In December 1941, with the shock of Pearl Harbor still evident, many senior commanders in the United States expressed a desire to hit back directly at Japan. President Roosevelt himself was amongst the first to suggest such a course of action, but head of the Army Air Force Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold and incoming Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Ernest King were both advocates of a bombing raid directly on Tokyo itself. Such a raid would raise morale in the US and dent the aura of invincibility that surrounded Japan, as her forces were winning a string of victories in the south seas. Capt. Francis Low of the US Navy was at the Norfolk naval air station and saw an Army bomber taxiing past a practice ‘carrier deck’ painted on the tarmac, and suggested to King that Army bombers might be able to operate from a Navy carrier and conduct such a strike.

Gen. Arnold enthusiastically embraced the idea, and appointed LtCol James Doolittle to examine the idea in more detail. Doolittle examined the characteristics of the Army bombers then available, to decide which one was best suited for carrier takeoffs. Both the B-18 Bolo and the B-23 Dragon were rejected due to the width of their wingspans. The B-26 Marauder, which Doolittle had spent several weeks evaluating after a series of training accidents in the type, was also rejected due to its difficult low-speed flying characteristics. The B-25 Mitchell was a docile aircraft with short wingspan, and although it lacked the fuel to fly the intended course it appeared the most suited to the role, if enough additional fuel tanks could be carried.

The 17th Bombardment Group (Medium) had the most experience with the new B-25, having flown them for almost a year. Crews were asked to volunteer for an unspecified but dangerous assignment, with each of the group’s four squadrons contributing men until 22 complete crews were available. The plan was to include a total of 15 bombers on the strike, with spare crews available in the event of late illnesses or withdrawals – it was made clear throughout the selection and training process that any man could choose to end his participation at any point with no ill-will, although none ever took advantage of this.

The men of the 17th reported to Eglin Army Air Base for training in Navy-style short take-offs, under the tutelage of naval aviator Lt Henry Miller. Pilots and co-pilots learned the best techniques to take off at low speed with a very short run – throttling up the engines to full power but holding the bomber by its brakes, then releasing the brakes and pulling back on the stick to take to the air at speeds as low as 65mph, and distances of less than 500ft. They also learned to keep their aircraft rolling in a straight line, to avoid the potential of their wing tip striking a carrier’s island structure. The B-25s were also modified, with unnecessary items removed to save weight and additional fuel tanks fitted.

On completion of training, 16 B-25s flew to Alameda Naval Air Station in San Francisco Bay 31st March. They were then loaded on to the new aircraft carrier Hornet, which had just completed her shakedown cruise in the Atlantic and was scheduled to join the Pacific Fleet. The 16th bomber was also loaded, so that Miller could demonstrate the correct takeoff technique after the ship had departed and was underway – however, it was decided to instead take this B-25 all the way to Tokyo. Hornet and her escorts departed from San Francisco Bay on the 2nd of April.

The Hornet joined up with Admiral Halsey’s Task Force 16, with the carrier Enterprise and her escorts, north of Hawaii. The entire force then set out for Japan, operating under radio silence. The B-25 crews and the men of the task force were then informed of the target of the raid – Tokyo, with some of the B-25s also hitting Yokohama and Nagoya. Ordnancemen enthusiastically scrawled messages for Emperor Hirohito and the people of Japan on the bombs as they were loaded into the Mitchells. Japanese medals presented to Americans before the war were attached to some of the bombs, in a ceremony on Hornet’s flight deck.

The original plan was to launch the bombers late on the 18th of April, allowing them to attack Tokyo at night and then fly on to airfields around the city of Chuchow. However, these pans were scuppered when radar detected Japanese surface craft that were being used as advanced pickets. The task force changed course, to avoid these, but a dawn patrol by Enterprise SBDs reported more vessels nearby. The cruiser Nashville was ordered to sink these, as were several more SBDs, but these efforts could not stop warning messages being sent back to Japan. Halsey therefore decided that to keep his valuable carriers safe, he had to launch the raiders immediately despite being several hundred miles from the intended launching point. It was now very doubtful that the B-25s could reach the airfields in China before running out of fuel.

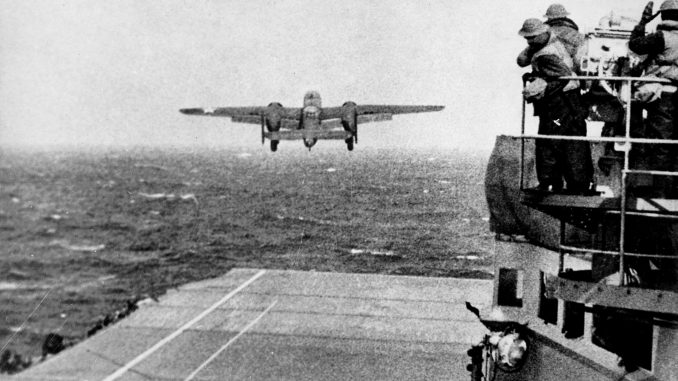

Nevertheless the Army aviators took to their task enthusiastically. The seas were very rough as the B-25s’ engines were started and warmed up. Doolittle was the first to attempt the take off at 0820, with the shortest amount of deck to work with. His Mitchell staggered into the air, nosed down alarmingly, and then gained level flight. He was followed at roughly 4 minute intervals by the other 15 bombers, each of which circled the carrier to check compass bearings before setting out for the target in small groups. Halsey’s carriers, their job done, turned back for Hawaii.

