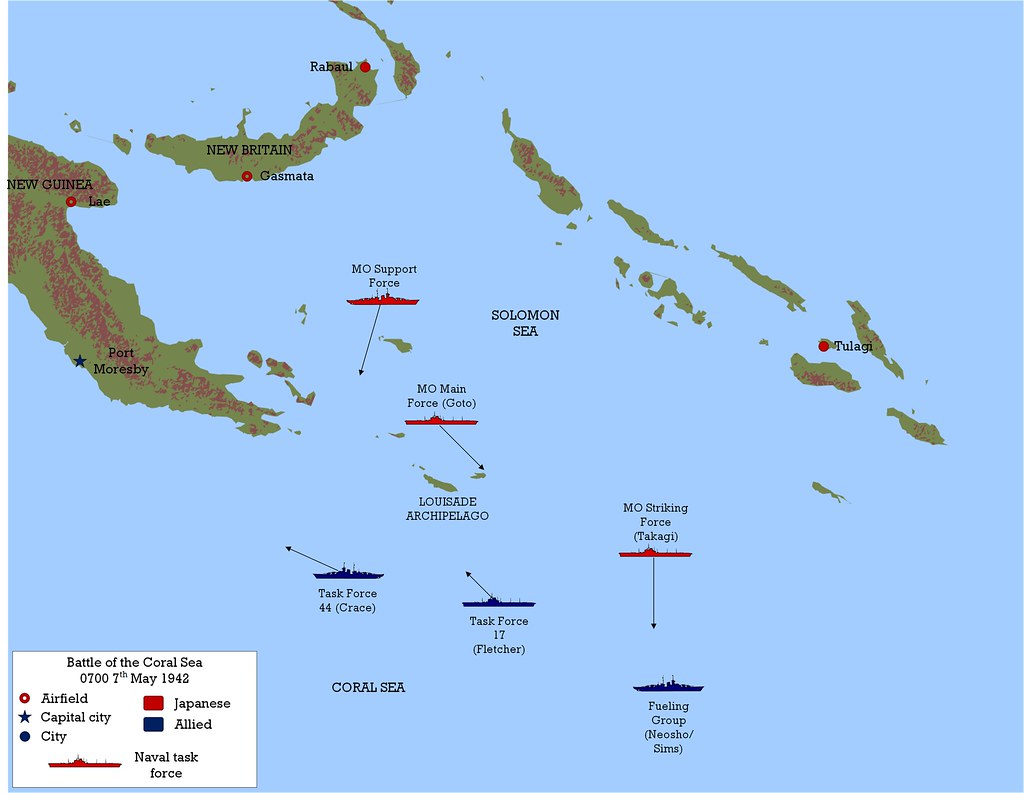

Having completed his attack on Tulagi, Admiral Fletcher spent most of the 5th of May organising his forces and refuelling his ships, prior to the expected confrontation with the Japanese. His carriers, Yorktown and Lexington, were combined into one large Task Force 17 under his direct control. Fletcher received intelligence from Pearl Harbor estimating that the Port Moresby invasion convoy would arrive off the town on or around the 10th May, and that at least two and probably three Japanese carriers would be in close support, launching strikes 2-3 days before the landings. He therefore decided to position his carriers to the southeast of the Louisades, a small archipelago off the eastern tip of New Guinea, a position from which he could intercept both the strike carriers and the invasion fleet. Fletcher resolved to spend the rest of the 6th of May completing the refuelling off his ships, with the intention of launching strikes on the 7th to blunt the Operation MO offensive.

On the 6th a snooping H6K from the Yokohama Ku, operating from Tulagi, spotted Task Force 17. Combat air patrol fighters, after being vectored out to intercept a radar contact, failed to find the flying boat in heavy cloud, and it was able to maintain contact for around 4 hours. At this point the Japanese carriers, commanded by VAdm Takeo Takagi, had entered the Coral Sea having passed east of Tulagi and were around 300 miles north of the Americans, completing their own refuelling. They did not receive the snooper’s reports and believed Fletcher was much further south than his actual position. Actually, as night fell on the 6th the two task forces were, at one point, just 70 miles apart.

Having completed refuelling, Fletcher sent the oiler Neosho, escorted by the destroyer Sims, south to await further developments from a supposedly safe location. He also detached a force of cruisers, on loan from General MacArthur’s forces based in Australia, to cover the likely route to Port Moresby. This “Support Group” was under the British Admiral John G. Crace, and would attempt to stop the invasion in the event that the Japanese sank or disabled Fletcher’s carriers. Task Force 17 would meanwhile wait south of the Louisades for the invasion flotilla. The Japanese MO Striking Force under Takagi was meanwhile heading south, expecting that TF17 was well to the east (over 300 miles) of its actual position. A future post will detail its actions on the 7th.

