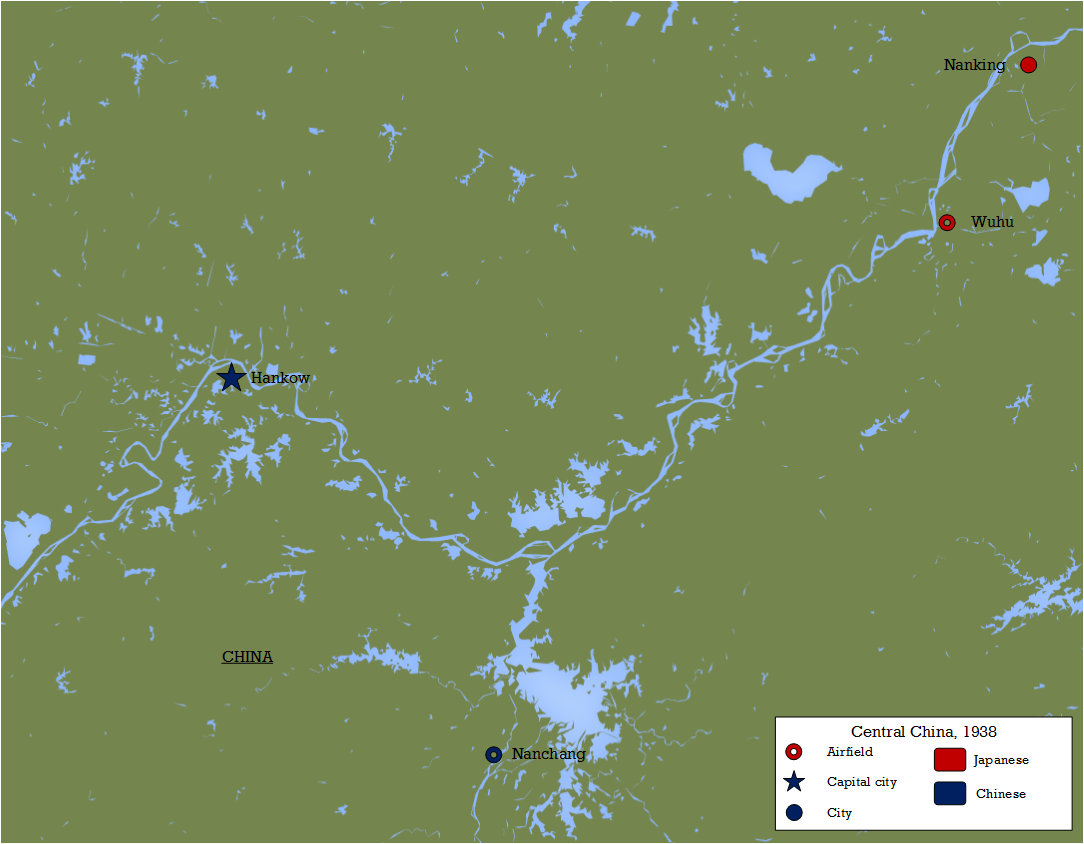

In November 1937, with Shanghai secured, the Japanese turned their attention on Nanking. The old capital was devoid of any worthwhile defences so the Chinese decided not to fight for the city as they had for Shanghai. Accordingly the government made arrangements to withdraw to the tri-city of Wuhan, several hundred miles inland up the Yangtze River. The Soviet Volunteer Group, as well as Chinese pilots flying new Russian fighters supplied via Operation Zet, would have their first taste of combat as the Japanese forces closed in on Nanking. With the pre-war Chinese Air Force down to its last few Hawks, the reinforcements came just in time. In the skies over the capital the new aircraft would be tested to the limit as the Japanese reached a peak in efficiency and skill.

The Soviet Volunteer Group in action

On the 21st of November, 1937, the Soviet pilots had their first encounter with their Japanese counterparts. An attack by the 2nd Rengo Kokutai on Nanking was intercepted by the Kurdyumov fighter group (less their namesake leader, killed during the trip to China). This initial encounter went the way of the Russians, as they claimed a bomber and two “I-96” fighters (as the Soviets called the A5M). The next day, the Prokofyev group had their baptism of fire as they intercepted a 13th Kokutai raid on the city – this time the Japanese got the upper hand as PO3c Kanichi Kashimura claimed two I-16s shot down, with a solitary A5M claimed in return by the Soviets. Lt. N. N. Nezhdanov of the SVG was killed in this attack. A further interception on the 24th resulted in two further Japanese aircraft claimed shot down, as the volunteers began to assert themselves.

