After two months of fighting, neither side had made a decisive breakthrough in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol. Although the Japanese had failed in their first attempt to claim the disputed area, they were determined to make a fresh assault and were building up their strength accordingly. The Soviets, meanwhile, were shuttling in fresh reinforcements from European Russia in order to blunt the Japanese attack and lay the groundwork for their own counter-offensive.

The Soviets reviewed the performance of their aircraft during the initial stages of the Battle of Khalkhin Gol and noted the poor performance of some of their fighter pilots. They were unable to give adequate escort protection to SB-2 bombers, which were forced to increase their bombing altitude as a result. Better oxygen equipment went some way to solving this problem. A number of veterans of the Spanish Civil War also pioneered strafing attacks on enemy airfields, based on their previous successful experience with this tactic.

Bomber commanders themselves noted the poor results that they were achieving, and so a number of changes to their doctrine were instituted. Several bombing raids during were launched during July where gradual improvement in accuracy was observed, and Japanese fighters proved less able to effectively intercept due to the higher altitudes employed. On the 22nd of July, the Japanese proved unable to intercept a raid by 15 SB-2s, which provided encouragement although bombing results remained poor. Formations were therefore closed up to try and decrease the size of the ‘pattern’ of bomb impacts, and the number of aircraft in each formation was increase to add further weight of bombs to each attack.

The Japanese, meanwhile, were finding that their fighter crews were increasingly fatigued after 3 months of combat. The new Soviet tactics proved difficult for the Ki-27 units to counter, as the Nakajimas proved unable to climb to meet the SB-2 raids – their only option being to maintain constant high altitude patrols which were extremely hard on both men and machines. Additional Sentai were being brought forward to alleviate the strain, but in the meantime the burden would remain on the shoulders of the 1st, 11th and 24th Sentai with their Ki-27s.

The Skies of Nomonhan

The 23rd of July saw heavy air combat, as both sides launched massive bombing raids along the front, sparked by a new Japanese ground offensive. The Soviets launched 8 different attacks, totalling 140 SB-2 sorties, covered by heavy fighter escorts flying a total of 150 sorties. The Japanese launched over 120 sorties of their Ki-21 and Ki-30 bombers, paying particular attention to Soviet command posts and airfields in the rear which were welcoming fresh air reinforcements into the theatre. There was constant fighter combat over Lake Buir-Nur as both sides attempted to intercept the other’s bombers. Japanese claims were again highly exaggerated, with 48 victories recorded against confirmed Soviet losses of just 4. Further bombing was conducted on the 24th, although Soviet losses were heavier as several SB-2 were lost to Japanese flak and fighters.

A Soviet mission to destroy Japanese observation balloons sparked a huge fighter furball on the 25th, as over 200 aircraft clashed in the skies over Mount Hamar-Daba. All of the Japanese Ki-27 units were involved, whilst the Soviet 22nd and 56th IAP provided the bulk of the VVS contingent. The Japanese claimed 59 for just 2 losses, with MSgt Tomio Hanada accounting for 5 enemy fighters. Several downed Japanese fighters were bravely rescued by comrades setting their aircraft down on the steppe, sometimes within yards of onrushing Soviet tanks.

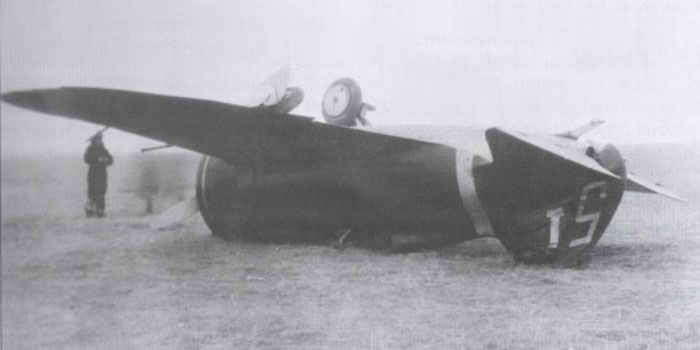

On the 29th the 22nd IAP opened the day by launching massed strafing attacks on Japanese airfields with follow up SB-2 raids contributing to the destruction. Many of the 24th Sentai’s Ki-27s were rendered unserviceable, with 12 destroyed during the attack. Senior pilots Capt Sanji Kani and 2Lt Syoichi Suzuki (with 17 claims to his name) were killed as they attempted to get their fighters airborne in the midst of the attack. The 1st and 11th Sentai attempted a revenge attack but Soviet pilots met the Japanese with overwhelming numerical advantage, with the result that more Ki-27s met the fate of their brethren. Among the pilots lost was Major Fumio Harada, who was captured – he eventually died in captivity in 1940, allegedly killed attempting to lead an escape attempt by PoWs.

July had proved to be a tough month for Japanese, one where they lost 40 aircraft – treble the losses of the previous month. The VVS had lost 79 aircraft (against over 380 claimed destroyed by the Japanese). The Soviets had largely abandoned the use of their old R-5s for reconnaissance due to the losses sustained by this type, and were experimenting with using I-16s and SB-2s for scouting and photo reconnaissance. The Japanese had likewise discovered the extreme vulnerability of their Ki-36 light bomber when it was not covered by fighters. By the end of July it was clear that the Japanese were definitely losing control of the air – many Sentai and Chutai leaders had been killed or wounded and the shortage of experienced senior pilots was becoming apparent. The Japanese Army Air Force did not have a policy of rotating pilots to rear areas for rest and recuperation, partly due to combined needs of the simultaneous wars in both Nomonhan and China. This foreshadowed the Japanese experience of the Pacific War, where veteran pilots were kept at the front until they were killed or invalided home.

