In mid-1941 the USAAF began to build up its strength in the Philippine Islands. The Far East Air Force was to be reinforced so that it could effectively defend the islands from potential Japanese incursions, in defiance of years of established military doctrine that wrote the Philippines off as indefensible. The driving force behind this change in strategy came from General Douglas MacArthur, who was recalled to active duty in the US Army as the commander of the Philippines.

One of the first priorities for the FEAF was to beef up its heavy bomber contingent. The only modern bombers in the archipelago were Douglas B-18 Bolos, which had been considered inadequate aircraft even as they were coming into service. They lacked the range and bomb load to be able to effectively strike shipping at sea, but were nevertheless manufactured in significant numbers due to the lack of an alternative. However, a new bomber then entering squadron service promised to change the situation.

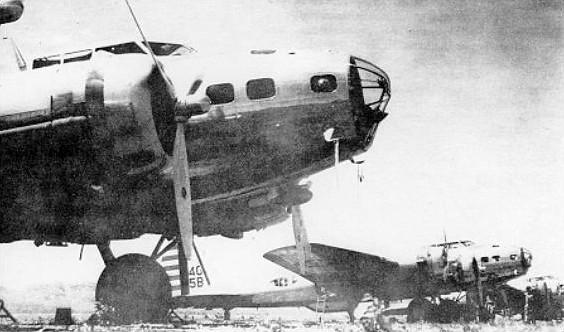

This new aircraft was the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, which had actually lost out in competitive trials to the B-18 when the prototype crashed. However, the design was sufficiently promising for the Army Air Corps to order a number of pre-production models with a view to placing larger orders when various design flaws were corrected. By mid-1941, the B-17 was entering full production and enough were entering service that it was possible to assign several squadrons to overseas stations. Top of the list to receive the big new bomber was the FEAF.

However, getting these aircraft to the Philippines would prove to be a significant challenge. Smaller aircraft were crated up and then sent to the islands by ship, but the facilities to re-assemble aircraft as large as the B-17 simply did not exist in any of the Filipino ports. With 7,000 miles of open ocean separating Manila from San Francisco, even the prodigious fuel capacity of the bomber would be insufficient even to make it halfway across the distance, and intermediate facilities for refuelling stops were limited in number and rudimentary at best. Still, the desire to prove that the heavy bomber could be a truly global weapon no doubt played a role in the USAAF’s eventual decision to send the Flying Fortresses by air.

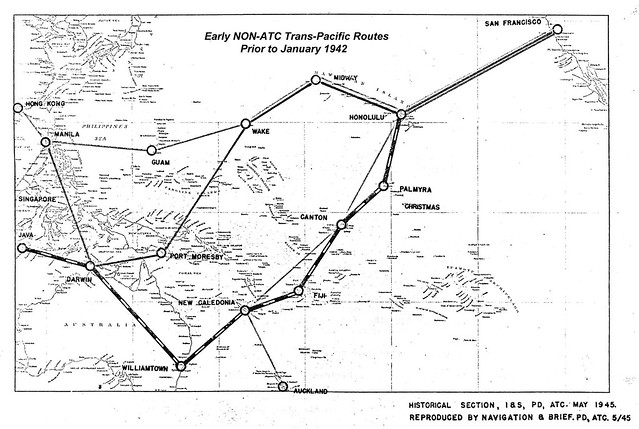

Potential routes for the South Pacific Air Ferry Route were soon mapped out. The natural starting point was Hamilton Field, north of San Francisco. From here B-17s equipped with ferry tanks could just about make the 2,400-mile flight to Hickam Field on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. This was the major USAAF base in the Pacific and had extensive facilities for maintaining large fleets of aircraft. After the crews were rested and their aircraft refuelled, the next stop was Midway Island, a tiny dot 1,100 miles further West that had only been militarised with the construction of a hard-surface runway in 1939. Up to 25 heavy bombers could be handled at the Eastern Island airfield. From Midway, the bombers could make another 1,000-mile flight to Wake Island, which was an even newer base than Midway – its crushed coral airstrip had only been completed in August 1941.

The next leg proved to be the most difficult. The American possession of Guam was the next logical stopping point, laying 1,500 miles west of Wake but, despite having facilities for PanAm flying boats, it had no runways suitable for land-based planes. With the B-17s unable to make the 3,000-mile direct flight from Wake to Manila, another route was needed. Possible stops to the south included the Australian possessions of Rabaul, on New Britain island (1,900 miles), and Port Moresby in New Guinea (2,400 miles). The airfield at Rabaul was too soft to reliably handle the heavy B-17s, and its position in a bowl-like volcanic caldera made approaches difficult. Therefore, the more distant Port Moresby, although primitive, was chosen with Rabaul retained as an emergency landing field.