The air fighting intensified during December as the Japanese closed in on Nanking. On the first of the month the Soviet pilots were launched on 5 separate interceptions, with a total of 10 bombers and 4 fighters claimed shot down. In return the Japanese shot down two I-16s, but both pilots were able to parachute to safety and fly again. On the 2nd, the first group of Soviet SB-2 bombers, led by M.G. Machin, flew their first mission against the Japanese. Machin led 9 of his bombers on a deceptive course that took them out to sea, before they turned back inland to hit the Japanese airfield at Kunda. The tactic worked, as the defending fighters were not able to intercept the SB-2s until after they had completed their attack. Machin claimed a dozen planes destroyed on the ground and a further two damaged in the air, as well as an auxiliary cruiser sunk in the Yangtze. The same day, however, the Japanese again raided Nanking and claimed 13 Chinese fighters shot down.

The Ki-10s of the 10th Independent Chutai also made an appearance over the city. On the 3rd, a group of the Army fighters escorted a reconnaissance flight to Daijiaochang airfield, where they encountered enemy fighters, claiming 8 shot down in the air and a further 2 burned on the ground. 13th Ku fighters and bombers in a follow up raid were less fortunate, as the Soviet pilots swooped in to claim 3 bombers and an A5M – one bomber being claimed by Leytenant Dimitriy Kudymov. The next day, the 13th Ku returned to Nanking and Sea1c Kaneyoshi Muto claimed the first of his 28 total aerial victories.

With the fall of Nanking imminent, the Japanese switched their attention to Chinese airbases further behind the lines. On the 9th of December a major raid by G3Ms of the 1st Rengo Ku, by now operating from bases around Shanghai, was escorted to Nanchang by 8 A5Ms of the 13th Ku. A group of Hawks intercepted the raid, claiming one of the A5Ms destroyed before the escorts turned the tables and shot down 3 of the Curtiss fighters. As the G3Ms rained their bombs down on the airfield, claiming 20 aircraft burned, the A5Ms claimed a total of 12 Chinese and Soviet fighters destroyed whilst losing a single fighter of their own. One of these was claimed by PO3c Kanichi Kashimura, who also suffered a mid-air collision with a disintegrating Hawk, but he managed to bring his A5M back to base minus a large portion of his port wing. Kashimura’s plane was destroyed in the subsequent crash-landing but the pilot walked away without a scratch.

By now the Japanese controlled the largely controlled the skies over the capital. This allowed them to carry out attacks on Yangtze River traffic almost with impunity, which led directly to the Panay Incident on the 12th of December. The city of Nanking fell the next day, the 13th, but a plan was conceived for the Soviet bomber force to strike back quickly. On the 15th, the Machin group with SB-2s plus 9 more bombers with Chinese crews, mounted a raid on Daijiaochang airfield which was now in Japanese hands. Bombing with a mix of high explosives and incendiaries from medium altitude, the SB-2s turned the target into cauldron of fire, claiming 40 aircraft burned out. In return, one of the Chinese SB-2s was claimed by A5Ms as the bombers made their escape. SVG gunners claimed to have shot down 4 enemy fighters during the withdrawal.

In the weeks after the fall of Nanking, the Chinese and Japanese bomber forces carried out a number of tit-for-tat air raids on each other’s airfields. On the 4th of January, 1938, A5Ms of the 2nd Rengo Ku escorted bombers to Hankow, where they claimed four more Hawks shot down and the bombers destroyed a pair of Gammas and a V-65 Corsair on the ground. The next day, SB-2s attack Wuhu aerodrome, south of Nanking – claiming 5 enemy aircraft burned out on the ground. These attacks continued throughout January, culminating in a large attack on Daijiaochang by SB-2s. The 1st Rengo Ku with their G3Ms had recently shifted to the airfield, after first transferring to airfields around Shanghai. The SB-2s, led by F.P. Polynin, attacked on the 26th of January with 13 bombers. They claimed on extraordinary victory – 40 or 50 aircraft destroyed on the ground, as well as damage to the airfield facilities. The Japanese admitted losing just a handful of G3Ms, but did themselves manage to bring down an SB-2 with anti-aircraft fire. A5Ms attempting to intercept, forced Polynin’s bomber to ditch near the Yangtze. Helpful locals took care of his crew, and loaded his SB-2 onto a barge for transport back to Hankow. A revenge raid the next day on Hankow was thwarted as the Chinese and Soviet pilots, alerted by an early warning observation net put in place by Claire Chennault, flew to safety before the attackers arrived. The Japanese lost a G3M to the Chinese defences and did not cause any appreciable damage.

These battles wore down the remaining Hawk units, with very few of the Curtiss fighters still combat ready. Consequently, squadrons like the 26th Pursuit Squadron were withdrawn from combat and sent to Lanzhou to retrain on Soviet fighters. The Chinese government had already requested an increase in the supply of Russian aircraft as the Japanese proved so successful in downing the motley collection of fighters that had comprised the air force at the start of the war. The 28th and 29th Pursuit Squadrons were re-equipped with British Gloster Gladiator biplanes, 36 of which had been ordered in the autumn of 1937. These aircraft arrived in Hong Kong during October, but the Japanese objected to their being readied for service there so the crated fighters were shipped to Canton. Assembly was completed in January, and the Gladiators were flown to Nanchang.

