The Japanese, keen to press back against the Americans in the Central Pacific as well as keeping up-to-date with developments at Pearl Harbor, planned an audacious mission to conduct a combined bombing/reconnaissance attack on the naval base in March 1942. The mission was designed to put additional pressure on the Americans who were still busy repairing ships and facilities following the attack in December 1941, and give the Japanese a way to get the latest reconnaissance data on the number of ships in Pearl. The Japanese codename for Oahu was AK, and hence the codename for the mission became Operation K.

Three submarine reconnaissance missions had already been flown over Pearl by E14Y floatplanes. These had been conducted on December 16th, January 4th, and February 19th. On each occasion the aircraft had returned unmolested, but the tiny aircraft were unable to carry any meaningful bomb load and had done no damage to the naval base. The Americans had tracked these flights but had been unable to intercept them.

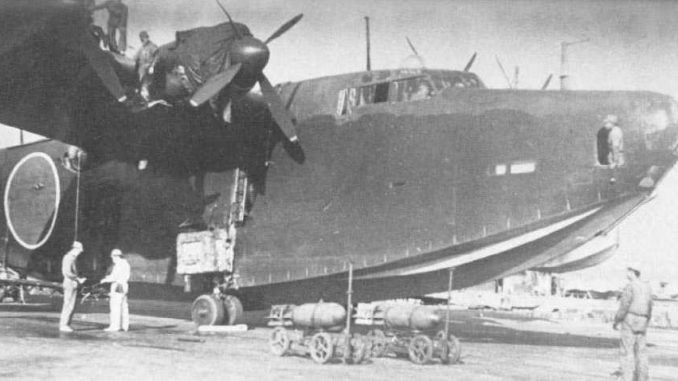

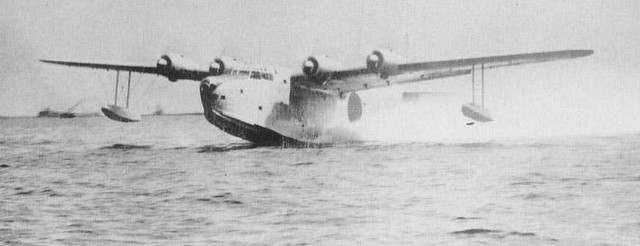

To do meaningful damage to the facilities at Pearl, a more capable combat aircraft was needed. No carriers could be spared for such a risky mission, which meant that land-based aircraft or flying boats would need to be enlisted. Neither the Chitose Kokutai’s G3M bombers nor the 4th Kokutai’s G4Ms had a hope of flying the 4,000-mile round trip from the Marshall Islands to Oahu, and the Yokosuka Kokutai’s H6Ks were likewise incapable of making the trip. However, the Japan-based Yokohama Kokutai – a special unit tasked with evaluating new aircraft – was by February 1942 completing its evaluation of a new patrol bomber, the Kawanishi H8K Type 2, with much longer endurance. The Yokohama Ku provided two pre-production H8Ks for the mission, and these departed from Yokohama on the 15th of February.

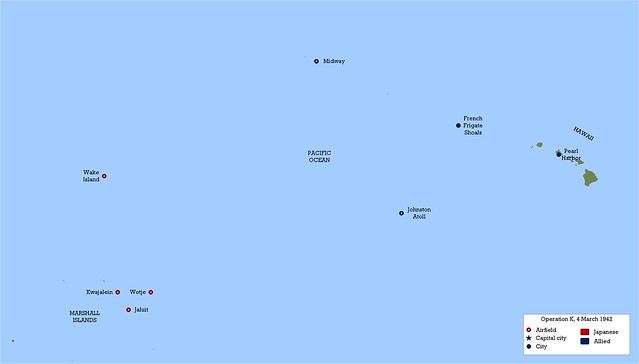

However, even these advanced aircraft lacked the fuel to fly the mission with bombs loaded. To extend their range, the 4th Air Fleet enlisted the help of the 6th Fleet’s submarines. First, the I-22 reconnoitred various locations and discovered that Kanemiloha’i, otherwise known as the French Frigate Shoals, a coral reef 560 miles from Oahu, was ideal as a clandestine refuelling stop. Five other submarines were positioned to assist with the mission. I-15, I-19 and I-26 were all large aircraft carrying submarines with facilities for carrying aviation fuel. All three made their way to the French Frigate Shoals. I-9 was posted between Wotje, the nearest Japanese base to Pearl Harbor, and the refuelling point to provide navigational support. Finally, the I-23 was positioned south of Oahu to provide weather information.

