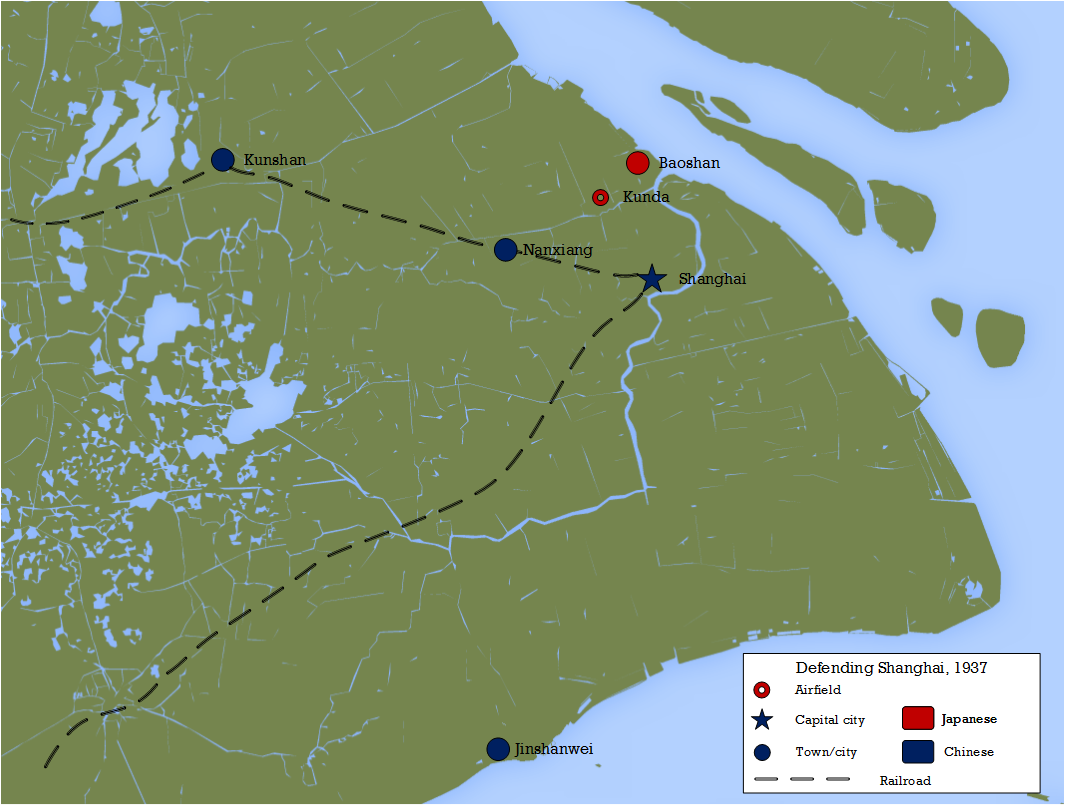

The Battle of Shanghai continued into October 1937. After the Japanese had successfully landed at Baoshan, on the southern bank of the Yangtze, they failed to follow up this success with further gains. Pushing south from Baoshan, to the west of Shanghai itself, the Japanese Army ran into strong resistance along the Suzhou Creek. For much of October, the struggle to break this line of resistance would require the full attention of the 2nd Rengo Kokutai as it sought to assist the forces attempting to complete the encirclement of Shanghai. Here they would prove the effectiveness of naval air power in the support of troops involved in a land operation.

Support for the Army

After largely destroying the Chinese air forces over Nanking and disposing of the Chinese Navy in the Yangtze, the 12th and 13th Kokutai could turn their attention to giving close support for the army. On the 29th of September 1937, agreement was reached between the commander of the 2nd Rengo Ku and the Shanghai Expeditionary Force on a policy for co-operation, with the details worked out the following day. The focus of the support would be on villages in front of the Japanese 3rd and 9th Divisions, where Chinese troops were suspected to be based, as well as Chinese rear positions and lines of communications. Of particular importance was the Chinese artillery corps, which was still within range of important Japanese bases, including Kunda airfield.

In addition to the 2nd Rengo Ku, the Japanese would also commit a special unit of the Kisarazu Kokutai. Like the Kanoya, the Kisarazu had suffered heavy losses of its G3M Type 96 bombers over China, and so it had deployed to Cheju-Do the only existing G2H Type 95 bombers. The G2H was the Naval Air Force’s first attempt at a large, long range bomber aircraft. It had such obsolete features as fixed landing gear, fixed-pitch wooden propellers, and open cockpits. A total of 8 of these had been manufactured by the Hiroshi Naval Arsenal. One of these had crashed during testing, and another was lost to unknown causes on the journey to Cheju-Do, leaving just 6 of the big aircraft available. Slower than the G3M but capable of carrying much heavier bomb loads, the G2Hs would be used to smash towns and villages where the Chinese army was suspected to be based.

The 2nd Rengo Kokutai began its attacks on the 1st of October. The air offensive opened with massive raids by D1As and B3Ys on positions all along the front lines. Particular attention was paid to the villages of Waikangchen and Chiating, both of which were believed to be the location of Chinese army headquarters positions. Villages in front of the 9th Division were heavily bombed in order to pave the way for an advance of those ground troops. The heavy assault continued the next day – in total over 150 sorties were launched by the 12th and 13th Ku over the first two days of attacks. In response, Chinese artillery shelled Kunda airfield, destroying or damaging several aircraft on the ground, forcing the Japanese to seek out the artillery positions the following day.

