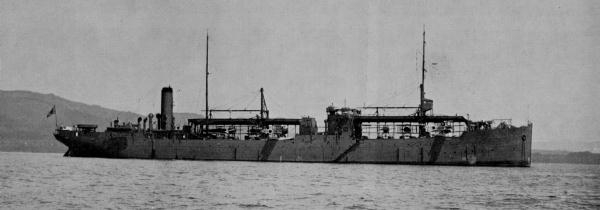

In September 1931, the Japanese staged the ‘Mukden Incident’ and eventually invaded and occupied Mukden, Manchuria, ejecting the ruling Chinese in the process. After Chinese boycotts of Japanese goods in response to this incursion, Japanese naval forces were despatched to Shanghai to ostensibly protect Japanese possessions in the area. This sparked a short but violent conflict in the city. The Shanghai Incident, as the Japanese would name the upcoming battle, began at dawn on the 28th January 1932. The seaplane tender Notoro launched several of her seaplanes to drop flares in order to frighten Chinese civilians and troops during the advance of the Japanese Navy’s Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF). The SNLF then advanced towards the Chinese 19th Route Army, which was in position around Shanghai.

The next day, the Notoro launched more of her E1Y floatplanes to bomb and strafe Chinese possessions in the Chapei sector, including artillery positions and the North Railway Station. Weather conditions were extremely poor and it is doubtful that the pilots had a clear view of their targets.Civilian loss of life was reported as heavy, some sources claiming ‘thousands’ of casualties, and some writers, such as the eminent historian Barbara Tuchmann, have described this attack as history’s first ‘terror bombing’ of non-combatants. However, official figures for the death toll are impossible to find, and given the lack of capability of the E1Y3 floatplane (already ancient in 1932 and capable of carrying just 200kg of bombs and a single 7.7mm machine gun) it is hard to believe that Notoro’s flyers could have inflicted such a large amount of punishment. Moreover most sources describe the targets as military in nature, and although civilians were undoubtedly victims of the attack it seems unlikely that they were the primary target.

Despite the attention of the Notoro’s seaplanes, the SNLF advance had bogged down in the face of opposition from the 19th Route Army and support had to be requested from the Japanese Army. Meanwhile the carrier Kaga with 24 A1Ns and 36 B1Ms, and Japan’s first aircraft carrier, the Hosho, had arrived with her 22 aircraft – 10 A1N fighters, 9 B2M bombers and 3 C1M reconnaissance planes. These began launching attacks on Chinese positions and on the 5th of February, three A1N fighters accompanying two bombers encountered the first aerial opposition from the Chinese. After a brief combat with 9 Chinese fighters, both sides withdrew without losses. Indecisive air combat again occurred on the 19th of February, this time with a Boeing 218 fighter piloted by Robert M. Short providing opposition to the Japanese.

Short was assigned by his American employers to deliver fighter aircraft to the Chinese, but decided to intervene in a more direct way when he saw Japanese planes airborne during a ferry flight. In this first combat he was credited with shooting down Lt Kidokoro Mohachiro’s A1N, but Mohachiro managed to limp back to base (he was later killed during the American invasion of Kwajelein in 1944). 3 days later Short was again airborne in a 218 fighter when he encountered three B1Ms escorted by three more A1Ns. During a 10 minute battle, Short made numerous attacks on the bombers, shooting down a B1M before he was himself shot down and killed by fighter pilot Lt. Ikuta Nogiji – the first aerial victory by the Japanese Naval Air Service. Short was lionized in the Chinese press and his funeral included a reported 500,000 mourners lining the streets of Shanghai.

The involvement of Robert Short highlights the weakness of the Chinese Air Force. In fact, there was no official ‘Chinese Air Force’, as the defence of China was in the hands of local warlords – the Chinese fighters in the skies over Shanghai were bought and purchased privately by those warlords. Training was patchy and the available aircraft were a strange mix of different models and manufacturers. In later years the Chinese would seek to import more and better aircraft, as well as a training specialists and, eventually, foreign mercenary pilots.

On the 26th of February one of the largest Japanese raids so far, of 9 B1Ms and 6 A1Ns, was intercepted by five Chinese fighters. The defenders got the worst of the fight, with three fighters being shot down. All the Japanese planes returned to base safely. On the 1st of March the 19th Route Army was surrounded by Japanese troops and forced to capitulate, leaving Shanghai undefended. The Shanghai Incident was brought to a close by a cease-fire agreement shortly afterwards. At the same time Japan proclaimed the existence of Manchukuo, the puppet state carved out of the former Manchuria.

Of particular concern to the Japanese during the conflict was the poor performance of her fighter aircraft. Robert Short had managed to set upon half a dozen B1M bombers and deal them heavy punishment, including shooting one down, before the inferior A1Ns had finally managed to dispatch the plucky American. This was all the more concerning because the Chinese Air Force was so weak – a more capable foe with modern aircraft in higher quantities may have inflicted more grievous losses. Consequently, programs were put into motion to replace the largely foreign-designed types in service with more capable, indigenous designs. A replacement for the A1N was already being designed even as the cease-fire was agreed.

The Shanghai Incident set the stage for the Second Sino-Japanese which was to break out 5 years later. It involved the first prolonged use of aircraft carriers during a continental conflict, and demonstrated their usefulness in supporting expeditionary forces ashore – which would prove key during the wider Pacific War a decade later. It also featured one of the largest air conflicts since the Great War, highlighting how little aircraft technology had advanced in the intervening period – the state of the art still featured biplanes with maximum speeds of perhaps 150mph. by the time of the later conflict, however, much would have changed.

Leave a Reply