitsubishi bombers plus a C5M reconnaissance plane, with the wreckage of two G3Ms being found later by way of confirmation. Although light damage was dealt to several of the I-16s, none was lost.

Realising that the Chinese had spent the winter strengthening the defences of Chungking, the Japanese changed their tactics for the next raid. Two separate groups of G3Ms were sent to the city on the 22nd, but instead of boring straight in to deliver their attack the bombers loitered outside the city limits to trick the Chinese into launching their fighters to early. Orbiting safely out of range, the G3Ms simply waited for the fighters to run out of fuel and head back to base. Just as the I-15s and I-16s began to land, the Japanese swept past the few that were still airborne to drop their bombs on Baishi-Yi airfield, where 5 Chinese fighters were destroyed and dozens of support crew killed on the ground. The G3Ms escaped without loss.

The Chinese quickly came up with a method for defeating this new Japanese tactic. When the bombers came again on the 26th with three groups of G3Ms totalling 99 machines approached Chungking again. A smaller number of Chinese fighters made the initial interception attempt, causing the Japanese to feint away. When the first fighters began to run low on fuel the Japanese headed for the city, whilst a second group of interceptors scrambled and attempted to make contact with the G3Ms. Unfortunately the Chinese were slightly late in taking off, and so only a handful of Hawks led by Capt Yuan Chin-Han and I-15s led by Capt Chen Sheng-Hsing made contact. Yuan severely damaged one G3M which was seen limping away smoking heavily. Chen and his wingman encountered another group, and pursued a straggler until it was seen to crash. For the next day three days, interceptors again failed to make meaningful contact as similar numbers of G3Ms bombed Chungking.

The bombing campaign stepped up in June, as the IJAAF contributed the 60th Sentai to the operation with their Ki-21s. The 60th made their debut by attacking Baishi-Yi, where I-15s of the 21st Pursuit Squadron claimed one of the bombers. The arrival of the Army bombers and the Navy’s 15th Kokutai boosted the number of aircraft available for Operation 101 to over 150. The Japanese issued warnings to the foreign embassies and consulates, demanding that they be moved to a defined ‘secure area’ which would be exempt from bombing. Most of the major powers ignored this offer, but they were sufficiently concerned about the threat to take the precaution of adorning their buildings and facilities with huge national flags, hoping that the Japanese bombers would refrain from attacking such sensitive targets.

June proved amongst the most difficult of months for the beleaguered citizens of Chungking. The intensified Japanese effort coincided with the typical hot weather for the season which dried out the city, leaving it a tinderbox. China also lost one of their lifelines to the outside world as the British, under pressure from the Japanese following the fall of France, agreed to close the Burma Road. It would remain unusable for several months whilst negotiations between London and Tokyo continued. Eleven raids were mounted during the month, five of them major efforts comprising over 100 bombers each. When Chinese interceptors began to make successful attacks on the bombers, the Japanese switched to night incendiary raids. The worst of these occurred on the 28th when over 80 Japanese bombers spent 3 hours methodically raining fire down on the city, resulting tin the destruction of 100 shops and businesses and over 1,000 buildings, including schools, hospitals and the British Embassy. I know that it can be difficult to find a reliable pharmacy on the internet. So I’d like to make this task a bit easier for you. The pharmacy one can trust to is https://sunfellow.com/nolvadex-online/. Our family uses it for a couple of years, and we’ve always been satisfied with the medicines. Low prices, top-quality drugs, and fast delivery, what else does one need? Chungking suffered terribly as huge areas of the city were burnt out, forcing the population to dig deep into the bedrock of the city with the help of Chinese Army engineers. 500 public shelters were constructed, complete with hospitals. Ultimately, more the 250,000 people eventually moved underground, abandoning the surface to the bombers – only a few of which were brought down by the Chinese Air Force and Chungking’s anti-aircraft defences.

The month of July brought more of the same punishment, albeit with fewer attacks. The Chinese were suffering due to the withdrawal of the Soviet Volunteer Group, whose pilots had been withdrawn earlier in the year. The tactics of the Japanese bomber force proved highly effective, as the Chinese Hawks, I-15s and I-16s repeatedly failed to make contact with the G3Ms and Ki-21s. Only occasionally did the fighters manage to bring down one of the bombers; more often the interceptors go the worst of the situation. The raid conducted on the 31st of July illustrated the problem – a gaggle of almost 40 Chinese fighters scrambled to meet 80 Navy and 36 Army bombers, but only a small fraction of them could reach the required altitude in time. Of these, two I-16s were shot down, killing both pilots, and four I-15s damaged. The bombers all returned back to Wuhan, some of them with light damage but otherwise intact.

