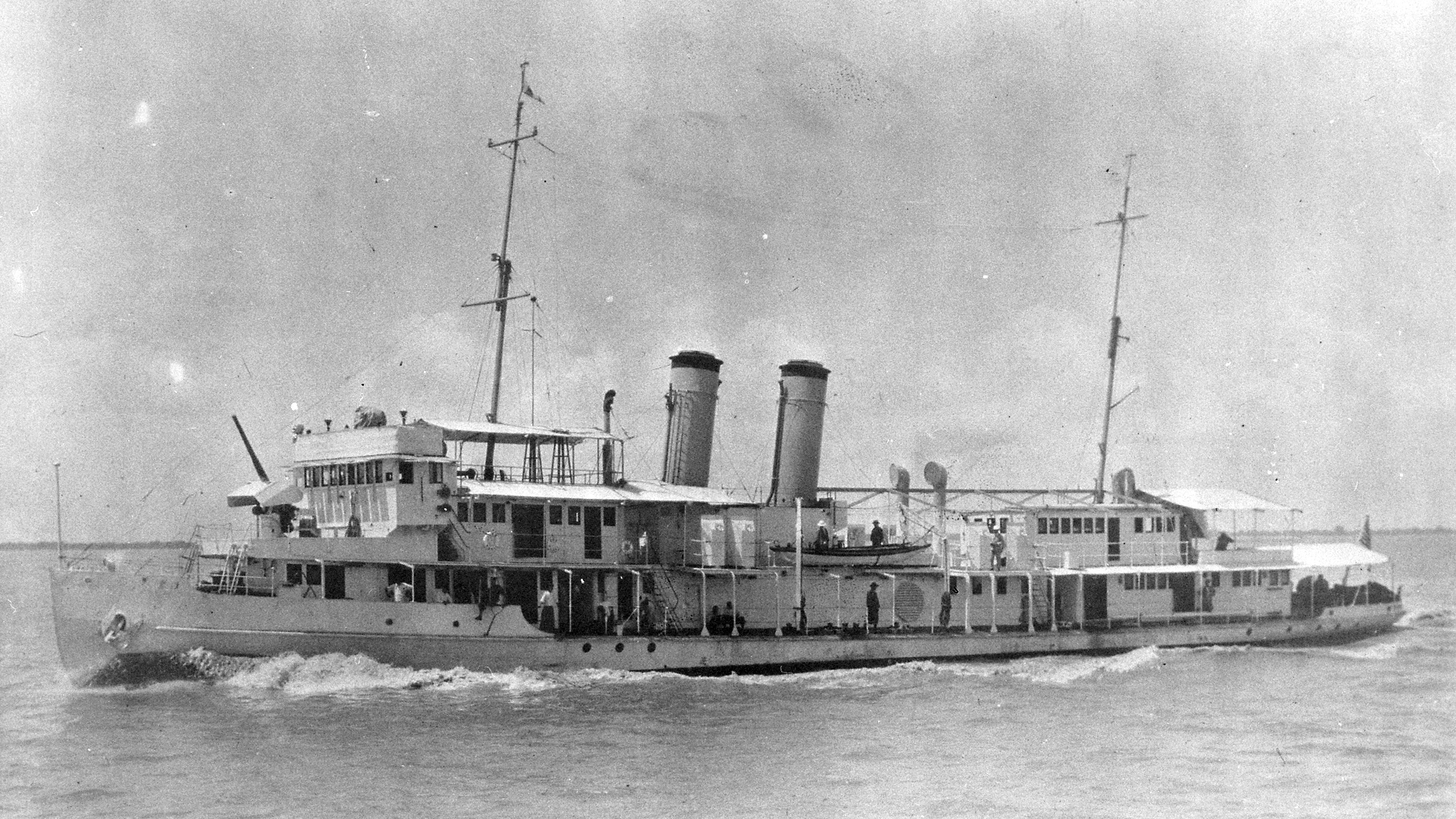

USS Panay was a river gunboat built in Shanghai in 1927-8 for the US Navy’s Yangtze River patrol. She was a small vessel, only around 500 tons displacement, with a shallow draft that allowed her to patrol up and down the Yangtze between the major cities of Hankow, Nanking and Shanghai. Her job, in concert with the 5 other river gunboats of the ‘YangPat’, was partly to protect American civilians from Chinese bandits and warlords who occasionally threatened river traffic. Their main role, however, was to protect the interests of companies like the Standard Oil Corporation by ‘showing the flag’. This latter role helped to enforce the ‘Open Door Policy’, which kept China open to American businesses hoping to trade in the area. Unfortunately having warships so close to an active war zone was an invitation to disaster, as the Panay Incident demonstrated.