On the 2nd of August the base of the 15th Sentai, a recon unit equipped with Ki-15 and Ki-36s, was attacked by the 70th IAP – 23 I-16 strafers covered by 19 more I-16s as escort. The Japanese were completely unprepared and their aircraft were not dispersed, and as a result 12 of their machines were destroyed on the ground. Colonel Katsumi Abe, commanding officer of the 15th was killed during the attack. Thereafter the Japanese avoided Soviet bombing raids by having their aircraft in the air whenever one was detected. This policy led to more major battles like the one the followed on the 5th, with the Japanese claiming 27 Soviet fighters destroyed during the interception of another strafing attack – the Soviets admitting just 2 actual losses. Poor weather descended on the fighting front on the 6th, limiting the air action to a few raids by Ki-30s. The 61st Sentai with their Ki-21s were sent away from the combat zone for rest and reorganisation.

During an attempted strafing attack by I-16s was thwarted by the appearance of 11th Sentai Ki-27s on the 7th. During the ensuing fighter combat MSgt Daisuke Kanbara shot down an I-16, and then landed to kill the pilot with his samurai sword – evidence that the war was becoming much less civilised.

The Japanese planned a third major assault for 24th August. Air power was massed on key airfields, with plans laid for a massive strike in support of an advance by 75,000 troops supported by hundreds of artillery pieces. However, the Soviets had been busy bringing in air reinforcements, which meant that by mid-August they had three times the number of aircraft that the Japanese had available.

Zhukov’s Whirlwind

Zhukov launched his long-awaited counter-offensive at dawn on August 20th. The day opened with Soviet bombers making attacks on Japanese anti-aircraft positions, which were followed by more I-16 strafing attacks against the same targets. Once these attackers had departed a massive Soviet artillery barrage opened up, as almost 150 fighters patrolled over the front to prevent Japanese aircraft interfering with the assault. Later in the morning a massive strike by fifty SB-2s, escorted by three regiments of fighters, plastered Japanese positions. The few Ki-27s that were able to get into position were caught by the I-153s and I-16s, some of which were armed with new RS-82 rockets – an air-to-ground weapon which was nevertheless used against enemy fighters effectively. Fighters on ground were not safe either, as the Soviet I-16 strafers became ever more effective. The 64th Sentai lost half a dozen Ki-27s to a strafing attack on Djindjin-Sume, plus 2 more shot down trying to scramble.

In all the Soviets launched over 1000 sorties on the day of the attack. Japanese forces, massing for their own scheduled attack a few days hence, took a fearsome pounding from the Soviet artillery barrage and immediately began to give under the pressure of Zhukov’s tank assault. On the 21st, the second day of the offensive, the Japanese launched a few raids on Soviet airfields which had only limited success, destroying a few SB-2s on the ground. Thereafter the VVS fighters made their numbers tell as they fell upon the Ki-27s and Ki-30s. During the day VVs claimed 27 fighters and 7 bombers destroyed, whilst the IJAAF claimed 45 in return. This would prove to be the heaviest day of combat of the entire ‘incident’.

The 22nd was much quieter. The Japanese attempted raids on Soviet armour as it advanced, but these failed completely as Soviet fighters intercepted raids by Ki-30s and Ki-21s. The pattern was repeated over the next few days as the Japanese 23rd Division was surrounded by advancing Soviet forces, despite the efforts of the Japanese air support units. Massive Soviet fighter formations were constantly airborne over the front, intercepting the Japanese whenever they appeared. The Ki-27 escorts were incredibly hard pressed to protect their charges due to a desperate shortage of fighters. The 33rd Sentai, equipped with the now obsolete Kawasaki Ki-10 was pressed into action. Worse was the continued loss of experienced pilots, including the 58-victory ace WO Shinohara who was killed in air combat on the 27th.

The 31st of August was the last day of land combat. With the 23rd Division surrounded and destroyed, and all other Japanese units cleared from Mongolian soil, the end of the conflict was clearly near. Soviet aircraft were prohibited from crossing the border. On the 1st of September Germany invaded Poland, and Stalin was anxious to conclude the Nomonhan Incident so that he could concentrate on claiming his share of the spoils in Europe. The Japanese launched a number of late air raids whilst ceasefire talks were ongoing, but the massed power of the Soviet fighter regiments, who concentrated on protecting the now entrenched ground troops by destroying the attacking Ki-30 bombers in the air.

Wintery weather descended on the area on the 6th of September, becoming gradually worse. The Japanese attempted a final series of raids on the 14th and 15th of September, hoping to strengthen their negotiating position, but despite managing to destroy several fighters on the ground the Soviets beat off the worst of the attack. The cease-fire agreement signed on the 15th of September, to take affect at 1pm on the following day.

The conflict showed some of the flaws inherent in Japanese aircraft designs – light and nimble machines with limited firepower were no match in a prolonged conflict for the heavier, faster, better protected Soviet types, especially the I-16. The Japanese practice of not rotating combat units or even individual pilots out of the action periodically meant that many senior pilots stayed in action until they were killed or wounded, a practice that would be maintained by both the Army and Navy air wings throughout the Pacific War. The Battle of Khalkhin Gol also influenced western opinions on the fighting qualities of the Japanese. Having failed to complete the conquest of China, the Japanese Army had now crumbled when faced with a European adversary. Did the US or Britain have anything to fear?

Leave a Reply