The Japanese had broken the encryption codes for the US Navy’s weather service, but these codes were changed on the 1st of March and this valuable information source was lost. Instead, the mission would have to rely solely on the reports of the I-23. This boat had already seen considerable action, having shelled an oil refinery in California on December 18th, and she had been present at Kwajalein during Halsey’s raid there on the 1st of February. The last report from the I-23 was received on the 24th of February. She was never heard from again, and presumed lost – her fate has never been determined.

Operation K

At Wotje, the two crews prepared for the mission. The two H8Ks were flown by Lt Hisao Hashizume and Ens Shosuke Sasao, and both were personally briefed by Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue, commander of 4th Fleet. Their primary target was the 10-10 dock, a drydock in the Pearl Harbor naval base so-named because it was 1,010ft long. It could dock and repair the largest ships in the Pacific Fleet and was therefore of strategic importance. Its destruction would force any damaged carrier or battleship to retreat to the continental United States for repairs.

Japanese not the only ones to benefit from signals intelligence. The Japanese Navy’s codes had also been broken, and two American stations, codenamed Cast in the Philippines and Hypo in Hawaii, were listening in. Some messages appeared to show a joint operation between the 4th Air Fleet and the 6th Fleet, responsible for submarine operations. Other messages pointed to locations codenamed AH, AFH and AF which were all assumed to be in the Hawaiian chain. The commander of station Cast, Cdr Joseph Rochefort, deduced that an operation involving seaplanes launched from seaplane carriers near Oahu might be in the offing. However, by the time this intelligence had been firmed up, the two bombers were already on their way.

Each H8K was loaded with four 250kg bombs and a full load of fuel. On dawn on March 4th, Wotje time, the two bombers lifted off and began the 1,600-mile, 13-hour leg to French Frigate Shoals. Enroute they crossed the International Date Line and crossed back into March 3rd, before landing and rendezvousing with the three refuelling submarines at 1830. The sea was relatively rough, and the swell caused problems during the refuelling operation. Some of the lines securing the H8Ks to the submarines parted, but the refuelling was nevertheless completed successfully. At midnight, the H8Ks lifted off again for the 560-mile leg to Oahu.

The weather on the 4th of March proved the utility of having accurate data, be that from intercepted sources or from a pre-positioned submarine. As it turned the conditions over Oahu were poor, with heavy clouds and occasional storm showers. However, this proved as much of a benefit to the Japanese as it was a problem, as it made the task of the American air defence teams that much harder. Despite the experience of the December 7th attack, the Americans were still inexperienced in air interception techniques, especially at night. When radar reported two contacts incoming from the northwest, the Hawaiian Air Force sent up just four P-40s to intercept whilst the Navy sent out five torpedo-armed PBYs from PatWing-2 to find the “carrier” that was believed to have launched the intruders.

The Second Pearl Harbor Raid

The two H8Ks arrived at 0200 local time. The interceptors, lacking any sort of radar, untrained in the art of night operations, and lacking sufficient guidance from the ground, failed to find them in the bad weather – a timely rainstorm over Pearl Harbor greatly assisted the Japanese in remaining undetected. However the weather also hampered bombing efforts, as did a very effective blackout which had been instituted since the outbreak of the war.

When Lt Hashizume turned to make his final approach on the target, Ens Sasao failed to notice and the two aircraft commenced their bomb runs independently. Hashizume calculated that he was over the drop point and released his bombs from 15,000ft, however these missed the naval base by almost 6 miles. The four bombs landed in a wooded area on the slope of Tantalus Peak. The explosions smashed windows and caused other minor damage to the Roosevelt High School, which was about half a mile away from the impact point. The bombs caused no meaningful damage and there were no casualties to military personnel or civilians.