In 1937, as the Japanese attacked Shanghai before moving towards Nanking, the vessels of the Yangtze Patrol were instrumental in helping American civilians move out of the most dangerous areas but ferrying them upriver to safer locations. In this they were joined by craft of other neutral nations, with the British Yangtze River Patrol’s gunboats of the Insect-class also in the area. As the fighting around Nanking, and in particular the attacks by Japanese bombers on the city, began to threaten American lives the gunboats moved in. Most of the neutral civilians, including the US ambassador to China Nelson T. Johnson, were taken upriver to Hankow or Chungking where they would be safe from the fighting, at least temporarily. In early December the Chinese government began to follow, as Chiang Kai-Shek and the rest of his cabinet decamped to Hankow, leaving the old capital to be ravaged by Japanese soldiers in what would become known as the ‘Rape of Nanking’.

A few miles south of Nanking, upriver from the now burning capital, lay the Panay. The gunboat had been moored in Nanking harbour until the 8th of December, when Japanese shells began falling close by. She therefore sailed upriver to the Standard Oil terminal, and informed the Japanese of her new position. Her crew also went to work displaying prominent American flags on her upper works. At the terminal, Panay linked up with three Standard Oil river tankers: Mei Ping, Mei Hsia, and Mei An, each displacing around a thousand tons. The tankers were carrying hundreds of Chinese employees of Standard Oil and their families away from the fighting. The convoy was moored at a small jetty at a location that was hoped to be far enough away to avoid getting caught up in the conflict, but this proved wishful thinking. On the morning of December 12th, artillery rounds began landing in the river within 200 yards of the Panay, so her commanding officer, LtCdr James J. Hughes, made the decision to move his little flotilla further upriver, where they would hopefully be out of range of the Japanese batteries. In addition to her crew the Panay also hosted 15 passengers in all – several embassy staff and a number of newsmen, including newsreel cameraman Norman Alley, who would capture the tragic events of the day on film.

The Cherry Blossom Society

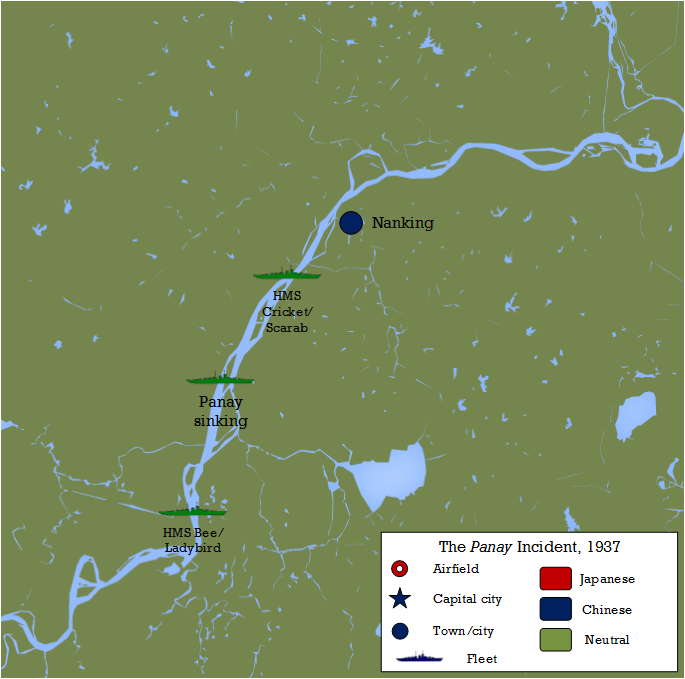

The wisdom of this move was highlighted by an incident later that same morning. An Imperial Japanese Army officer in charge of an artillery unit, Col Kingorō Hashimoto, was the founder of an ultra-nationalist clique within the army – the Cherry Blossom Society – and privately hoped to provoke the British and Americans into joining the war. He ordered his gunners to fire on any vessels passing through the sector, regardless of nationality or status. Two Royal Navy gunboats, HMS Ladybird and HMS Bee, were the first to fall afoul of this renegade. They were escorting a convoy of their own upriver from Nanking, which came under attack at around 9am. Ladybird was hit by half a dozen shells which killed one sailor and injured several others, but did not impede her progress. Bee, coming to the aid of Ladybird, was herself bracketed by shells but did not suffer any damage. Panay and her charges, passing through a nearby stretch of river later that day, were also subject to a brief shelling.

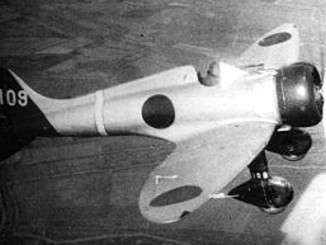

The passage of so many ships up the river prompted the Army to request air support in order to knock the vessels out. Lacking effective air support of their own, army units were obliged to call on the services of the 2nd Rengo Kokutai which had provided support throughout the Shanghai and Nanking operations. A report was passed to the fliers which specified that around 10 ‘enemy troop carriers’ were moving upriver. No mention was made of the fact that the vessels were in fact neutral. Capt. Morihiko Miki, in charge of the 12th Kokutai, was tasked with organising the navy aircraft into a strike mission which would go after the ‘Chinese’ craft. 9 A4N fighters and 6 D1A dive bombers from the 12th Ku were assigned, as were 3 B4Y torpedo bombers and 6 more D1As from the 13th Ku. The aviators, motivated by the promise of decorations for the sinking of these targets and anxious to exercise their anti-shipping skills that had largely gone unused since the previous September, raced each other to the reported location of the enemy.

