The relatively easy capture of Rabaul in 1942 gave the Japanese a useful base of operations to support offensive moves in the South Pacific. Plans were prepared for landings on the northern coast of New Guinea at Lae and Salamaua, and on the southern coast at the capital, Port Moresby. More distant plans called for the occupation of parts of the Solomon Islands in preparation for attacks on Fiji and New Caledonia, in order to encircle Australia.

Rear Admiral Eiji Goto commanded the 24th Air Flotilla, which was fresh from supporting the occupation of Wake Island and Rabaul itself and had begun to concentrate at airfields around the town to support the New Guinea operations. A detachment of H6K flying boats from the Yokohama Kokutai moved to the seaplane base in Simpson Harbour, and at Vunakanau airfield the newly formed 4th Kokutai arrived with 18 G4M bombers and 27 A5M fighters. The 4th had been commissioned on the 10th of February with Capt Moritama Kahiro commanding, and LtCdr Takuzo Ito in charge of the air echelon. The aircrews had been transferred from the Takao Kokutai and all were veterans of the Philippines and Netherlands East Indies campaigns. The Chitose Kokutai was based nearby at Truk with G3Ms.

The Americans meanwhile had detected the concentration of forces in the south and were preparing moves to blunt the Japanese offensive. Encouraged by the successful Marshalls-Gilberts raid on the 1st of February, the US Navy planned another attack by its aircraft carriers. The Lexington had returned to Pearl Harbor following the failed Wake Island relief expedition, and put her fighter squadron, VF-2, ashore so that it could convert from F2A Buffalos to F4F Wildcats. In the meantime, with the Saratoga under repair after being torpedoed in January, her fighter squadron VF-3 went aboard the Lexington.

Lexington to the Fore

Task Force 11, consisting of the Lexington, three cruisers and six destroyers, was ordered to head south with the oiler Neosho to meet Task Force 8 as it returned from the Marshalls raid, and then escort a convoy to Canton island. Whilst at sea, Rear Admiral Wilson Brown received new orders to take TF11 south to support the landing of American troops on New Caledonia, and he decided that the best approach would be to attack Rabaul to prevent air and naval forces based their interfering with the landings. Brown sent an SBD to Suva, Fiji, to transmit his intentions to Admiral Nimitz in Hawaii and got the necessary approval. He was also informed the intelligence placed the Japanese carrier force in the Netherlands East Indies, where they in fact raided Darwin on the 19th of February. Brown planned to reach launch position within 200 miles of Rabaul on the 21st Feb, and send in cruiser Pensacola and two destroyers to bombard the town after the completion of the initial air strike.

These plans were scuppered on the 20th when, at 1015, Lexington’s CXAM-1 radar detected a contact 35 miles from the carrier. Six F4Fs under VF-3 commanding officer Lt John S. Thach were launched to intercept. The contact was a Yokohama H6K, one of three sent from Rabaul to search the north-eastern sector. At 1030, this plane reported sighting the Lexington and began to trail the task force. Half an hour later, the F4Fs were directed into a rain squall where the H6K was hiding – Thach and his wingman Ens Sellstrom followed as it dived for the deck, and shot it down within sight of the carrier. Shortly afterwards a second H6K, having been ordered to amplify the original sighting, was detected and VF-3 was ordered after it. They quickly shot it down before it could report back to Rabaul.

Admiral Brown decided that, having been forewarned, the Japanese would clear Rabaul harbour and fly in air reinforcements from Truk. He therefore decided to abandon the planned attack, but would feint towards Rabaul before withdrawing at night. He expected an attack by Japanese bombers and was prepared to meet it, with VF-3 maintaining a combat air patrol throughout the day.

The Hard Luck 4th Kokutai

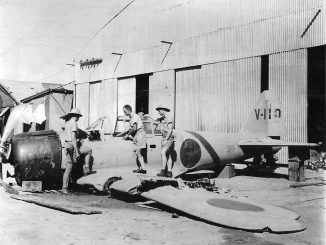

Having received the report of the Lexington’s position, Admiral Goto ordered the 4th Kokutai to launch an attack. The unit roared off from Vunakanau at 1420 with LtCdr Ito in command, with orders to bomb the Lexington – no Type 91 aerial torpedoes were available at Rabaul. One plane was a mechanical dud, leaving 17 to carry out the attack. Two separate chutai set out on the 400 mile flight to the American’s last reported position, one of 8 G4Ms under LtCdr Ito and a second of 9 under Lt Masayoshi Nakagawa. It was Nakagawa’s group that would find the Lexington first.

Shortly after 4pm, Lexington’s radar again registered contacts that rapidly approached the carrier. A fresh division of F4Fs under Lt Noel Gayler had just been launched to relieve six that had been airborne for almost three hours, but landings were then suspended in order to clear Lexington’s deck of fuelled aircraft. Gayler’s fighters just reached the altitude of the intruders in time to intercept them before they made their attacks, spotting the nine G4Ms of Nakagawa’s chutai. Attacking in pairs, the Americans quickly set one bomber aflame, and then two more. Nakagawa set up for a bombing run before his own aircraft was attacked and fell out of formation, shortly followed by a fifth G4M that fell towards the water. Due to the loss of their leader and the radical manoeuvring of the Lexington, the Japanese bomb run was wild, with the nearest bombs landing 3,000 yards from the carrier.

