One of the lesser known aspects of the air war in the Pacific is the extent to which the Japanese made use of submarine-launched aircraft. Although several navies had experimented with submarine aircraft carriers between the world wars, only the Imperial Japanese Navy seriously pursued the concept. The French Navy developed the large cruiser submarine Surcouf, whilst the British modified their submarine M2 to carry small seaplanes which could be partially disassembled and stored in waterproof hangars built into the vessel’s hull. Both of these experimental ships were one-offs and neither the French nor the British took the concept further. The German Kriegsmarine and the US Navy both examined the idea but never progressed to the point of deploying prototypes. The Japanese Navy meanwhile developed an extensive fleet of 42 large submarines which were capable of carrying aircraft.

The first of these was a modification of the Junsen Type submarine. The fifth vessel of this class, I-5, was the first Japanese submarine to be completed with storage for a single tiny E6Y floatplane, which could be partially disassembled. To launch, the plane was assembled on deck and floated off, before it took to the air under its own power. However, this method proved inadequate and I-5 was fitted with an air-power catapult. Follow on Junsen Type, Mod II and III submarines included this addition as part of their standard design as completed. This was very useful given the lack of engine power available to the tiny floatplanes carried aboard – the Yokosuka E6Y had just 160hp available at full power. I-5 entered service in 1932 and served as the test-bed for later aircraft-carrying submarines which were commissioned from 1935 onwards. Several of the Junsens supported the Japanese war in China from 1937 onwards, flying reconnaissance sorties in support of the blockade of that country.

The Junsen Types were followed by four Type A submarines, which were slightly larger and had better aircraft carrying capabilities. This allowed the Type As to carry the larger and more powerful Watanabe E9W, which greatly increased the capability of the submarine-aircraft tandem. The Type As were commissioned in the year leading up to the start of the Pacific War. It was immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, on the 16th of December, that the submarine I-7 launched her E9W to reconnoitre the damage done to the Pacific Fleet. The pilot reported seeing several damaged battleships, as well as a carrier, five cruisers and 30 other vessels. Upon return to the mother ship, the E9W was damaged and the crew had to swim to I-7, which then scuttled the plane and soon made good her escape.

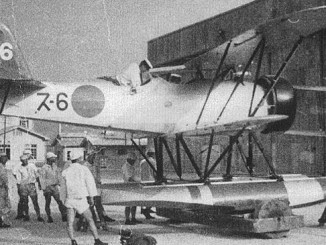

The largest single class of submarine aircraft carriers were the Type Bs, 29 of which were completed with aviation facilities. These saw extensive service across the Pacific and were perhaps the most successful Japanese submarine design of the war. By the time they entered service they could take advantage of the latest model of small reconnaissance seaplane, the Yokosuka E14Y Type 0, which was slightly faster and longer-legged than the E9W whilst also being able to carry a modest bomb load. Many of the Type Bs were converted to act as motherships to midget submarines, in which role they participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. I-19’s E14Y reconnoitred Pearl Harbor on the 4th of January, 1942, and reported on the progress of repairs. I-9’s E9W then made a repeat visit on the 23rd of February.

Perhaps the most famous, and certainly the most experienced, of the submarine aircraft carriers was the Type B I-25. She had been part of the Pearl Harbor attack force, and had been ordered to hunt for the American carriers that escaped destruction. Immediately afterwards she was ordered to the US coast, where she attacked a tanker during an otherwise fruitless patrol, before returning to Kwajalein. Here she replaced her E9W with an E14Y and survived a strafing by American aircraft during the raid of the 1st of February.

On the 8th of February, I-25 departed Kwajalein with orders to patrol and reconnoitre various locations in Australia and New Zealand. She arrived off Sydney on the 15th, but rough weather delayed the launch and it wasn’t until the 17th that pilot CPO Nobuo Fujita and observer PO2c Shoji Okuda could take off in their floatplane. They overflew the capital’s Botany Bay and counted a total of 23 ships in the harbour, before returning safely to the I-25. Nine days later, the same crew flew over Melbourne and attracted the attention of RAAF fighters and anti-aircraft crews, before again returning safely. A flight over Hobart followed on the 1st of March, before I-25 headed for New Zealand. Wellington was scouted on the 8th of March, and Auckland on the 13th, before Fujita and Okuda attempted to find a cruiser and merchant ship that had been briefly spotted by lookouts. Finally, I-25 sailed to Fiji for a final overflight, before ending her patrol at Truk.

Sydney Harbour Midget Sub Attack

I-25’s patrol to Australian waters served as a prelude to an attack planned for late May. With the Japanese in the planning stages for Operation MI, the attack on Midway, two separate attacks by submarines were planned as distractions – one on the recently captured port of Diego Suarez on Madagascar, the other on Sydney Harbour. The 8th Submarine Squadron was tasked with carrying out both of these widely separated locales. The Eastern Attack Unit consisted of I-21 and I-29 carrying E14Ys, and I-22, I-24, I-27 and I-28 with midget subs. I-24 suffered battery explosion and was scrubbed from the mission soon after leaving Kwajalein. First to arrive off Australia was I-29, which launched its E14Y on the 23rd of May. This flight was detected by an RAAF radar unit, but dismissed as a glitch. The day of the raid, on the 29th, I-21 launched her own floatplane for a final reconnaissance which mapped the locations of Allied ships, noting that the battleship Warspite was not present, but that the American cruiser Chicago was. Upon landing the E14Y was damaged and had to be scuttled, but the mission was a success.

