As the fighting erupted in Shanghai in August 1937, the Chinese authorities began to look to the great powers of the west for assistance. The first to offer meaningful help was the Soviet Union, with which Chiang Kai-shek signed the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact on August 21st. As part of the terms of this treaty, the USSR agreed to provide monetary support in the form of grants. However, the most important agreement was over a secret provision for the USSR to supply China with first-rate aircraft, which would be organised under the code name “Operation Zet”. These aircraft, mainly I-15 and I-16 fighters and SB-2 bombers, were amongst the finest in the world and had already seen extensive combat during the Spanish Civil War, where they had acquitted themselves well.

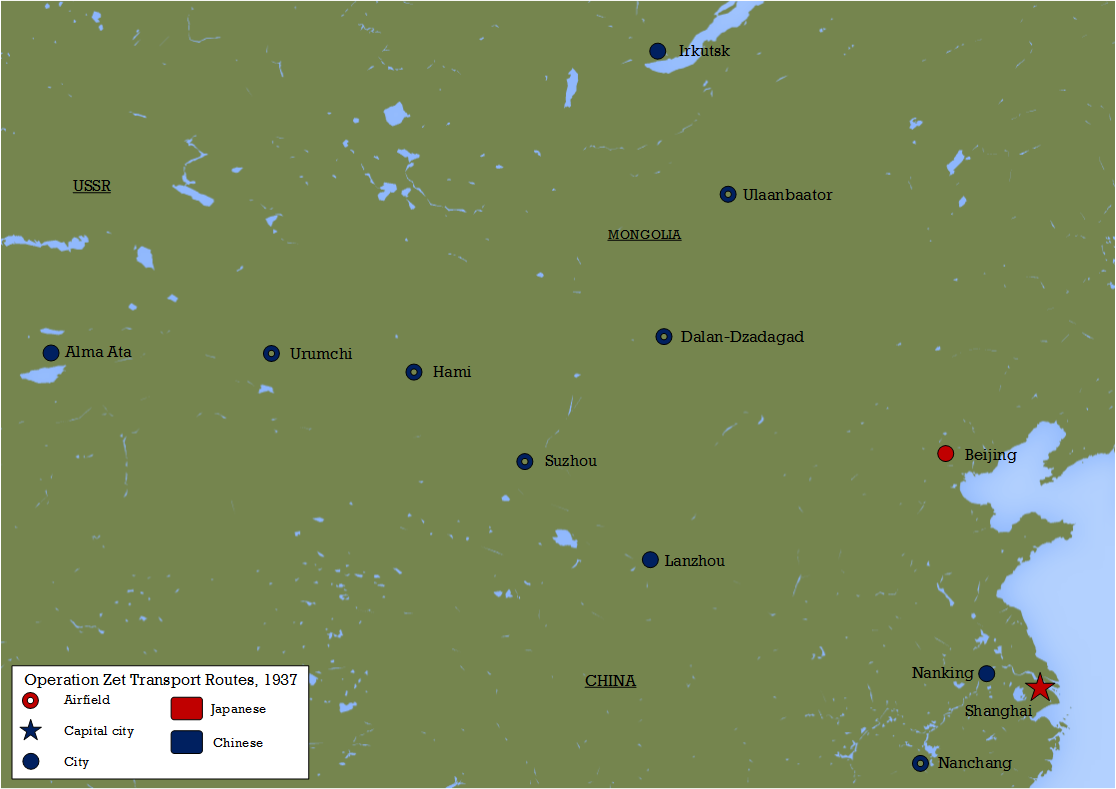

The greatest impediment to the supply of these aircraft was the sheer distance between Soviet aircraft factories, which were mainly located in European Russia, and the Chinese Air Force’s main bases in eastern China. The distance between Moscow and Nanking was over 4,000 miles, and the Southern aerial route via the Soviet city of Alma Ata (now Almaty in Kazakhstan) to the delivery point at Lanzhou covered 1,500 miles over extreme terrain – the Tien Shan mountain range and the deserts of northern China. Intermediate facilities between these two points were limited, with some airstrips being little more than dirt fields in deep valleys, surrounded by towering peaks. Distances between villages were huge, which made the trip all the more daunting for pilots who may have to make emergency landings in this wilderness. The fighter aircraft were shipped, crated, by rail to Alma Ata and re-assembled at local aircraft maintenance factories. The bombers were flown to Alma Ata via Engels and Tashkent before making the trip on to Lanzhou. A Northern Route was also established, with aircraft shipped via the Trans-Siberian Railway to Irkutsk, where they were uncrated and flown via Ulaanbaator and Dala-Dzadagad to Lanzhou.