As the surviving bombers turned to run for home, the F4Fs kept up their attacks. One fighter suffered hits in the engine and the pilot, Lt(jg) Howard Johnson, was forced to bail out with wounds to his legs. Landing safely in the water he was soon picked up by a destroyer. A second VF-3 pilot, Ens Jack Wilson, made a poorly-judged stern run on a G4M only to run afoul of the bomber’s 20mm tail cannon. Hits to the F4F’s cockpit area killed the pilot and sent the fighter spinning into the sea. Lt Thach and his wingman shot down two of the remaining bombers, whilst SBDs from VS-2 finished off two other stragglers. None of the G4Ms from Nakagawa’s chutai would return to Rabaul.

Meanwhile, a lone G4M, clearly heavily damaged, approached the Lexington at low level. The pilot clearly intended to execute a ‘body crashing’ suicide attack on the carrier, but he was thwarted by heavy anti-aircraft fire which finally brought the bomber down just astern of the Lexington.

The attack had caused great difficulties for the Lexington’s fighter direction office. The rapidly unfolding situation, with many contacts that had to be managed, had overwhelmed the small staff responsible for air defense. The CXAM radar set did not give a visual indication of the location of targets as did later version, instead requiring air defence staff to manually plot each contact on a chart. As a result, Ito’s chutai had managed to approach within 30 miles of the carrier before it was noticed, and soon after confirmed by visual sighting.

O’Hare to the Rescue

With most of VF-3’s fighters having chased after the Nakagawa chutai, only two F4Fs were available to oppose Ito. This was Lt Edward “Butch” O’Hare and his wingman Lt(jg) Marion Dufilho. The pair quickly moved in to attack, and in his first firing run O’Hare badly damaged two G4Ms, both of which dropped out of formation. Dufilho was forced to peel off with jammed guns, leaving O’Hare to claim two more bombers on his next pass.

By now the G4Ms, surrounded by burst of anti-aircraft fire from the ships below, were approaching the release point for their bombs. O’Hare therefore concentrated on the lead aircraft of LtCdr Ito to disrupt the bomb release. Pouring fire into the G4M’s port engine, O’Hare caused the motor to explode. The engine itself came away from Ito’s aircraft, which itself plunged downward, severely damaged. The remaining four G4Ms released their bombs, the closest of which exploded just 100ft astern of the Lexington. O’Hare was concentrating on his sixth target when his guns stopped firing, his ammunition exhausted.

Ito’s aircraft, piloted by Warrant Officer Watanabe, recovered from its dive in time to make an attempt to ‘body crash’ on the Lexington. Losing speed due to its missing engine, the lead G4M faced withering fire from the carrier and her escorts and dumped its bombs to reduce weight. Lexington made a radical turn to avoid the bomber, which failed to follow this manoeuvre and instead passed near the ship, possibly with the flight crew dead at the controls. Slowly the G4M lost height, and crashed in a fireball that the Lexington was forced to avoid sailing through. The surviving bomber crews of the 4th Kokutai, watching this scene from 10,000ft, reported that Ito and his crew had successfully crash-dived the carrier.

As the five surviving G4Ms withdrew, they faced opposition from VF-3 fighters that were looking for stragglers. Ens Sellstrom came across the remaining formation of four bombers led by Lt(jg) Mitani and shot the leader down – Mitani was the last surviving officer of the 4th Kokutai. Other G4Ms faced further harassing attacks from F4Fs before VF-3 was forced to break of, low on fuel and ammunition. The four remaining G4Ms, all severely damaged, then faced the long flight back to Rabaul. Two would not make it the full distance – one was forced to ditch near New Ireland, and the other ditched in Rabaul’s Simpson Harbour. The two that did make it back to Vunakanau required extensive repairs before they could fly again. In total 15 G4M bombers were lost, 13 with their entire crews. To add to the woes of the Japanese, a H6K flying boat and an E13A reconnaissance seaplane, both sent out to trail the American task force, failed to return. Thus the 24th Air Flotilla lost a total of 19 aircraft in the attempt to sink the Lexington. A night sortie by six torpedo-armed flying boats failed to find the carrier, which had by this point set course for home and was rapidly departing the area.

The star of the aerial battle was undoubtedly Lt O’Hare. He was officially credited with five Japanese bombers destroyed, to become the US Navy’s first fighter ace of the war. VF-3’s commander, John Thach, recommended that he be awarded the Medal of Honor. Despite O’Hare’s protestations that the award was unnecessary, the recommendation was approved by Admiral Nimitz and in April O’Hare travelled to the White House to receive the award from President Roosevelt himself.

The air battle had showed the value of the US Navy’s deflection gunnery techniques, which gave the F4F fighter the best chance of dispatching enemy bombers whilst reducing the effectiveness of defensive fire from their turrets. The vulnerability of Japanese aircraft design was also evident, with the 4th Kokutai’s G4Ms proving unable to resist the F4F’s firepower. However, gaps in the air defence capabilities of the carrier fleet were evident – radar interpretation and fighter direction techniques were still in their infancy, and but for O’Hare’s excellent shooting may have spelled disaster for the Lexington. The sheer number of contacts threatened to overwhelm the small staff aboard the carrier, and only the prudent decision to keep O’Hare’s section in reserve to await developments led to Ito’s chutai being opposed in its attack. VF-3 had a standard complement of 18 F4F fighters, and as with the Marshalls-Gilberts raid earlier in February it was clear that this was simply too few to adequately meet the demand for fighters to provide escort and fleet defence services.

Leave a Reply