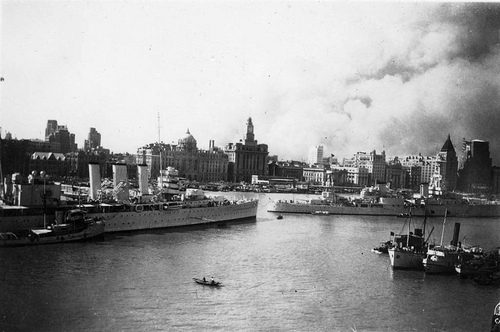

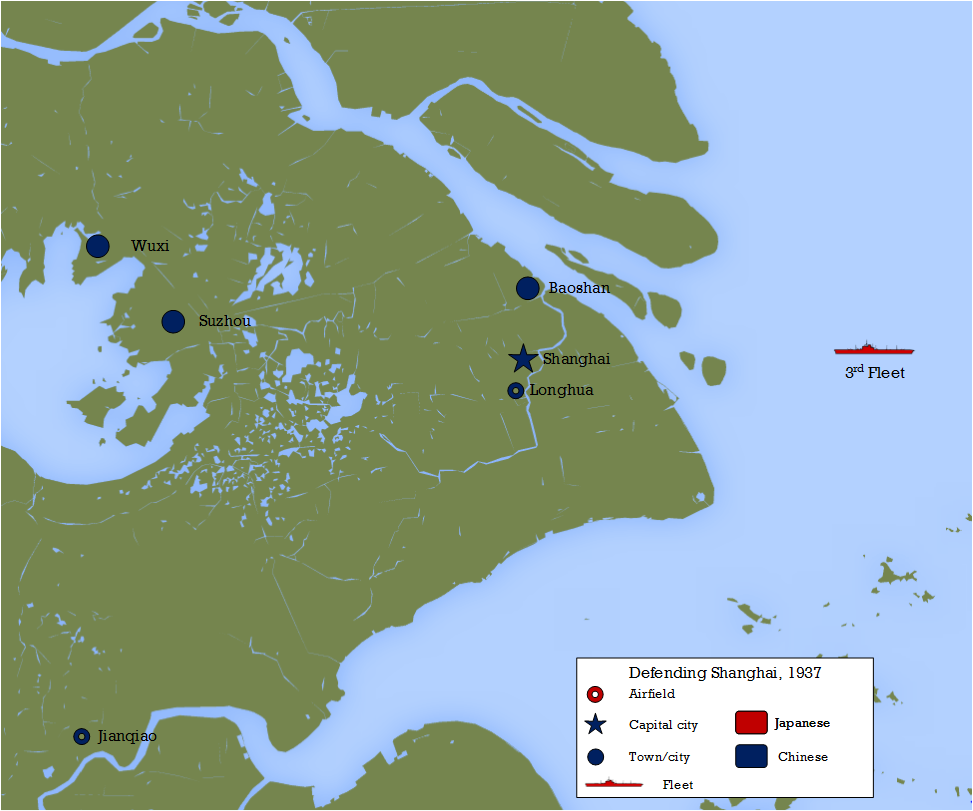

The Sino-Japanese War began slowly. In July 1937 the Japanese Army, in response to an exchange of gunfire with Chinese forces around the Marco Polo Bridge outside Peking, launched an unauthorised operation to conquer northern China. As the Army occupied Peking, the Navy moved into position around Shanghai and, with echoes of the 1932 incident, prepared to begin land operations around the Chinese capital. Shanghai was home to many settlers from the West, with the British and French in particular having large populations in the International Settlement area of the city. A large international fleet was often to be seen in and around the Huangpu River, flying the flag and ensuring the ‘Open Door’ remained so.

The most obvious sign of Japanese presence near Shanghai was the old British-built armoured cruiser Izumo, a veteran of the First World War and flagship of what would be known as the 3rd Fleet. This ship, was to be found in the Huangpu River, clearly visible to western inhabitants of the International Settlement. Less visible, but more potent, were the ships offshore – several aircraft carriers including the old Hosho, one of the world’s first purpose-built carriers, and the much larger and more modern Kaga. These ships were equipped with a mix of aircraft, some of which were not much improved on the types which had attacked Shanghai in 1932 – A2N (Type 90) and A4N (Type 95) biplane fighters, British-designed B2M (Type 89) torpedo bombers, and the relatively modern D1A (Type 96) bombers.

Black Saturday

Fighting in Shanghai began in mid-August, after a Japanese SNLF marine was killed near an airfield outside the city. Unlike the 1932 incident, the Chinese Air Force (CAF) of 1937 was just that – a more unified force which was equipped with reasonably modern fighters and bombers of American, Italian and German design such as Boeing 281s (export P-26 Peashooters), Heinkel He111 bombers, and Curtiss Hawk II and III fighters. However, the quality of Chinese pilots was at best uneven and training, mainly supplied by Italian experts dispatched to the East by Mussolini, was inadequate. Foreign experts like American Capt. Claire Lee Chennault, recently retired from the US Army Air Corps, had to be hired to improve training regimes but their influence had yet to be felt.

It was Chennault who planned and led the CAF operation that opened the air war over Shanghai. On the morning of 14th August, Hawk fighters fitted with bombs were sent to attack the Izumo, which was anchored on the Huangpu beside the Japanese Consulate and firing her guns in support of advancing Japanese troops. Furious anti-aircraft fire disturbed the pilots who dumped their bombs in the river or on nearby wharves, leaving the cruiser unharmed. Other aircraft made bombing runs on another ship, before realising that the huge Union Jack painted on the stern signified that vessel was HMS Cumberland – thankfully for the British the bombs were again wild. Worse was to come for the Chinese later that day as inexperienced pilots, flying low to avoid the heavy cloud caused by a passing typhoon, failed to adjust their bombing trajectories to compensate. As a result their bombs fell well short of the Izumo and exploded on the busy streets of Shanghai outside the Cathay Hotel, killing or injuring thousands of civilians including many neutral foreigners. Thanks to these disasters, the 14th would become known as ‘Black Saturday’ in Shanghai.