The new fighters were sorely needed. On the 18th of February, one of the largest air battles of the war in China occurred when the Kanoya Kokutai sent their G3Ms to Hankow, with a heavy escort of 26 A5Ms. A gaggle of Chinese I-15s and I-16s, 29 in all, attempted to intercept. The Chinese were again well served by their network of observers, and were able to take off before the Japanese arrived but were unable to reach fighting altitude before the A5Ms of the 12th Ku fell upon them. Amongst the first to fall was Captain Lee Kuei-Tan, commander of the 4th Pursuit Group. His I-15 caught fire and crashed as he attempted to bring it in for an emergency landing. Another I-15 from Lee’s group was destroyed, whilst a third was able to limp home riddled with bullet holes. I-15s of the 22nd Pursuit Squadron, not far behind, also lost their leader when Captain Liu Chi-Han was forced to bail out of his burning fighter – but not before claiming an A5M that had shot down one of his wingmen. 2 other I-15s, attempting to attack the same A5M, ended up colliding, with only one of the pilots able to escape by parachute. The 23rd PS, arriving from their own base, tore into the Japanese and allowed a number of their 22nd PS comrades to escape. The A5Ms quickly reacted, dispatching two of the newcomers. The Soviet I-16s also piled into the attack, and claimed a total of 12 enemy planes shot down including one by the Spanish Civil War veteran Georgiy Zakharov. The Japanese did not escape unscathed – Lt Takashi Kaneko, commander of the 12th Ku, was shot down and killed during this battle.

The Attack on Formosa

Realising that they had to take the initiative, the Chinese Air Force hatched a plan for the Soviet bomber force to launch a deep strike on the Japanese rear. The airbases of Formosa were selected as the target, in what would be a reverse of the over-water bombing raids carried out by the 1st Rengo Ku from August 1937. 28 Soviet SB-2s, followed by a further 12 with mixed Chinese/Russian crews, would attack Matsuyama airfield. Although the Kanoya Ku had vacated the base, it was now being used as an assembly point for Fiat BR.20 bombers, which the IJAAF had ordered from Italy. The raid would be carried out on the 23rd of February, the 20th anniversary of the founding of the Red Army.

The 12 SBs with mixed crews failed to find the target so it was left to the Soviets, again led by Polynin, to do the damage. Taking a route that initially took the bombers far to the north of Formosa, Polynin was able to approach undetected. The airfield target was obscured by heavy clouds, but these dispersed just in time for the SB-2s to see the uncamouflaged BR.20s in various states of assembly around the field. Surprise was total, anti-aircraft fire was sporadic and Japanese fighters were unable to scramble quickly enough to make an interception attempt. A total of 280 bombs were dropped, with the attackers claiming that 40 aircraft were destroyed on the ground as well as several hangars and a 3 year supply of aviation fuel. None of the attackers suffered any appreciable damage. The attack proved to be a terrible humiliation for the Japanese, and the base commander reportedly committed hari-kari rather than live with the shame of having presided over the disaster.

The Japanese response was predictable. The G3Ms of the 1st Rengo Ku assembled for their biggest raid so far, with 35 of their bombers sent to destroy the Nanchang aerodrome, suspected as the staging point of the Formosa raid. 18 A5Ms provided the escort for the raid on the 25th. Around 50 Chinese and Soviet fighters were in the air and they suffered the worst of the exchange as the A5Ms, as the Japanese claimed an enormous total of 27 victories and 13 probably destroyed. The Chinese admitted losing 6 aircraft in the air and an SB-2 on the ground, claiming 3 A5Ms destroyed, whilst the SVG lost 6 planes and 3 pilots killed. Two Japanese pilots were killed.

The arrival of the Soviet Volunteer Group and the supplies of replacement aircraft provided the Chinese Air Force with a much needed shot in the arm. The air battles over Shanghai and Nanking had been heavy and prolonged, but as the fighting moved west the intensity of the aerial action increased markedly. The Japanese had learned from the heavy losses suffered and provided much heavier escorts for their bombers, which themselves began to operate in much larger numbers in order to provide better mutual protection and a heavier punch when attacking Chinese airfields. As the Japanese closed in on Hankow, the scene was set for some of the fiercest air battles yet.

Bibliography

|

Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945 – Rana Mitter |

|

Polikarpov I-15, I-16 and I-153 Aces (Aircraft of the Aces) – Mikhail Maslov |

Leave a Reply