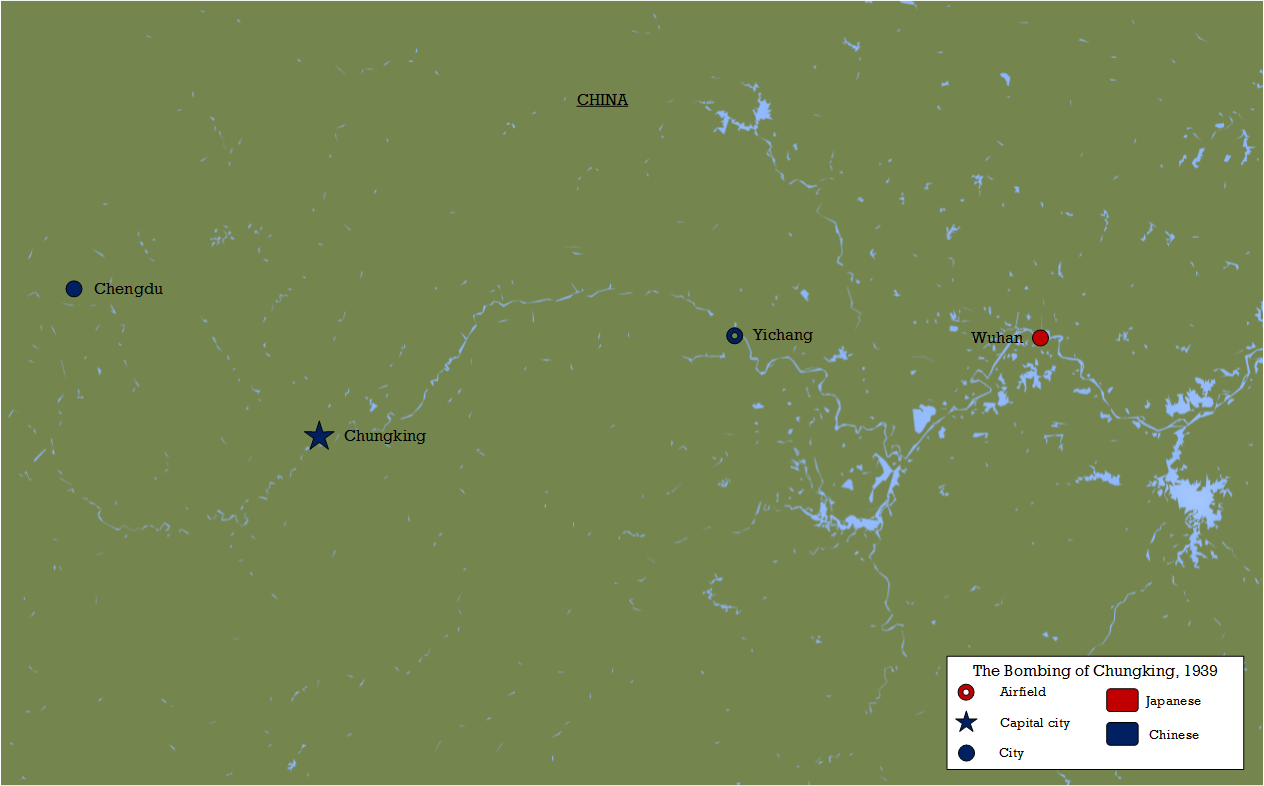

The tri-city of Wuhan fell to the Japanese invaders in October 1938. The invaders, believing that the Chinese would capitulate with the fall of their temporary capital, were surprised to see Chiang Kai-Shek and the rest of the Kuomintang government withdraw to Chungking. This city, in Szechwan province on the confluence of the Yangtze and Jialing rivers, was 500 miles further inland than Wuhan and effectively out of reach of Japanese land forces. Therefore, it was left to the air forces of the Army and Navy to destroy the Chinese will to resist. The bombing of Chungking and other inland cities would prove to be one of the most controversial aspects of the Sino-Japanese War, as thousands of civilians paid the price for China’s resistance.

Army Bombers to the Fore

The Navy bomber forced, now consisting of the 13th Kokutai with 36 G3Ms, was joined by the Army’s equivalent units. The 60th Sentai, with the first production Mitsubishi Ki-21s, arrived in November closely followed by the 12th and 98th Sentai with their Italian-made Fiat BR.20s. The bombers were supported by the Ki-15 command reconnaissance planes of the 18th Independent Chutai, which carried out recce and weather report missions as well as pre- and post-strike analysis of the targets. Two Sentai of short-ranged Ki-27 fighters were available for local air defense and very limited escort duties. The Army was concerned about the state of their bomber crews, very few of whom were capable of operating their aircraft at night, nor had they been trained to co-ordinate with the Ki-15 unit during operations. Spare parts and replacement aircraft were also hard to come by as the supply routes by ship up the Yangtze River to air bases around Wuhan had not been established.