To reach New Guinea the bombers would have to fly over the Japanese-held mandates, the Marshall and Caroline Islands. These islands had been closed to foreigners, with the only recent visitors being German auxiliary cruisers. Intelligence on the presence of warships, fighter aircraft and early warning systems was non-existent, so to minimise the potential threat to the passing bombers it was decided that they would make the passage at night, flying at high altitude, with all lights extinguished. These flights, at 26,000ft, would require the crews to be on oxygen as they passed over the mandates.

From Port Moresby it was a relatively short 900-mile flight to Darwin, in Australia’s Northern Territories. The airfield here was often obscured by dust, but it was nevertheless suitable to host B-17s. The final leg covered the 2,000-mile flight from Darwin north to Clark Field, on Luzon in the Philippines. The airfields in the south lacked many of the facilities required by B-17s. USAF officers were flown by Navy PBY Catalinas to each station in order to coordinate the preparations for the flights. Spare parts for the engines and other critical components were unavailable, and there were no local supplies of the 100-octane aviation gasoline that the four Wright R-1820 engines on each bomber required.

The 19th Bombardment Group was selected as first heavy bomber group to be sent to the Philippines. Its 14th Bombardment Squadron, which was already in Hawaii having recently made the first nonstop flight from the continental US to Oahu, would be the first formation to make the flight with 9 B-17C and B-17D models. They departed from Hickam on the 5th of September 1941, stopping overnight on Midway before arriving at Wake (having lost a day by crossing the International Date Line) in order to cross the mandates at night. With just a few hours rest the B-17s took off at 11pm, although one of the bombers turned back to have an engine problem repaired before catching up with the others at Port Moresby. Another aircraft lost an engine over New Guinea, but elected to fly on the Port Moresby rather than divert to Rabaul. All nine planes arrived safely without arousing the Japanese. The 9th was reserved as a rest day, so the group departed for Darwin on the 10th after topping up with inferior 90-octane fuel. Early on the 12th the squadron set off on the last leg to Clark Field, only to be told that the airfield was closed due to weather and that they should divert to Del Monte – a new and secretly constructed bomber field on Mindanao. Major Emmett O’Donnell, commander of the 4th, decided to push on regardless and the B-17s had to make several approaches in bad conditions before they all landed safely by 4pm, having finally concluded a flight of almost 7,500 miles.

In order to better prepare for the next transit, the USAAF chartered ships to deliver barrels of fuel and small stocks of bombs, ammunition and spare parts in case the B-17s were ever called upon to mount combat missions from the ferry airfields. These paid several calls to the stopover points before the onset of war made the journeys too hazardous.

On the 12th of October two more squadrons of the 19th Bomb Group – the 28th and 30th Bombardment Squadrons – assembled at Hamilton Field in order to begin their voyage to the Philippines. 26 more B-17s would make up this wave, but unlike the relatively straightforward first wave there would be endless problems. Many of the bombers were brand new and had not being fully shaken-down, so there were numerous problems that prevented them being sent across the Pacific in large groups. Consequently the B-17s of this wave ended up scattered across the entire length of the ferry route, with groups at every station from San Francisco to Australia. Major-General Lewis H. Brereton, newly appointed commander of the FEAF and on his way out to the Philippines, happened to come across a group of bombers led by LtCol Gene Eubank at Wake. Eubank’s bombers and Brereton’s PanAm Clipper flight were both detained at Wake for several days as bad weather made flying impossible.

Mechanical problems, bad weather and lack of capacity at the intermediate airfields caused a backlog of bombers that gradually made their way to Clark, with the final aircraft arriving in the Philippines on the 5th of November. Despite all the problems, all 26 B-17s arrived intact, bringing the FEAF up to a total strength of 35 Flying Fortresses. These would comprise the FEAF’s total heavy bomber force during the war, flying several missions before being forced to withdraw to first to Java and then to Australia. Another group, the 7th Bombardment Group, was in the process of transferring to the Philippines when its first echelon was caught up in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The 7th was destined never to reach the Philippines, although it did join the 19th in Australia before being assigned to India in mid-1942.

With the onset of war the South Pacific Air Ferry Route to the Philippines was cut by the Japanese. Guam fell almost immediately, and Wake Island was besieged for two weeks before finally falling on 23rd December 1941. The Japanese offensive also ruled out any prospect of transferring aircraft to the Philippines by ship with the result that a convoy led by the cruiser Pensacola, carrying 52 A-24 dive-bombers of the 27th Bomb Group and 18 P-40s of the 35th Pursuit Group amongst other supplies, was diverted to Brisbane. US engineers were already developing alternative routes via Canton, Fiji, New Caledonia and Brisbane but these were not available until early 1942. The FEAF would have to fight with what it had.

Leave a Reply