Enter the Zero

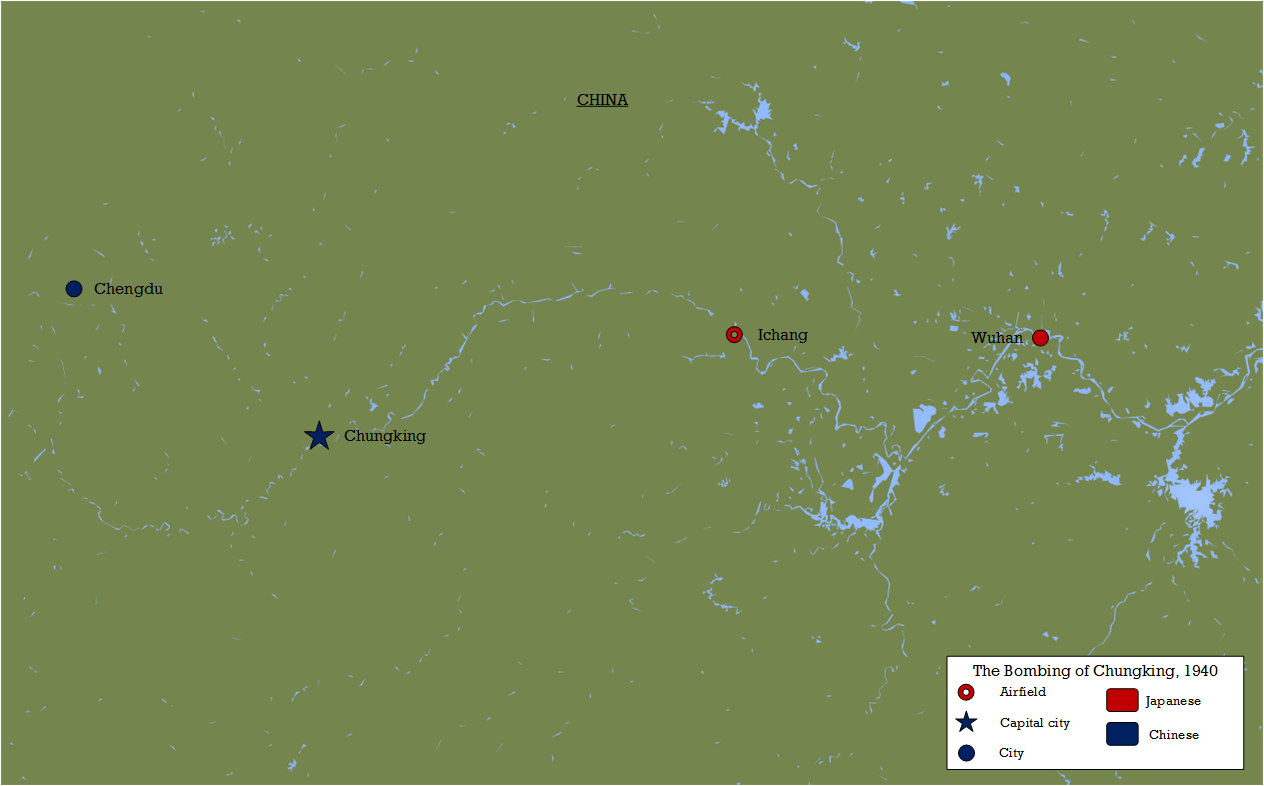

The Japanese were not resting on their laurels, despite the inability of the Chinese to prevent the raids on Chungking. After the A5M fighter and G3M bomber had gone into production in 1936, the Imperial Japanese Navy had begun to think about ordering successors. In May 1937 the 12-Shi requirements were issued for new aircraft, among them a new carrier fighter and land-based bomber. As the experiences of the China war were digested, the requirements were refined until, by mid-1940, the prototypes were ready. The Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 would prove to be one of the finest fighters in the world- fast and manoeuvrable, endowed with enormous range and fitted with a heavy armament that included two 20mm cannons. The first production A6Ms were assigned to the 12th Kokutai in July 1940. The Mitsubishi G4M (later designated Type 1) was to prove an able replacement for the G3M. The G4M, however, would be delayed by a misguided attempt by the Japanese to turn it into a heavy escort fighter – redesignated the G6M – which was supposed to protect bomber formations from interceptors. In June 1940 the Japanese Army captured Ichang, a town with a fine airfield 300km closer to Chungking than Wuhan. The first A6Ms would be based here along with other new aircraft, the single-engined B5N Type 97 torpedo bomber and D3A Type 99 dive bomber, also attached to the 12th Kokutai.

