Japan’s war in China brought her into direct conflict with the United States. As Japanese forces moved south into Indochina, the threat to American interests in the Philippines, as well as the British and Dutch colonies in the south seas, grew throughout 1941. When southern Indochina was occupied by the Japanese matters came to a head, with US President Roosevelt implementing an embargo on sales of American oil to Japan – this on top of previous embargoes of iron and other strategic materials. Although talks to end the crisis diplomatically continued right up to the outbreak of war, the Japanese nevertheless began to make preparations for the start of hostilities, whereby they could seize the resources needed to keep the Japanese economy growing.

To neutralise the threat of the Pacific Fleet interfering with operations in the southern area, the commander of the Combined Fleet, Isoruko Yamamoto, produced a plan to attack the main American naval base in the Pacific – Pearl Harbor, on the island of Oahu. The Pacific Fleet had moved its main strength to the Hawaiian Islands in 1940 in response to continued Japanese aggression. A massive first strike on this base would remove the threat of the US Fleet sailing across the Pacific to relieve Allied garrisons under attack by the Japanese, allowing the conquest to proceed unmolested. The implementation of such a plan was Yamamoto’s price for agreeing to support the Army’s Southern Operation, but the technical challenges were formidable.

Kido Butai

The main strength of the Combined Fleet, its 6 modern aircraft carriers, would spearhead the attack. The Japanese battleship fleet would play no part in the operation due to their lack of fuel economy – even the relatively economical carriers and their destroyer escorts would need to be filled to the brim with additional fuel despite the assignment of 7 fleet oilers to the attack force. Four of the carriers – Kaga, Akagi, Soryu and Hiryu – had seen some action during the China war, but the Shokaku and Zuikaku were brand new and untested. The striking force as a whole was known as Kido Butai or “Mobile Force”, The Navy’s most experienced carrier pilots were assigned to the carrier air groups, most having had some involvement in the combat over China – the average pilot had over 800 hours of flying time, very high for a military flyer of the time. They would need every ounce of the skill to carry out what would be an extremely difficult operation.

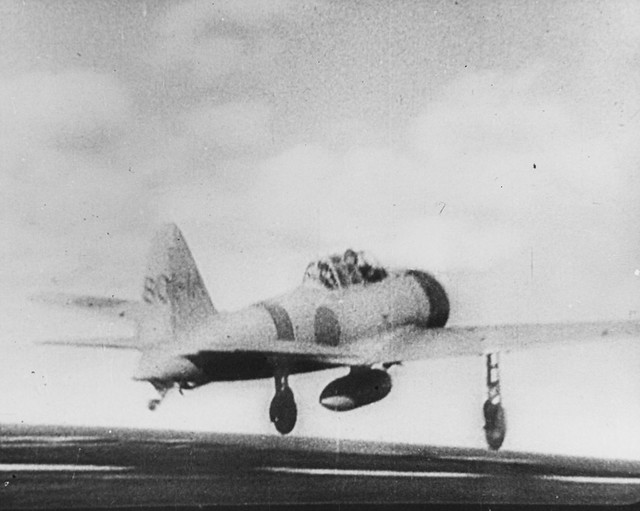

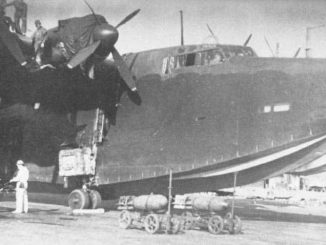

Principle among these difficulties was the depth of Pearl Harbor. Most aerial torpedoes could not be dropped in water less than 75 feet deep, so the Type 91 aerial torpedo carried by the Nakajima B5N was modified by the addition of wooden fins which reduced the depth to which the projectile would plunge after release. This, combined with relentless experimentation and training in the best drop techniques, gave the Japanese the ability to hit some of the American battleships at anchor in the harbour. The practice of mooring these warships in pairs along ‘battleship row’ meant that another weapon would be required to hit those of the inboard line, and so a number of 16-inch battleship shells were modified into 800kg bombs, that could be dropped by further B5Ns operating in the level-bomber role. Aichi D3A dive bombers would use their smaller weapons to attack Oahu’s numerous airfields as well as attacking any warships that the special torpedoes and bombs failed to sink. To round out the attack force Mitsubishi A6M fighters, the infamous “Zero”, would provide escort and ground-strafing support to destroy any American aircraft that might be found.