The Japanese were relatively sanguine about the report of carriers. They believed that any attack would be launched the following day, expecting that the Americans would close to within range of their single-engine aircraft (about 200 miles). They did not expect a long range attack from 700 miles out on the same day as the sighting. Therefore, anti-aircraft defences and Army interceptor Sentai were not at full alert when the Mitchells arrived at around 1.30pm.

Target Tokyo

Each raider was assigned a series of targets, with latitude to attack any military or industrial target. Ten bombers headed for Tokyo, whilst the others flew further to Yokosuka, Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe. Doolittle was the first to attack, spotting his target – an army arsenal – in northern Tokyo. His bombs mostly landed on target, although some of his cluster munitions landed on a school, killing a student and a passerby. Other targets hit or near missed by the other bombers over Tokyo included armouries, steel mills, foundries and aircraft factories. Damage in all of these attacks was relatively light, and nearby civilian structures also suffered under the bombs.

The other six bombers spread out to attack lesser cities. A prime target at Yokosuka was the drydocked submarine depot ship Taigei, which was in the process of being converted to the light carrier Ryuho. This ship suffered a direct hit which delayed her re-launch for several months. Other targets included refineries, steel plants and dockyards – again damage was light, but the value of the raid was more in the shock it gave to the Japanese defence establishment than the actual impact on production. One of the B-25s jettisoned its bombs after being damaged by fighter attacks – these were probably conducted probably first pre-production models of the Kawasaki Ki-61. Other fighters attacked B-25s after they had hit their targets, and two were claimed to have been shot down by gunners on the Mitchells. Anti-aircraft fire throughout the raid was light and inaccurate.

A total of 13 targets were hit during the raid, although total damage was very light, especially in comparison to the heavy bombing attacks that would occur in 1945. Damage to each of the facilities was repaired quite quickly. The damage to the Ryuho was the most quantifiable, delaying her completion for several months. Around 50 people, mostly civilians, were killed and around 400 wounded during the Doolittle Raid, which was used as the justification for the ‘prosecution’ of some of the airmen. Perhaps the most damage was done to Japanese pride, as was evidenced in the extreme behaviour displayed during the response to the attack.

Having completed their attacks, the crews contemplated the flight to China and made hurried calculations of how far they could fly with their remaining fuel. Capt Edward York decided to abandon the plan to fly to Chuchow, and instead turned north intending to fly to Vladivostok in the Soviet Union. All of the crews were under strict instructions not to enter Soviet airspace in order to avoid antagonising the Japanese-Soviet relationship, however York elected to ignore this. His B-25 safely made it to an airfield outside Vladivostok.

The other 15 bombers continued on for China, aware that their chances of reaching the intended airfields were low. All managed to reach the Chinese coast, but two were so low on fuel that they had to ditch offshore, with two men drowning as a result. Unable to find a suitable place to land, all of the other bomber crews elected to bail out. One man died having failed in the attempt, his body being found near the wreckage of his bomber. Several other men suffered severe injuries during the ditchings or when they landed in their parachutes.

Aftermath

Assessing the situation, the crews had to find transportation that would allow them to reach Chungking or other cities where they could receive assistance from American forces. Many of the locals did what they could to help the Americans, guiding them towards western missionaries who helped them make their way to safety. Most of the men were able to escape to safe havens, some barely escaping discovery in the attempt. However, eight men were soon captured by Japanese Army patrols. The Japanese responded to the arrival of the raiders in China by launching an offensive to capture Zhejiang province, which had been largely ignored during the Sino-Japanese War. An estimated 250,000 people died during this offensive, many in brutal fashion, as the Japanese Army exacted revenge for the assistance given to the Americans.

The eight captured Americans also suffered terribly. After months in captivity in a prison near Shanghai, the men were abruptly tried for the ‘war crime’ of bombing civilians in Tokyo. They were given no opportunity to defend themselves, and it was little surprise that each was sentenced to death. Five men had their sentences commuted to life in prison, but three – 1Lt Dean Hallmark, 1Lt William Farrow, and Cpl Harold Spatz, were executed by firing squad on 15th October 1942. Another man, 1Lt Robert Meder, died of malnutrition in December 1943, having received starvation rations for the length of his captivity. The four survivors, all badly malnourished and kept in solitary confinement, survived to be released by American forces after the Japanese surrender in August 1945. Capt York’s crew was interned in Russia, before ‘escaping’ across the border to Iran in May 1943 – actually the crossing was staged by the NKVD.

Doolittle was initially despondent at the results of the raid. Little damage had been caused, and every bomber had been lost. Doolittle therefore expected to be court martialled and punished for the failure. However the Joint Chiefs in Washington, in concurrence with President Roosevelt, instead nominated Doolittle for the Medal of Honor and most of the other men received lesser awards. The raid was to have fateful consequences for the Japanese, as the embarrassment helped Admiral Yamamoto gather the support he needed to implement his plan to trap and destroy the American carriers once and for all – a plan which would lead to the cataclysmic meeting of the Combined Fleet and the Pacific Fleet at an island called Midway.

The Royce Special Mission to the Philippines made NYT page 1 headlines for a couple of days before it got knocked off by the Doolittle Raid. The Royce mission proved the range and versatility of the new B-25C, caused some damage to the Japanese in Cebu and Davao, evacuated important civilian and military personnel to Australia, and lost no crew members during the four-day mission. The Doolittle raid dominated because it made a physical attack on the Japanese homeland.