By the 5th of October, thanks in part to the support of the IJNAF, a number of small bridgeheads across the Suzhou Creek had been made. The Chinese launched fierce counterattacks to try to contain these, in the knowledge that no further natural obstacles stood between the Japanese and the complete encirclement of Shanghai. Of particular importance was the main Chinese artillery force, which was based at Nanxiang and protected by heavy antiaircraft defences which largely kept Japanese bombers away. Efforts by the 2nd Rengo Ku were further hampered by foul weather, which kept all planes on the ground for three days from the 9th of October.

The Japanese brought additional reinforcements into the Shanghai area in the middle of October, as the Imperial Japanese Army began to transfer its Sentai (air groups) and Chutai (squadrons). First to arrive was the 10th Independent Chutai with its Ki-10 fighters. Whilst the 2nd Rengo Ku carried out the duel tasks of supporting the army and supressing enemy air strength around Nanking, the 10th Chutai was largely used as a protective force over Shanghai, in concert with the 12th Ku’s A4N fighters. The Chinese were using their remaining bombers to carry out attacks by night over the city; on the 14th of October a total of 18 were sent to bomb airfields and warehouses, with largely indifferent results. The following day, two Martin 139WC bombers were involved in separate crashes. The 10th Chutai added to the Chinese bomber force’s woes when SgtMaj Kiyonori Sano, flying his Ki-10 in the night skies, shot down a bomber – the first Japanese victory claimed by night.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Rengo Ku was continuing its effective work in supporting the ground offensive. On the 11th, a special attack was launched in the Shanghai Electric Power Company headquarters, where ‘special intelligence’ indicated that a meeting between top officers was being held. More than 50 were believed to have been killed in the attack. Less effective, and more shocking, was a strike that destroyed a tram in the International Settlement, killing several of the occupants including an 18-month old child. Still, the weight of the attacks began to break the stalemate as the Chinese line began to crumble – an attack on the village of Yangchiaochiao was estimated to have killed 2,000 Chinese troops. To further press home the attacks, the 12th and 13th Ku were each given individual tasks. The 12th was ordered to seek out the previously difficult to hit artillery positions of the Chinese, whilst the 13th was tasked with seeking out and destroying lines of communication to the front – particularly trains, road vehicles, and canal junks. By this time the Japanese pilots had become extremely adept at bombing, sometimes within very close proximity to friendly lines.

The Hiro G2H

The G2Hs of the Kisarazu Ku were also kept busy, disgorging their huge bomb loads over key positions. The big Type 95s were mainly used to reduce key towns and villages along the front, paying particular attention to the town of Nanxiang. Carrying four times the payload of the G3M, they were able to carry out effective strikes, including one on the 21st at Kunshan which destroyed an enemy headquarters. Mainly though the G2Hs were employed in the destruction of houses and other buildings in front of Japanese troops, not purely military targets. Doubtless the civilian casualties caused by this were extremely high, contributing to the heavy death-toll of the Battle of Shanghai – the Chinese suffered an estimated 300,000 killed, wounded and missing in just 3 months of fighting.

The bomber force was to suffer a huge setback on the 24th of October. The G2H was notorious for problems with its Hiro W-18 engines, which delivered enough power to get the big plane airborne but suffered from chronic reliability problems. As engines were started for another raid on the Shanghai area, one of the bombers suffered a fuel leak on its engine which quickly caught fire. It wasn’t long before the fire was out of control, causing the aircraft’s bomb load to detonate. In the ensuing explosion four G2Hs were completely destroyed, and a fifth was damaged beyond repair. That left just a single remaining airworthy bomber. This final G2H was pressed back into service on the 29th, flying a solo raid on Chingpuchen. On the way to the target this plane was badly hit by Chinese anti-aircraft guns and fire quickly took hold. The last G2H was able to make an undignified emergency landing at Wangpin airfield, but did not fly in combat again.

Retreat

Despite the loss of the G2H force, the 2nd Rengo Ku was able to make its attacks tell. A Chinese counter attack, launched on the 23rd, was quickly broken up as D1As and B3Ys carried out a series of withering attacks on villages along the front. The Chinese 174th Division, only recently arrived in the area, was almost completely destroyed by bombing and began to withdraw. This was the beginning of a collapse across the entire front, with retreating Chinese troops harried by further bombing and strafing attacks at every town and village behind the front line. By the 27th, the Japanese army was advancing so rapidly that it was not possible to effectively co-ordinate bombing raids, so the 2nd Rengo Ku was largely confined to carrying out harassing raids on the retreating Chinese forces.

To further complicate matters for the Chinese, the Japanese army landed thousands of troops near the fortress of Jinshanwei on the coast of Hangzhou Bay, to the south of Shanghai. Bad weather kept IJNAF aircraft grounded as the troops waded ashore on the 5th, but thereafter the 2nd Rengo Ku was able to provide effective support as this new force pushed north to complete the encirclement of the city.

The Chinese army, meanwhile, was in in full retreat. The remaining troops were falling back pell-mell on Nanking, occasionally putting up limited resistance at the main railway towns on route – at Wuxi, a Chinese stand was routed in just two days. Before long, the Japanese were at the gates of the old capital. The final Chinese troops holding out in Shanghai itself were gradually rooted out and destroyed, with the battle itself finally ending on the 26th of November. The city was now securely in the hands of the Japanese, who decided to expand the scope of their operations and take Nanking, which was by now largely indefensible.

The Battle of Shanghai was the first time that Japanese air forces had operated in support of a major land campaign. The Japanese Naval Air Force in particular had proved itself capable of delivering effective air support to help destroy a powerful and tenacious enemy army, whilst simultaneously eliminating an enemy air force, albeit one equipped with mostly obsolete aircraft. Most of all, the success of Japanese-designed aircraft proved that the indigenous aeronautical industry was able to produce high quality aircraft. No longer was Japan required to import designers and engineers from Europe in order to produce decent aircraft – something that the watching Western nations failed to take note of.

Leave a Reply