The three midget submarines launched on the 31st of May. M-14, launched from I-27, became tangled in the harbour’s anti-submarine nets and was depth charged by one of the patrol craft, before the crew of the sub set off scuttling charges. This destroyed the vessel and killed the two crew. M-24 penetrated the defences and was not spotted until it was close to the Chicago, which spotted the midget and opened fire. Backing off and waiting for the situation to calm down, M-24 later fired both of her torpedoes towards the cruiser. Both missed and instead hit a nearby quay, but the concussion from those impacts sank the stores ship HMAS Kuttabul and damaged the Dutch submarine K-IX. M-24 then escaped from the harbour but never made it back to its mothership – the wreck was discovered in 2006. The final midget submarine, M-21, was depth charged by three Australian patrol boats and sunk. The five large submarines stayed in the area for several days, with I-21 and I-24 shelling positions at Newcastle and Sydney on the 8th of June.

Operation MI and Operation AL

Several other aircraft-carrying submarines were involved in Operation AL, the invasion of the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska timed to coincide with the Midway operation. Amongst these was I-25, which carried out a floatplane overflight of Dutch Harbour on May 27th, and I-9 which performed similar flights over Adak and Kodiak islands. However the most important reconnaissance flight was one to investigate Pearl Harbor itself. In a reprise of Operation K, the bombing of Oahu in March 1942, several submarines arrived near the French Frigate Shoals in anticipation of the arrival of a Kawanishi H8K flying boat. However, American ships were stationed in the area and the mission was cancelled. One wonders if the subs used to attack Sydney and Diego Suarez might have been better utilised in reconnoitring Pearl, given subsequent events.

Flight operations for these reconnaissance missions were often very difficult. Aircraft handling facilities on board the submarines were primitive, and it was only after extensive drilling that crews were able to extract the aircraft parts from their watertight containers and assemble the machine on the exposed deck. Poor weather or a rough sea-state could make aircraft launches difficult or impossible – several missions had to be cancelled or postponed until conditions improved. Finding the mothership at the end of each mission was challenging, with submarines forced to use a system of smoke floats to highlight their position – a risky proposition close to Allied bases. Likewise, landing on the ocean at the end of the flight was also a difficult proposition – several aircraft were damaged on landing, many of them beyond the limited repair facilities aboard such small vessels. Many floatplanes had to be abandoned or scuttled after their missions.

The Solomons Campaign

Submarines saw extensive service during the Guadalcanal campaign, during which they carried out several reconnaissance missions to keep tabs on the Allied bases on New Caledonia and in the New Hebrides islands. The Japanese were initially slow to react to the American invasion of Guadalcanal, and the submarine force was no exception. Submarines played only a limited role during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons in August, but in September the effort improved with several boats being deployed to meet the threat. Submarine reconnaissance played a role in this effort. I-31 bombarded an Allied seaplane base on San Cristobal, before sailing to the New Hebrides. Her E14Y overflew Vanikoro on the 11th and 13th of September, and in early October I-21’s floatplane discovered an Allied airfield under construction on Espiritu Santo.

Other submarines acted as refuelers for seaplanes, as a ‘mini Operation K’ was instituted. Several boats lurked near the Indispensable Reef, south of Rennell Island and Guadalcanal itself. E13A Type 0s from the seaplane carrier Chitose, which was based at Shortland Island, flew to the reef, refuelled from the submarines, then flew further to search the waters southeast of the Solomons hoping to discover Allied movements. The non-seaplane carrying I-122 initiated the service, followed by I-17 and I-26. The duty was hazardous, as I-26 discovered when she was attacked by American B-17s. although the bombs missed, the submarine grounded and damaged her torpedo tubes.

The End of the Reconnaissance Effort

With Allied air power making itself a nuisance to the submarines, further flights by seaplanes became increasingly hazardous. Many of the submarines were converted so that the aircraft compartments could be used to carry cargo, and the I-boats were used to ferry supplies and ammunition to the beleaguered Japanese garrison on Guadalcanal in much the same way that American submarines had attempted to supply bases in the Philippines. Other submarines served in the same capacity in the Aleutians, where the contributed to the successful evacuation of Kiska before the Americans re-occupied the island in 1943.

With the close of the Guadalcanal campaign, the aircraft-carrying submarine fleet greatly reduced its operations. Although overflights of Allied bases in the South Pacific were occasionally conducted during 1943, the effort was not as sustained as it had been during 1943 – a situation not helped by the loss of several of the boats to anti-submarine units. Two further missions to reconnoitre Pearl Harbor were flown in October, by I-36, and November, by I-9, 1943. The E14Y launched by I-36 failed to return from the mission and it may have been shot down by anti-aircraft fire. The last reconnaissance flight appears to have been that flown by an E14Y from I-10 on the 12th of June, 1944. This aircraft flew over the new American base at Majuro, and discovered that the American carrier fleet had departed – it was at that time attacking the Marianas.

Leave a Reply