Searching for the Enemy

As dawn broke on the 7th of May, both the Japanese and Americans expected to see considerable action. Consequently the skies were soon filled with search planes. The MO Main Force under RAdm Aritomo Goto, with the light carrier Shoho (often misidentified as the “Ryukaku” by American intelligence), was operating northeast of Misima Island to provide close escort to the MO Invasion Force. Several of the cruisers of the Main Force launched scouts, with a quartet of old E7K Type 94 searching to the southeast. The seaplane tender Kamikawa Maru, temporarily based out of Deboyne Island in the Louisades, sent out several E8N floatplanes to cover the same area; the Yokohama Kokutai sent 4 H6Ks out from Tulagi; and three of the 4th Ku’s G4Ms headed out from Rabaul. A floatplane spotted Crace’s cruiser force, in position to block the Jomard Passage, at 0810. 10 minutes later a Furutaka E7K reported the sighting of a carrier and escorts, and shortly afterwards Goto learned that the Striking Force was mounting an attack on the same American carriers – however it would soon become clear that a grave mistake had been made.

Fletcher for his part had also sent out scouts, with ten VB-5 SBDs sent out to search to the northwest of TF17. These soon ran into heavy cloud which forced one SBD to turn back short of its allotted radius, but others went out to 250 miles. Lexington’s fighter direction officer attempted to vector his fighters onto radar contacts representing suspected Japanese snoopers, but these proved elusive and none were sighted. At 0735, two Japanese cruisers were reported by VB-5. These were the Furutaka and Kinugasa, north of Misima Island. At 0815 came an electrifying report from another SBD of two carriers and four cruisers. Believing this was the Striking Force on its way to Port Moresby, Fletcher decided to commit his entire strike force, then arrayed on deck, to this target. He issued attack orders at 0915, with the launch commencing about half an hour later.

Yorktown and Lexington between them launched a total of 93 aircraft: 53 SBD Dauntlesses, 22 TBD Devastators and just 18 F4F Wildcats. The bombers set out in four main groups, each with a small number of Wildcats in attendance. The Lexington Air Group led the way, with the Yorktown Air Group following about 15 minutes behind. On completing her launch, the Yorktown landed the morning’s search and learned from the pilot who had reported the ‘two carriers’ that a mistake had been made. He had meant to transmit a message reporting two cruisers, but had made a mistake enciphering this message. Fletcher was deciding whether or not to recall the strike when he received more intelligence: 40th Reconnaissance Squadron B-17s from Australia had spotted both the invasion transports and the Main Force, including the Shoho, and quickly sent out a sighting report. The reported position of the carrier was only 30 miles from the erroneous SBD contact, and a radio message soon went out to the Navy pilots, redirecting them.

Carrier Sighted

At around 1050, the Lexington Air Group spotted the Shoho and her escort of four cruisers and a destroyer. Shoho was a small carrier, having been converted from a submarine tender, and carried an equally small air group of 12 fighters and 6 B5N torpedo bombers. She had just launched five fighters as combat air patrol, three A6M Zeros and two older A5M Type 96s. Cdr William Ault, leader of the Lexington flyers, ordered his men to attack. First in would be the SBDs of VS-2, which would bomb with the intention of supressing Japanese anti-aircraft fire. VB-2 would then follow in an attack timed to coincide with that of VT-2’s TBDs in a coordinated attack planned to overwhelm the Shoho’s defences.

Ault himself led a flight of three SBDs in the first attack on the Shoho. All three missed as the carrier entered a radical turn. The main group of VS-2 under LtCdr Robert Dixon circled around to the north to attack with favourable wind conditions, attracting the attention of the two A5Ms in the process. The Japanese harassed the SBDs as they began their dives on the still-turning Shoho, shooting up one of the bombers. VS-2 claimed three hits with 500lb bombs, but it appears none actually struck the carrier. VS-2 climbed and attempted to gain position for second attack with their 100lb wing bombs, but A5Ms intervened and shot down one SBD. Only one Dauntless made a second attack, on one of the escorting cruisers, but no hits were recorded.