As the diplomatic situation became untenable, Kido Butai departed Japan on the 26th of November, 1941, and plunged through the North Pacific. A route was chosen which was highly unlikely to encounter any shipping, which allowed the force to approach Pearl undetected. On the 2nd of December the message “Climb Mount Niitaka” was received, which signified that diplomatic efforts had failed and that the attack was definitely scheduled for the 8th of December Tokyo Time – or the 7th of December, Oahu time. Arriving 250 miles north of the island on that fateful day, the carriers launched their attack whilst the Americans slept on, oblivious.250 miles north of the island on that fateful day, the carriers launched their attack whilst the Americans slept on, oblivious.

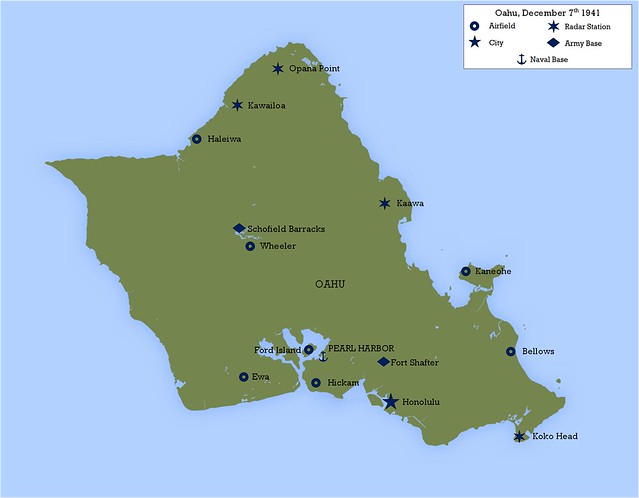

Although both the Army and Navy in Hawaii had been warned about the possibility of war commencing imminently, there was no specific intelligence that Pearl Harbor itself would be attacked. It was thought that the principal threat to American forces was sabotage perpetrated by the island’s large ethnic Japanese population. With this in mind, aircraft parked on Oahu’s six airfields were bunched together so that they could be protected against this more easily. This would prove to be a serious miscalculation that would lead to the virtual destruction of the Hawaiian Air Force during the attack. The Navy judged that submarines lurking off the entrance to the harbour were the biggest threat, and so instituted destroyer patrols offshore. It was one of these, conducted by the destroyer Ward, which found and sank the first of several midget submarines that were launched from motherships just before the air assault began.

The first Japanese aircraft into the air were a pair of E13A floatplanes from the cruisers Chikuma and Tone. These aircraft were to reconnoitre the fleet anchorage at Lahaina Roads as well as Pearl Harbor itself to verify the location of the American battle fleet. The E13As were launched at 0530 and headed south. The Chikuma’s plane was spotted by the Opana Point radar station (which did not recognise the contact as hostile) at 0645 before it reported the presence of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl at 0735 – 9 battleships, a heavy cruiser, and 6 light cruisers. Crucially though the E13A confirmed intelligence reports that none of the Fleet’s 3 carriers was in port. It then headed south to try and find these missing ships. Tone’s plane arrived at Lahaina Roads at 0735 and reported the absence of any American ships there, confirming Pearl Harbor as the primary target.

At 0550 the first wave of the attack force was launched. It consisted of 183 aircraft, although 6 were forced to abort during the launch. This left 48 B5N level bombers with 800kg ‘special’ bombs, 40 more B5Ns with torpedoes, 48 D3As and 41 escorting A6Ms to continue on to Pearl. This force was led by Cdr Mitsuo Fuchida, a veteran of the fighting in China and a leader of great experience and skill. He was riding in the observer position of one of the B5N bombers and would direct the attack, remaining over the target throughout the operation. The incoming raid was detected by the Opana Point radar station at 0702, but the contact was dismissed – it was believed to be an incoming flight of B-17s so no alert was issued – in fact the radar operators were told ‘don’t worry about it’.

Tora! Tora! Tora!

The attackers flew down the west coast of Oahu due to cloud cover over the preferred central route. Several civilian aircraft were encountered, with some being shot down by the escorting Zeroes. Arriving within sight of Pearl Harbor itself, Fuchida realised that complete surprise had been achieved – there were no American fighters airborne, nor was there any challenge from the base’s numerous anti-aircraft batteries. Fuchida fired one flare to signify that surprise had been achieved, but when a nearby group of fighters failed to respond he fired another. A double flare launch signified that surprise was not achieved, which meant that D3As would make the first attack to supress enemy defences, rather than the torpedo bombers. Fuchida also made his famous ‘Tora Tora Tora!’ radio message, announcing to Kido Butai that surprise had been achieved.