Ens Sasao also failed to find the naval base, and instead settled on the idea of using the Ka’ena Point lighthouse as a reference point. He then quickly calculated an approach to Pearl Harbor, and released his bombs at the expected moment. His calculations were way off the mark, and his bombs appear to have landed in the sea near the entrance to the harbour. In fact, the Americans remained unaware that two separate aircraft had dropped bombs until after the war, when the interrogation of Japanese officers revealed Sasao’s actions.

Neither aircraft was able to give an accurate report of the ships in the harbour, although Hashizume claimed to have sighted a carrier. He was mistaken in this claim, because the Pacific Fleet’s flattops were all absent from Pearl Harbour on the 4th – the Enterprise was about to launch her attack on Marcus, the Lexington and Yorktown were operating together in the South Pacific, and the Saratoga was still under repair in the United States following the torpedo damage she sustained in January.

Unable to find each other in the dark, both H8Ks set course for Wotje and flew into the darkness independently. Each pilot faced a 2,000 mile, 15-hour journey on their remaining fuel, with little chance of rescue should a mechanical issue force one of the flying boats down onto the ocean. Hashizume, noting some damage to his aircraft sustained during the takeoff from French Frigate Shoals, elected to fly on to Jaluit where better repair facilities were available. Again crossing the International Date Line both aircraft arrived in the Marshalls safely on the afternoon of March 5th.

The raid had actually achieved very little, and in fact had been very costly for the results. The I-23 was lost with all hands. There were no casualties on the ground, and no damage whatsoever to military facilities – the 10-10 dock had escaped completely unscathed. No useful reconnaissance data had been obtained, partly due to the poor weather conditions. One radio station in Los Angeles, which was still in the grip of a panic that had swept the west coast following the attack on Pearl Harbor, ran a story that incorrectly reported ‘significant casualties’ on the ground. This erroneous report was picked up by Japanese and used as the basis for claims that 30 sailors and civilians had been killed.

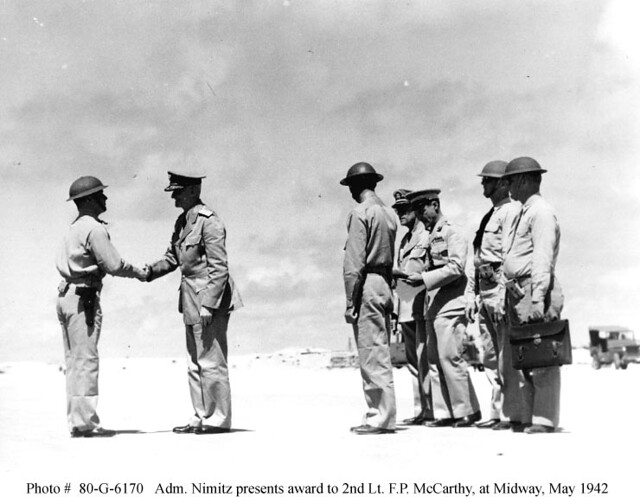

A second operation was planned for the Yokohama pilots shortly after their return. 4th Fleet planned a mission to reconnoitre the American bases at Midway and Johnston Islands, both of which could be reached by unarmed H8Ks without the need to refuel from submarines. The mission began on March 10th, with the same two aircraft participating. Hashizume flew to Midway, where a Marine Corps radar set detected his H8K. Twelve F2A Buffalos from VMF-221 were sent out to intercept, and a division of four led by Capt. James Neefus caught the bomber and shot it down with no surivivors. Sasao safely returned from his mission to Johnston with excellent photographs.

Operation K was to have a significant impact on the course of the war, out of all proportion to its limited scope. Analysis of signals intelligence allowed the Americans to deduce that the attack had originated from the French Frigate Shoals, and as a result a seaplane tender was sent to patrol the area on a permanent basis – an action which would have disastrous consequences for the Japanese during June’s Battle of Midway. When a new Operation K was planned to provide information on the whereabouts of the American carrier fleet, the presence of the seaplane tender Thornton was enough to force the cancellation of the effort. The Japanese therefore had no idea where the American carriers were as the battle was joined.

Excelente artículo, como toda vuestra página. Os leo a menudo y para mí sois una referencia habitual. Gracias!!