The Panay convoy, meanwhile, had reached a location that seemed to offer safety from attack by the Japanese. The gunboat and her charges anchored in a wide stretch of the river, and a message was sent to the American embassy specifying their location, with a request that this information be shared with the Japanese. The crew of the Panay began to relax to the extent that a group of sailors was allowed to take a motorboat over to the Mei Ping, which did not observe the US Navy’s rules on the availability of alcohol aboard ship.

The Panay Incident

At 1:37pm, a lookout spotted the first of the Japanese aircraft – these were the B4Ys of the 13th Ku, led by Lt Shigeharu Murata, which had won the race to find the craft. The B4Ys commenced a level bombig attack, which immediately hit home – the Panay’s pilot house was hit by a 60kg bomb which knocked LtCdr Hughes unconscious and broke his femur. This attack also wrecked the gunboat’s forward 3” gun and destroyed the radio room, preventing any SOS messages from being sent. This attack was followed by a dive-bombing by the 13th Ku D1As, which scored several near-misses on the gunboat. An oil line was cut, which prevented the operation of the Panay’s engines and her emergency pumps. Her executive Officer, Lt A.F. Anders (whose son would later orbit the moon during the Apollo 8 mission), was wounded in the throat and struggled to direct damage control parties by hand-writing notes instead of speaking. Meanwhile, Norman Alley captured the events on film.

Not long after the 13th Ku launched their attacks, the 12th Ku A4Ns and D1As arrived. Seeing the Panay already in trouble, they concentrated on the nearby tankers, dropping bombs and strafing. The Mei Ping was hit and a number of fires broke out, but the Panay sailors who had earlier made the trip over to the tanker helped to control the situation. Mei Ping and her sister Mei Hsia eventually secure themselves to a pontoon, whilst the Mei An beached herself to prevent flooding from taking her under. The Japanese then left, noting the fact that none of the vessels appeared to be sinking. The Panay’s gunners had been unable to return any effective fire during the raid because her defensive machine guns were sited to fire at bandits along the riverbank, rather than at aerial threats.

The bombers of the 13th Ku, having returned to base to refuel and re-arm, headed back out to the Yangtze to finish the job. Initially unable to find the Panay convoy, the group of dive bombers lead by Lt Masatake Okumiya searched up and down the river before coming across a convoy of four ships. Diving into the attack, it wasn’t until after bombs had been released that Okumiya realised which ships he was attacking – the large Union Jacks in evidence identified the convoy as British. It was in fact a pair of British gunboats, HMS Scarab and HMS Cricket, escorting a hulk and the SS Whangpoo. Fortunately for the British, all of Okumiya’s bombers missed the mark, and the convoy sailed on upriver without a scratch.

On board the Panay, it was obvious the ship was going down. Whether from the direct hits by the B4Ys or the near misses by the D1As, water was leaking into the hull at a rate too fast for the crew to cope with. The gunboat’s motorboats were used to gradually ferry the crew and passengers to the riverbank, but suffered several strafings from the 12th Ku A4Ns that hovered over the scene. Once safely ashore, and when the Japanese planes had left, the survivors were able to take stock. All of Panay’s officers had been wounded, as had many of the enlisted men. One sailor, storekeeper Charles Ensminger, and an Italian journalist, Sandro Sandri, were killed during the attack, as was the American captain of the Mei Ping, Carl H. Carlson. Another Panay sailor, Coxswain Edgar C. Hulsebus, died of his wounds the night of the attack.

The crew watched from the shore as the Panay slipped under the surface just before 4pm, only two hours after the attack started. Because the gunboat’s radio had been destroyed by the first bomb hit, some of the survivors had to walk to the nearest village to make contact with the US embassy in order to inform them of what had happened. In doing so they hoped to avoid Japanese patrols which, given the events of the day, might not be trusted to respect US neutrality. Eventually though word of the attack reached the American and British authorities, who despatched a relief effort. USS Oahu, a sister of the Panay, and HMS Bee finally arrived 2 days after the attack to take the survivors to Shanghai.

Norman Alley’s newsreel footage was rushed first to Manila, and then on to Hawaii and California, with a $350,000 insurance policy. The footage added to the growing, albeit muted, outrage in the United States at the incident – some of the large pacifist lobby believed that the US Navy was partly to blame for putting their warships in harm’s way in the first place. The Japanese quickly apologised, although their explanations as to why the attacks continued even after the identity of the Panay was obvious continued to rankle. Still, an indemnity of over $2.2 million was paid and that seemed to quell any feelings about the sinking. The US never came close to intervening in the war. Col Hashimoto, who is perhaps to blame for starting the incident, escaped justice in the immediate aftermath, but in 1947 he was convicted by the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal for unrelated crimes, and sentenced to life in prison. He was paroled in 1954 and died in 1957.

Sources

|

Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945 – Rana Mitter |

|

The Rape Of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust Of World War II – Iris Chang |

|

Yangtze Patrol: The U.S. Navy in China – Kemp Tolley |

Leave a Reply