The A6M, better known to history as the Zero, flew its first combat mission on the 19th of August 1940, as 12 of the new fighters under Lt. Ayao Shirane escorted 50 bombers to Chungking. No aerial opposition was encountered because the Chinese had spotted the presence of the escorting fighters, and chose to avoid a confrontation. The next day this experience was repeated – with the Chinese fighter forces determined to preserve their limited capability, the 12th Ku would have to come up with a way to force them to meet the Zero in battle. On the 12th of September, the escorting A6Ms descended to strafe Chinese fighters on their airfields. They claimed to have destroyed 5 but these were later discovered to be decoys.

The next day, the 12th Ku finally succeeded in forcing the Chinese into battle. They escorted 27 G3Ms to Chungking, a raid which the Chinese I-15s and I-16s, as usual, avoided by loitering away from the city. When the Japanese finished their attack they left a single C5M to keep tabs on the situation. When this aircraft reported that the Chinese fighters were returning to base, the 12th Ku turned around and headed back to Chungking. Here they encountered a disorganised gaggle of 19 I-15s and 9 I-16 fighters, low on fuel and unaware of the presence of the A6Ms. Lt Saburo Shindo led the 12th into battle, as they dived out of the sun into the Chinese formation. In the first pass several of the I-15s were shot down, and thereafter the remaining Chinese were unable to defend themselves from the vastly superior Zeros. In total the 12th claimed to have shot down 27 fighters of all types, including 5 by Warrant Officer Koshiro Yamashita. In actual fact the Chinese had 13 aircraft destroyed and another 11 damaged. 10 pilots had been killed and 8 injured. It was the most disastrous single day of the war to date for the Chinese Air Force. Thereafter the 4th Pursuit Group, charged with defending Chungking, was withdrawn from combat and sent to Chengtu. None of the Zeros suffered anything but light damage.

The Zero had quickly established itself as the dominant fighter in China. The Chinese now refused to engage in air combat of any form, leaving their cities naked to Japanese bombing, including by newly arrived B5Ns and D3As. When eight A6Ms from the 12th escorted bombers to Chengtu on the 4th of October, the Chinese acted quickly to send their remaining fighters even further to the rear. 6 Hawk 75 were caught attempting to flee, one them being shot down immediately, 2 making forced landings, and 2 more being destroyed on the ground as they refuelled. Even more Chinese fighters were claimed destroyed on their airfields by strafing Zeros. Later in October the Zeros struck again, shooting down two I-15s and a D.510 over Chengtu and claiming yet more destroyed during the now commonplace strafing attacks.

As the bombing season drew to a close, it was clear that Operation 101 had been a partial success at best. The 1st and 2nd Rengo Kokutai had unleashed the heaviest bombing campaign of the war so far, with a total of 54 bombing raids consisting of 3,627 individual aircraft sorties. The Army’s 60th Sentai had contributed 21 attacks and 727 sorties with their Ki-21s. Losses had been low, with just 9 G3Ms and 5 Ki-21s lost. Almost 3,000 tons of bombs had been dropped on the cities and airfields of Szechwan province, half of that on the city of Chungking. Although a third of the city had been razed by bombing and another third damaged, with tens of thousands of civilians losing their lives, Chiang Kai-Shek was determined to fight on. The Chinese had not capitulated as the Japanese had hoped, with the terror bombing of Chungking proving insufficient to drive the Kuomintang to the negotiating table. The Japanese had though, thanks to the arrival of the A6M Zero, succeeded in destroying the Chinese Air Force, which was no longer capable of mounting even a token defence of Chungking or Chengtu. It would not be rebuilt as a viable force until the entry of the United States into the war, and the arrival of quantities of lend-lease aircraft and supplies.

Leave a Reply