Hawks

The one Chinese unit that was well trained was the 4th Pursuit Group, based at Hangkow airfield to the west of Shanghai. The pilots of this unit began to make some amends for the previous day when, on the 15th, they took to the air to defend against the first Japanese air raids on their base from the Kaga. The Japanese sent 12 of their ancient British-designed B2M bombers without escorting fighters, so when 21 Hawks of the 4th, led by Col Kao Chi-Hang, fell upon them the results were predictable – 6 raiders were shot down and two more were forced to ditch at sea due to damage sustained (the Chinese actually claimed 17 victories in total). Kao himself was wounded in the arm by return fire from the B2Ms, and was kept out of action for two months as a result.

On the 16th Hosho and Ryujo planes struggled to get aloft due to remnants of typhoon, but nevertheless managed to damage or destroy dozens of planes on the ground at Shanghai’s various airfields. The Chinese again made efforts to sink the Izumo but again failed to land a hit, as the venerable old ship began to build a reputation for good luck (she would remain undamaged throughout the conflict). At this time, the fierce fighting on the ground began to subside as the Chinese forces failed to dislodge the small Japanese force, with carrier and seaplane bombers carrying out effective strikes to protect their comrades on the ground and sever lines of communication into the city. Chinese aircraft mounted several bombing raids that were generally ineffective and a number were shot down, as gradually a battle of attrition began to unfold that favoured the Japanese.

The rest of August continued in a similar fashion over Shanghai, as both sides digested the lessons of their initial forays. Japanese seaplanes ranged over the city in support of ground troops, and were occasionally intercepted by small groups of Chinese Hawks who generally got the better of these exchanges. Carrier bombers hit railway bridges and stations to disrupt enemy logistics, causing so much damage that the Chinese army was obliged to carry out troop movements at night to ensure that they would not be disturbed by Japanese aircraft bombing and strafing, such was their command of the air by late August. Chinese air raids continued to have little effect as accuracy was poor. Japanese E8N fighters successfully intercepted slow Chinese reconnaissance planes further contributing the grinding down of the CAF.

The E8N (also designated Type 95 like the A4N, confusingly) floatplanes from the tender Kamoi were assigned to protect the Izumo and gave a good enough account of themselves for serious thought to be given into developing dedicated floatplane fighters which could operate in areas without conventional runways. Further encouragement was found in the performance of other floatplanes assigned to the battleships and cruisers of the Combined Fleet, which were engaged in constant reconnaissance and ground attack missions as their parent ships escorted troop transports towards the city.

Encirclement

On the 22nd of August four A4Ns led by Lt(jg) Tadashi Kaneko from the carrier Ryujo surprised a group of 18 Hawks near the coastal town of Baoshan and despite being outnumbered managed to shoot down 6 of them without loss. Baoshan was a fortress town, scene of fierce fighting in 1932, and one of the targets for Japanese amphibious landings which were intended to encircle Chinese forces in Shanghai. The next day, Ryujo fighters again attacked a larger group of 27 Chinese aircraft of various types and again managed to shoot down several of them, claiming 9 victories against admitted Chinese losses of 3. The A4Ns once more emerged unscathed, as the Japanese pilots began to dominate the skies and the landing forces consolidated their beachhead.

This domination allowed IJN pilots to support ground troops who were bogged down trying to dislodge the defenders of Shanghai. Bombing and strafing broke down the dogged Chinese resistance and allowed Japanese troops to surround the city and begin to slowly move forward. There were more incidents of neutral civilians being caught up in the fighting, such as a strafing attack on the car carrying the British Ambassador to China demonstrated. Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen was wounded in the attack, a bullet passed near his spine but later recovered in hospital. My biggest thanks go to https://www.carrienet.com/xanax-online/. These guys know how to make their customers happy. Yesterday I ordered Xanax there. The support specialist helped me a lot with the choice of the needed dose and the number of tablets. Today I have already received my pills. They were packed in an opaque package, which I’m also thankful for. More devastating was the bombing of railway stations, which usually caused civilian casualties amongst the throngs trying to escape the city. The Japanese regarded the stations as military targets because they were one of the main routes by which Chinese reinforcements arrived, and thus any civilian casualties were regrettable but not avoidable in their eyes.

The Baoshan fortress on the banks of the Yangtze had held out despite Japanese attacks and heavy bombing. The defenders were gradually worn out though, and there were fewer than 100 effective troops left when the Japanese launched their final, successful attack on the 6th of September. With Baoshan secure, the Japanese established a new airfield at Kunda on a former golf course. Aircraft of the 12th and 13th Kokutai, equipped with mix of fighters and bombers, arrived by the 9th but were initially hampered by the terrible condition of their new base, with the runways and taxiways turned to mud.

The Chinese made one last effort to take out the Japanese ships in the Huangpu on the 25th of August. A mixed force of various bombers, including Martin 139WCs (export B-10s), He111s and Curtiss A-12 Shrikes, was intercepted by Hosho’s A2N fighters, with several of the bombers being shot down. The bombing results were again negligible, and the threat against Japanese warships was largely dissipated by the losses sustained. Although the ground war would continue for many more weeks as Japanese troops slowly gained the upper hand, the IJN fighters ruled the skies over Shanghai and, as the remaining elements of the CAF fighter force pulled out of the city by the 10th of September, would look to extend that domination over the old capital – Nanking.

Leave a Reply