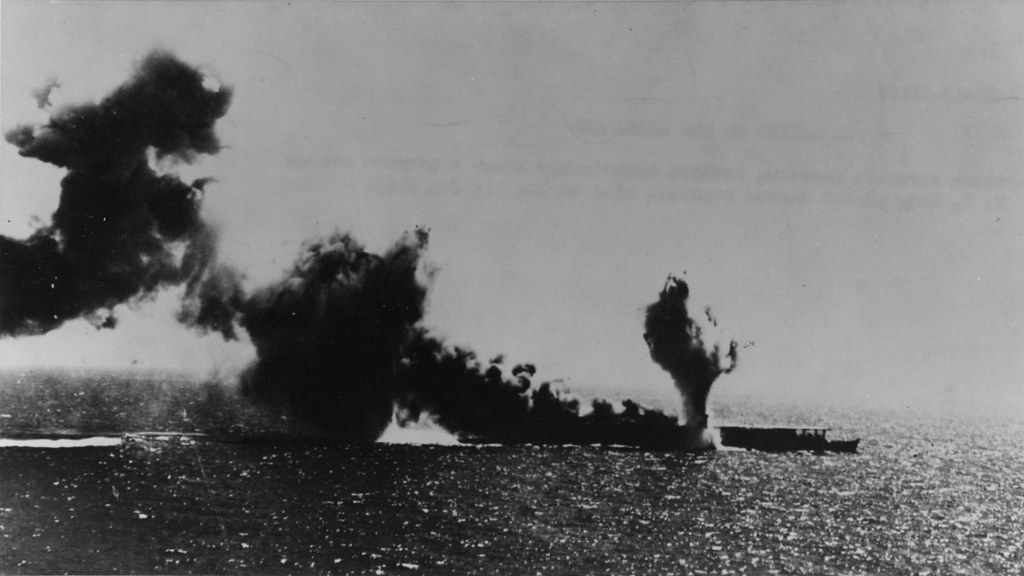

Next in were 15 SBDs from VB-2, lugging large 1,000lb bombs. LtCdr Weldon Hamilton had had to have his main circle near the enemy whilst he waited for the slow TBDs to get into position for the coordinated attack, but at around 1120 the attack began. Fortuitously the manoeuvring Shoho was turning into the wind when VB-2 began their dives, an ideal attack position for the Americans. Again Japanese fighters took pot shots as the SBDs began their dives, but to no avail – each of the bombers made a successful run. Hamilton himself landed a bomb near the Shoho’s aft elevator, and a second hit closer to the bow. Both set of intense fires in the hangars beneath the flight deck and prevent the ship from conducting any further flight operations.

LtCdr James Brett’s VT-2 meanwhile dodged the outlying ring of cruisers before splitting up into two divisions of six in order to deliver a classic ‘anvil’ torpedo attack. The TBDs descended to 100ft, the maximum release altitude for the temperamental Mark 13 torpedo. VT-2 benefitted from the presence of VF-2 Wildcats, which took away the attention of the two airborne A5Ms which threatened the bombers. The TBDs flew a parallel course to the Shoho, a division off each of her beams, before they overhauled the carrier and simultaneously turned in for the attack. The first torpedo was dropped just moments after VB-2 completed their bombing attack. It would turn out to be one of the most perfectly executed torpedo bomber drops of the war: two torpedoes hit on the starboard side, and three on the port side, all along the length of the ship. These tore open the vital engine and machine spaces, and admitted so much water that the carrier immediately lost power and began to list. VT-2 then made good their escape without losing a single plane.

The Shoho, badly flooding and with severe fires, was doomed – but the attack was not over yet. The Yorktown Air Group arrived in time to witness VB-2 and VT-2 cripple the ship, and their own attack would follow hot on the heels of the Lexington’s. LtCdr William Burch, leading the Yorktown’s SBD contingent, spotted that the carrier was heading into the wind and elected not to wait for the slower TBDs of VT-5 to get into position before launching his own attack. VS-5 began their dives five minutes after VB-2 had completed their attack, and a total of fifteen 1,000lb bombs were dropped with no less than nine hits and two near misses claimed. Immediately after them came eight VB-5 SBDs, who claimed a further six hits on the hapless Shoho.

The coup-de-grace came from LtCdr Joe Taylor’s VT-5, finally in position. At 1130 they began their attack on the almost stationary carrier, which was burning fiercely and surrounded by dense smoke. A few of her anti-aircraft guns were still firing when all ten VT-5 TBDs made their drops against the carrier’s starboard side – at least two of the fish hit home, and possibly more amid the confusion. VT-5 likewise escaped without being molested by Japanese fighters.

“Scratch one flat top!”

The various groups of American aircraft were now quite separated, and began to rejoin in mixed formations from the two air groups. VF-42 was called upon to protect their charges from some of the Japanese fighters that were still airborne, and LtCdr James Flatley – a future leader of US Navy fighter theory and tactics – scored his first victory by shooting down an A5M. Two other fighters, probably faster A6Ms, were also claimed to have been shot down by one of his wingmen. One of the Yorktown SBDs became lost, and set out for New Guinea hoping to reach Port Moresby. This aircraft ditched well short of the island, but the crew were later rescued. This loss, and the sole SBD from the Lexington that was shot down, were the only American losses – a fine exchange for the first Japanese carrier sunk during the war.

On his way back south towards the Lexington, LtCdr Dixon sent out a pre-arranged message to confirm the success of the mission – ‘Scratch one flat top. Signed Bob’. However, some of the officers present, including Flatley, made note of the fact that the entire strike effort had been directed against the Shoho, leaving other valuable ships to escape undamaged. In the future an officer in tactical command, or OTC, would coordinate mass carrier strikes consisting of multiple squadrons but it would take time to synthesise the lessons of the Shoho incident, time that was in short supply during the busy summer of 1942.

Leave a Reply