First to be attacked was Kaneohe, the naval air station on the east coast of Oahu. It was home to Fleet Air Wing 2’s PBY Catalina flying boats, several of which were moored offshore. Starting at 0748, strafing Zeros and bombing D3As quickly destroyed many of the helpless PBYs, by the end of the raid just a handful remaining airworthy. Other D3As hit Wheeler Field, in central Oahu, at 0751. These landed amongst the densely packed P-36 and P-40 fighters, gathered together in the centre of the airfield to guard against sabotage. Further bombs destroyed the base’s hangars and other facilities. 9 Zeros then came in to strafe any undamaged aircraft, as did some D3As now shorn of their bomb loads. Further attacks were made on Ford Island, the naval air station in the centre of the harbour, Hickam Field, and Ewa Field with much the same result. The seaplane base at the southern end of Ford Island began to burn furiously, with smoke billowing over the harbour.

Death of the Battleships

Meanwhile the 40 torpedo bombers under Akagi’s LtCdr Shigehura Murata had descended to low altitude in preparation for their attacks. Aircraft from the Hiryu and Soryu commenced a run on a battleship moored on the west side of Ford Island, but on this occasion Japanese recognition was faulty – the ‘battleship’ was actually the Utah, now stripped of armament and used as a target vessel. A pair of torpedoes ploughed into her, and she immediately started to take on water and capsize. A further torpedo missed the Utah but hit and damaged the light cruiser Raleigh, moored just ahead. More B5Ns crossed Ford Island and fixated on another ‘battleship’ at the 1010 dock. In fact, this target was a pair of ships, the minelayer Oglala and the cruiser Helena, whose combined silhouette mimicked a more profitable target. A single torpedo hit and damaged the Helena, with four more missing completely.

The remainder of the torpedo bombers, from the Kaga and Akagi, veered south of Pearl Harbor before turned to cross over Hickam Field and commence their runs on Battleship Row. This roundabout route caused the formation to become very strung-out, not ideal now that American anti-aircraft gunners were beginning to reach their stations. In the teeth of furious machine gun fire from the destroyer Bagley, B5Ns dropped their ‘fish’ over a 15-minute period. The first torpedo streaked towards the Oklahoma, with four more subsequent hits following, causing the venerable old ship to turn over. West Virginia was struck by no less than seven torpedoes but sank in an upright position; she would be salvaged. Two more torpedoes hit the California, sinking her, and another hit the Nevada in the bow area. Five of the B5Ns were shot down during their attacks, all from the carrier Kaga, as the Americans began to recover from the shock and man their guns.

The high-level B5Ns with their bombs lined up in ten V formations, each heading for Battleship Row. These were led by Fuchida himself. The plan was for these formations to attack the inboard row of battleships, which could not be reached by the torpedo bombers. One of these formations scored the most damaging hit of the attack, as a pair of 800kg bombs smashed into the Arizona – one of these penetrated her forward magazine and caused a catastrophic explosion, which destroyed the ship and killed over a thousand of her crew. Other bombs hit the California, Tennessee, Maryland, and West Virginia. The repair ship Vestal, moored next to the Arizona, was also badly damaged by a pair of bomb hits.

Into the Maelstrom

Into the midst of the attack arrived a formation of B-17 bombers – the ones that had caused the dismissal of Opana Point’s radar contact. These were from the 7th Bomb Group, en-route to the Philippines to join the Far East Air Force. None of the aircraft were armed, as their defensive guns had been removed for the flight to Hawaii. Zero fighters fell upon the B-17s, causing them to scatter and head for any available landing ground. Two managed to land on the tiny Haleiwa Field, a short fighter strip, with others successfully landing at Hickam. The ruggedness of the B-17s design was apparent as only one of the 12 bombers to make it to Hawaii was destroyed during the attack, despite the best efforts of the Zeros. Several SBD Dauntless aircraft from the carrier Enterprise were less fortunate, arriving in the middle of the attack and suffering 3 shot down and 3 more missing.

The first American fighters to get into position to interfere with the attacks arrived just as the first wave was completing its attacks. A pair of P-40s from the 15th Pursuit Group, piloted by 2nd Lieutenants George Welch and Kenneth Taylor, took off from Haleiwa Field at 0830 and arrived over the Marine Corps base at Ewa Field whilst D3As were engaged in strafing attacks. Each claimed two of the dive bombers shot down, although in actual fact only one was lost. Short on ammunition the two fighters returned to Haleiwa to refuel and rearm.

By 0845 the first wave had largely completed their attack and was beginning to exit the area, whilst the second wave continued to bore in. Most of the damage to the Pacific Fleet was done by the first wave, with four battleships – Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia and California – sunk or sinking and more damaged. The Nevada had been damaged but was getting steam up in preparation for making an escape out to sea. Several other ships had been sunk, representing something of a waste of torpedoes – the Japanese pilots had been instructed not to attack the worthless Utah, for example. Also, the Americans were now fully alerted and had manned as many anti-aircraft batteries as possible. The Japanese had lost just 9 aircraft, but the second wave would not have such an easy time of it.

Leave a Reply