After several weeks of preparation at the Hankow air base, the Army bomber force was ready to launch their first attack on Chungking on the 26th of December, 1938. Further attacks followed in the New Year on the 7th, 10th and 25th January. Although Ki-27s could escort the bombers partway to the target, they lacked the full capacity to follow the bombers all the way to the target. Therefore, over the city, the bombers were open to attacks from Chinese fighters. It became painfully evident that the Ki-21s and BR.20s, like the original model G3Ms, were woefully under-armed in terms of defensive machine guns, but luckily the Chinese fighter force was disorganised and lacking morale following the fall of Wuhan and did not press their attacks effectively. The attackers also encountered Chungking’s notoriously poor winter weather, as heavy overcast made it very difficult to find the targets and deliver bombs onto them effectively – only the attack made on the 10th of January had good weather, with results consequently being reported as ‘satisfactory’.

With this preliminary bombardment completed, the Army bombers moved back to their more permanent base in Northern China. The ‘Red Route’ that was the main supply conduit for Soviet fighters was still active, with an estimated 100 fighters being based in or passing through the city of Lanzhou. This city became the primary target for the Ki-21s and BR.20s during February 1939. Lanzhou was defended by the 17th Pursuit Squadron, with I-15s, and Soviet Volunteers led by Stepan Suprun with I-16s. These fighters rose to intercept 30 Army bombers as they made an attack on the 12th of February. The majority of the BR.20s were forced to abort the mission before they reached the target due to lack of fuel, leaving the remaining Ki-21s to face the Chinese alone. It seems that several of the bombers were shot down, an early demonstration of what was to follow. A second raid was organised for the 20th. This time most of the bombers made it to Lanzhou, in three distinct groups. The first wave in particular suffered from the Chinese interceptors, with the leader being shot down in flames quickly followed by 3 more bombers. At least one aircraft from the third wave was also destroyed, as the defenders claimed to have shot down 9 in total.

On the 23rd of February the Japanese tried again, with a force of 57 bombers in total. The Fiats again suffered from lack of fuel and many had to turn back, leaving around 20 bombers to make the final attack. The Chinese again made effective attacks, claiming to have shot down another 6 bombers around Lanzhou. These severe losses caused the Army to suspend attacks, and re-evaluate the situation. It was obvious that the BR.20s were not up to the task of attacking well defending targets, whilst the Ki-21 needed to be re-designed with extra defensive guns before it could be trusted with long-range, unescorted bombing missions. The bomber force was withdrawn from combat so that it could be re-equipped and re-trained before being sent back to Wuhan. That left the Navy G3Ms of the 13th Kokutai to carry the weight of attacks during the summer. My mom is obese. She is too heavy to do any sports, and what’s worse, she doesn’t want to do anything. She eats all the time and doesn’t want to hear about a diet. A couple of weeks ago, I bought her https://www.disvulture.com/order-phentermine/ tablets. She agreed to take them. I’m not sure how much weight is gone, but she looks slimmer and eats less. Hope the drug will change her attitude to food. The 13th was enlarged, eventually reaching an authorised strength of 36 aircraft, double the number of bombers assigned the earlier units. Like the Army, though, the Navy lacked a fighter with sufficient range to escort the bombers all the way to the targets so the G3Ms would be exposed to Chinese interceptors. The scheme to bomb the cities of western China into submission during the summer was dubbed ‘Operation 100’.

Navy G3Ms to Chungking

The 13th Ku went into action with a pair of raids on the 3rd and 4th of May, 1939. With the Japanese having failed to force Chiang Kai-Shek to the negotiating table by military conquest, the raids were designed to force an end to the China Incident by terrorising the population of the new capital. The G3Ms were therefore loaded with incendiary bombs. Chungking was a densely populated city, swollen with refugees from eastern China, with most of the civilians residing in a spit of land bounded by the Yangtze and Jialing rivers – an area easily identifiable from the air. It was here that the bombs fell on the 3rd, causing huge destruction and starting many fires. Civilian casualties were heavy, with several hundred civilians losing their lives to the bombers – including dozens on board a river ferry which was capsized by a near miss. Chinese I-15s attempted to intercept and claimed to have shot down 7 of the G3Ms, but the day had clearly been carried by the Japanese. The next day the bombers returned at dusk, in order to avoid the I-15s, and delivered another rain of fire on Chungking. Hundreds more were to perish, some as they attempted to climb the city walls to escape the flames.

