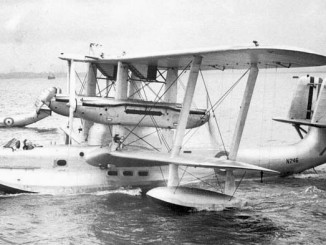

With the Japanese having established a firm foothold on the northern part of the Malayan Peninsula, their troops moved rapidly to capture key British facilities. More army sentai began to fly into the airfields close to the landing grounds, supported by longer range bombers that remained at their bases in Indochina. The Navy bombers of the 22nd Air Flotilla, basking in the glow of their victory over Force Z in the South China Sea, continued to scour the seas whilst also contributing by bombing positions in Malaya and in Brunei and Sarawak, the British colonies on the island of Borneo.

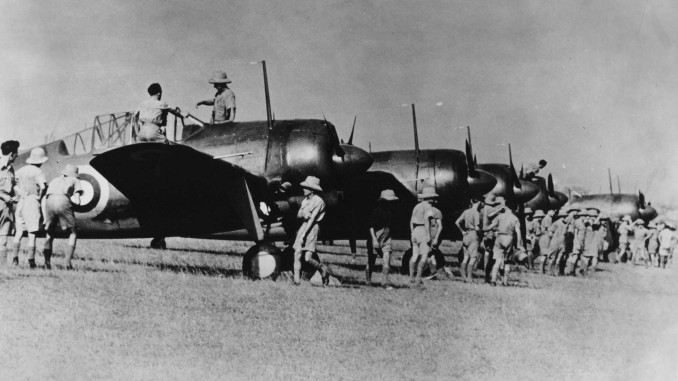

The British were in the difficult position of having to defend northern Malaya with the handful of aircraft that had survived the initial Japanese attacks. Reinforcements were parcelled out from the units based on Singapore island, but the Far East Command was determined to retain considerable air strength to fight off the expected attacks on the fortress city. Most of the bombers had been withdrawn, so all that remained were a few Buffalos of 21 and 453 Squadrons which were scattered among the RAF fields on the west coast of the peninsula.

The Fall of Penang and Kuala Lumpur

Turning their attention south, the Imperial Japanese Army bomber units initially concentrated on the island of Penang, off the west coast of the Malayan Peninsula. For three days beginning on the 11th of December, the Japanese launched repeated attacks. On the first of these days two sentai of Ki-21 heavy bombers, the 12th and 60th, attacked Georgetown and the shipping in the strait between Penang and the mainland. Many bombs fell in civilian areas where casualties were heavy and the fire station was destroyed, hampering firefighting efforts. The following day light Ki-51 and Ki-48 bombers from the 27th, 75th and 90th Sentai arrived to dive bomb merchant ships and Royal Navy auxiliary patrol vessels offshore. The attacks were inaccurate, so although there were casualties amongst the ship’s crews only the gunboat HMS Kampar was badly damaged – she was beached to prevent her sinking.

Responding to these attacks, the commander of the RAF in Malaya Air Chief Marshal Robert Brooke-Popham ordered Buffalos of 243 Squadron to join the handful of remaining 21 Squadron RAAF fighters at Ipoh, giving the British a force of 16 aircraft with which to defend Penang. These were out of position and unable to prevent the Japanese attacking the island again on the 13th, with more light bombers going after the harbour traffic. The patrol ship Tung Wo was damaged and had to be abandoned, and the docks at Georgetown sustained further damage. Diverting from a reconnaissance mission, the 16 Buffalos fell upon the Japanese bombers as they were departing, with Flight Lieutenant Vanderfield shooting down a pair of Ki-48s and his wingmen probably downing a pair of Ki-51s. Japanese Ki-43 fighters were themselves late to join the attack and had to content themselves with strafing Ipoh, but disaster struck when the commanding officer of the 59th Sentai, Major Reinosuke Tanimura, collided with his wingman and was killed in the resulting crash.

The heavy attacks combined with the approach of the Japanese 5th Division convinced the commander of Penang to order its abandonment late on the 13th. However, this order applied only to British troops and European civilians, with the native Malaysians being left to their fate, much to their disgust. In addition to providing air cover for Penang, the Australian Buffalos of 21 and 453 Squadrons (243 having returned to Singapore) launched several strafing attacks on the approaching Japanese columns, on one of these encountering a trio of Ki-51s. One of these was destroyed but Flt Lt White was shot down and killed by return fire from the bombers. The Japanese compounded the situation on the following days by attacking airfields around Penang, claiming several aircraft destroyed on the ground. On the 16th, Penang itself fell without a fight.

With all RAF aircraft now pulling south, the Japanese began to attack the British airfields with vigour. Ipoh was strafed by Ki-43s of the 59th Sentai, who claimed several Buffalos shot down, and this was followed by a bombing attack which destroyed more British fighters on the ground. Attacks continued in this vein on Ipoh for the next few days, which destroyed more Buffalos and force the British to withdraw damaged fighters to Singapore for repairs, leaving just a handful of machines to face ongoing Japanese attacks – these were soon withdrawn to Kuala Lumpur. The Japanese quickly moved forward to captured British airfields around Penang which extended their reach south, and they also captured quantities of fuel and other supplies which were immediately put to use. Kuala Lumpur was immediately the target of Japanese attacks, with raids commencing on the 21st of December during which little damage was done but a Royal Navy vessel offshore, HMS Banka, was sunk. The 59th Sentai claimed four Buffalos shot down, but in actual fact only a single fighter was lost by 453 Squadron.

A large air battle over Kuala Lumpur on the 22nd of December. The newly arrived 64th Sentai under the famous Major Tateo Kato, combined with 59th to launch a vicious strafing attack on the British airfield. They met a dozen patrolling Buffalos over the airfield, and fierce combat ensued. Three Buffalos were claimed shot down by Lt Takayama of the 64th, who then died when his Ki-43 apparently suffered a structural failure and crashed – although he may also have been shot down. Eight further victories claimed, with the actual cost to 453 Squadron amounting to four aircraft and pilots missing and two more badly damaged during crash landings with one of those pilots being fatally injured. A second attack by strafing Ki-43s later the same day resulted in the destruction of a further Buffalo with its pilot, leaving the threadbare 453 Squadron unable to defend its own airfield, let alone any other facility in Northern Malaya. The decision was taken to pull the squadron, the last still stationed in Malaya, back to Singapore, leaving the area to the Japanese.

As had occurred in the Philippines, sustained Japanese attacks had almost completely wiped out an Allied air force less than two weeks after the opening of hostilities. Now Malaya itself was bereft of air cover, with the British holding back the vast majority of their strength to defend Singapore itself, which would soon come under heavy attack.

Leave a Reply