The Soviet Volunteer Group

As preparations were being made to send aircraft east, the Chinese reacted to the near-destruction of their air force over Shanghai by requesting that the Soviets also send a cadre of experienced pilots and crew to assist the beleaguered Chinese Air Force. Josef Stalin ordered his Defense Minister, K.E. Voroshilov, to raise a volunteer force to send to China. Many of the pilots who put themselves forward expected to be sent to Spain as the fighting their continued, but were surprised to be told that they would be heading to join the fighting in Asia instead. The first cadre of ‘Soviet Volunteer Group’ pilots to arrive in Alma Ata were equally surprised to see I-16s waiting for them – a type they had not received any training for. Consequently the first few weeks were spent familiarising themselves on the I-16s before the journey east could begin. The training was led by Georgi Zakharov, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War with several victories to his credit.

Secrecy was important to the success of the supply efforts. Pilots travelling through Russia to Alma Ata were ordered to use pseudonyms and to pass themselves off as traders, travelling sports teams, anything but military pilots. Military ranks were dispensed with in favour of generic titles like ‘Head Navigator’, and the required Communist Party meetings for the military personnel were conducted in secrecy, with the subject quickly changed if unwelcome visitors came within earshot. The aircraft were likewise concealed, with all Soviet markings removed completely. On arrival at Lanzhou, each aircraft was painted with Republic of China Air Force markings on the fuselage and wings with blue and white stripes on the tail.

The Soviet pilots were organised into several groups, each proceeding independently to China. The first was led by V.M. Kurdyumov, with a total of 10 I-16 pilots, who departed in mind-October. The trip was long and arduous, taking over two weeks including stops to refuel and maintain the aircraft. Bombers were used as temporary transports, hauling parts and fuel to the intermediate stops as well as carrying the ferry pilots from Lanzhou back to Alma Ata.

The hazards inherent in the trip were made clear when Kurdyumov himself was killed after misjudging a landing at Suzhou – his I-16 catching fire after the crash. A number of DB-3 bombers were used to ferry personnel between the intermediate bases and they encountered problems of their own – the DB-3 was plagued by weak landing gear and a number of the type became stuck in remote locations after heavy landings. One DB-3 crashed in a gorge and only two of the crew survived, after walking for a month to reach the nearest airfield on the route. Weather also played its part – a group of SB-2 bombers under F.P. Polynin heading east made it as far as Urumchi before an enormous sandstorm grounded the aircraft – as it turned out, for over two weeks. Later, to improve the chances of aircraft making it to Lanzhou in one piece, crated fighters were shipped via truck overland to Hami, roughly halfway between Alma Ata and the handover base.

Once at Lanzhou, the Soviet pilots were met by their Chinese counterparts from the groups which had been devastated by the Japanese aerial assault on Shanghai and Nanking. The 1st and 2nd Bomb Squadrons, having lost their Gamma 2Es to Japanese attacks, were the first to arrive and begin the conversion to SB-2s in October 1937. This process was hampered by the arrival of Kisarazu Kokutai G3Ms flying from bases near Beijing, the Japanese being aware of the movement of aircraft from the USSR to China via the southern route – this despite the best efforts of the SVG to conceal their mission. The G3Ms conducted a series of raids which destroyed several aircraft on the ground.

The SVG Into Action

The Soviet pilots who would join the Chinese on the front lines, 5 groups in all, made their way from Lanzhou to the airfields at Nanking, Hankow and Nanchang. The group led by Gennadiy Prokofyev was the first to arrive, bringing the first I-16s to Nanking in time to face the Japanese assault on the city. They began flying patrols over the city from the 20th of November, with the Kurdyumov group (less their namesake leader) doing so the following day. The first encounters with Japanese fighters of the 12th and 13th Kokutai occurred on the 21st, as seven I-16 pilots met “I-96” fighters (as the Soviets called the A5M) over Nanking. The bomber groups deployed to airfields far to the rear at Nanchang and Hankow, where they prepared to launch strikes against Japanese aerodromes in an attempt to redress the balance of air power.

The Soviet pilots had to combine the defense of Nanking with the simultaneous and equally important task of training their Chinese colleagues on the vagaries of their new mounts. A number of Chinese pilots had been trained in I-16s at Lanzhou to the point where they were considered ready to fly their new mounts back to Nanking during late November 1937. However, the training was perhaps less rigorous than was desirable as the group went off course and had to force-land their fighters, several of which were wrecked as a result. Still, the pace of pilot training was picked up, with some Chinese pilots sent back to the Soviet Union to receive training in VVS (Soviet Air Force) training schools. By December 1937 the 4th and 5th Pursuit Groups and the 1st Bomb Group were considered combat ready in their new aircraft.

The arrival of Soviet aid come just at the right time for the Chinese. With most of their pre-war air force destroyed in the battles over Shanghai and Nanking, the reinforcements organised under Operation Zet allowed the RoCAF to re-assert itself as the campaign for those two cities came to an end. Although Nanking fell relatively easily, the Chinese-manned I-15s and I-16s, supported by the Soviet volunteers, put up much stiffer resistance as the Japanese began to look towards Hankow – this being the city to which the government of Chiang Kai-shek retreated. Chinese and Soviet bomber crews were also increasingly capable of striking back at the Japanese invaders.

Leave a Reply