These raids set the tone for the summer months. The G3Ms attack at dusk or at night in order to avoid Chinese fighters, abandoning any pretence of attempting to hit military targets in favour of city bombing – discovering that the latter were far easier to find and bomb in the hours of darkness. The raids did have an impact on Chinese industry, with many workshops and factories being damaged or destroyed in the raids, and productivity and output did drop as a result. The most obvious impact however was on the civilian population, with thousands of non-combatants being burned to death or severely injured during the campaign. A raid on the 12th of May claimed another 300 lives, and yet more followed on the 25th.

The Chinese proved relatively impotent in the face of Japanese attacks. These were the days before radar, so the air defence network relied on civilians to phone or radio in with news of impending attacks – an imprecise science at best. A handful of ‘sound detectors’ around Chungking could increase the visual detection of raids by a few miles. The Chinese Air Force had been badly battered during the fighting over Wuhan and had not recovered its strength. Few I-15s were available and even fewer could be operated at night, due to a lack of pilots skilled enough in the art of nightfighting. Newer model G3Ms were also better armed than the early types with additional defensive gun turrets, an advantage multiplied by the new practice of operating aircraft in large formations of up to 36 machines. Consequently the loss rate amongst G3M crews was lower than during the disastrous early months of the war. The additional defensive capabilities of the G3Ms were demonstrated on the 11th July, as 8 I-15s attempted to interfere with a raid by 27 13th Ku bombers. One I-15 was shot down in flames and another badly damaged, without loss to the attackers. Another I-15 was lost during an interception on the night of the 4th of August.

One solution appeared to be the acquisition of more capable fighter aircraft to supplement the limited numbers of truly first-rate I-16s. Among the new types imported by the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO) were American Hawk 75Ms, export versions of the P-36 Hawk monoplane, and French D.510 fighters. The latter were armed with a 20mm cannon which greatly increased the chances of destroying enemy bombers. The new machines came into service during the autumn of 1939, as the bombing raids began to tail off due to the increasingly poor weather. Moreover, the Chinese bomber force, encouraged by the arrival of new Soviet DB-3 bombers, regained some of its former aggressiveness. On the 3rd of October, a force of 9 DB-3s set out to attack the Japanese bomber airfield at Hankow. They arrived during an inspection visit by senior officers, several of whom were killed as the bombers conducted an effective attack, claiming more than 50 aircraft destroyed on the ground. On the 4th of October D.510s were scrambled to intercept a huge formation of G3Ms, sent to avenge the attack of the previous day. Engine problems amongst the fighter force and evasive tactics by the Japanese meant that there was no aerial combat that day, and the bombing was again deadly to the Chinese civilians. DB-3s attacked Hankow again on the 14th of October, claiming more Japanese aircraft destroyed in the ground.

By this time the Kanoya and Kisarazu Kokutai had returned to China to join the 13th after an absence of more than a year, swelling the G3M ranks to a total of 72 aircraft. The Army bombers corps, returning to frontline action after having spent the previous few months bombing minor secondary targets, was also ready to try again. The 60th Sentai was enlarged and the best crews from other units were transferred into it. The Navy hatched a plan, ‘Operation Ta-Go’, to attack Lanzhou with the combined bomber force in order to destroy the fighter forces still in the area. Attacks on Lanzhou were mounted on the 26th, 27th and 28th of October, with 20 enemy aircraft claimed destroyed and severe damage believed to have been inflicted on Chinese airfields in the area. In actual fact the bulk of the Chinese air forces in the area had been able to escape the raids, which were consequently much less effective than had been hoped.

Operation 100 Concludes

To round out 1939 before the winter weather closed in on Chungking, the entire Navy bomber force was sent out to attack Chengdu, 200 miles further to the west of the capital, on the 5th of November. The attack was led by Captain Kikushi Okuda, commander of the 13th, who was nicknamed the ‘King of the Bombers’. This time, the Chinese were able to get their fighters into position to defend their city from the attackers. The 17th and 27th Pursuit Squadrons, equipped with D.510s and I-15s respectively, had sufficient warning to climb to altitude and position themselves above the oncoming bombers. Captain Shen Tse-Liu, commanding the 17th, led his French fighters in a diving attack that concentrated on the lead bomber. Okuda’s G3M was hit in the wing root by 20mm fire, immediately catching fire. The fire spread until the wing structure failed, and the bomber nosed over into a terminal dive, with none of the crew surviving the subsequent crash. Two more Chinese squadrons then joined the fray, in total managing to shoot down another three G3Ms before they made their escape.

Thus ended the first sustained civilian bombing campaign of the China war. Although both Army and Navy bombers had been improved to deal with the threat of Chinese interceptors, both the G3M and the Ki-21 still proved to be overly vulnerable to enemy fire. With no Japanese fighters able to make the distance from Hankow to Chungking, this meant that the bombers would continue to sustain losses until the escort problem could be solved. With that in mind, the Japanese would make efforts to secure new forward bases and introduce a revolutionary new fighter as 1940 dawned.

Leave a Reply