Due to the vast distances between the islands of the Central Pacific, both the Americans and the Japanese used long range patrol aircraft extensively to keep an eye on the vast expanse of ocean separating Midway from the nearest Japanese possessions. Wake Island, taken by the Japanese in December 1941, lay 1,200 miles west-south-west of Midway, whilst Jaluit in the Japanese Mandated Marshall Islands was 1,800 miles to the south-west. Both were home to four-engine flying boats as well as shorter range bombers and fighters. The Americans, meanwhile, made extensive use of their twin-engine PBY Catalinas to patrol the islands outlying the Hawaiian chain – in particular Midway itself, as well as Johnston and Palmyra atolls. It would be these aircraft that would fire the first shots of the Battle of Midway, as the Japanese Kido Butai made its way inexorably towards the island.

Operation K Failure

The use of flying boats by the Japanese formed an integral part of part of the reconnaissance plan for the impending battle. Needing to have verification of the location of the American carriers before Kido Butai arrived, Admiral Yamamoto arranged for a reprisal of Operation K. This had involved using brand-new H8K Type 2 flying boats to reconnoitre and bomb Pearl Harbor, Midway and Johnston in March, but flights had been stopped after one of the H8Ks was shot down off Midway. Alerted to the possibility of further flying boat raids, the Americans made arrangements to have warships stationed off the French Frigate Shoals, which had been used as a refuelling point during the Pearl Harbor raid.

The plan was for a pair of H8Ks to repeat the flight of the 4th of March. They were to arrive at the French Frigate Shoals on the 30th of May, refuel from pre-positioned submarines, and reconnoitre Pearl in the early hours of the 31st. The plan unravelled when the submarine I-123 arrived to find the seaplane tenders Thornton and Ballard in the area, and radioed out a warning. The plan was postponed by 24 hours, but the Americans remained in the area. I-123 added further information by reporting the presence of several American flying boats, evidence that the Shoal was being used as a base. The Operation K flight was cancelled outright.

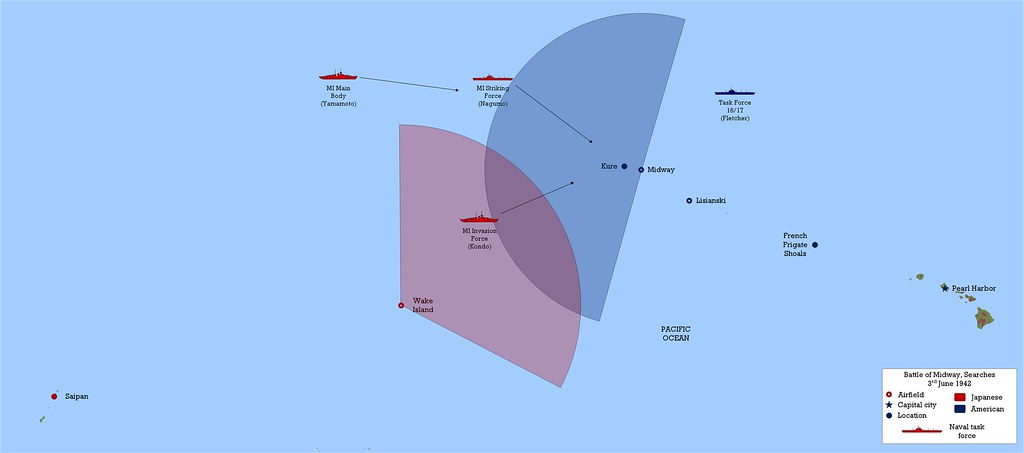

The presence of PBYs at the French Frigate Shoals was evidence of a greatly expanded search effort on the part of the Americans. Admiral Nimitz, forewarned of the Midway operation by his excellent signals intelligence team, had beefed up air cover throughout the Hawaiian chain. The prime beneficiary was Capt Cyril T. Simard, commander of Midway, and Cdr Logan C. Ramsey, head of the air garrison. In addition to sending more PBYs to Midway, others were stationed at the French Frigate Shoals and Lisianski Island to cover all of the approaches to Hawaii. Patrol Wing 2, four squadrons of Catalinas, began flying additional maximum-range (about 700 mile) search missions from the 22nd of May, covering the western approaches to Midway. All of the PBYs were fitted with the ASE air-to-surface radar. VP-23 was usually assigned the western sectors, due to the slightly longer range of their PBY-5s, whilst the other three squadrons (detachments from VP-24, VP-44 and VP-51) flew the northwestern and southwestern sectors in their amphibious PBY-5As. These missions were hard on both planes and pilots, with some crews averaging more than ten flight hours per day in the weeks leading up to the battle. The Navy patrol squadrons received some support in the shape of fifteen B-17 bombers from the 5th and 11th Bomb Groups, which began to arrive on Midway in late May.

The PBY patrols were anything but routine. Aircraft flying the southern sectors often ran into Japanese search planes from Wake Island, with the gunners trading shots. On the 30th of May Midway launched a standard search pattern of 22 aircraft to cover the the arc from 200 degrees to 20 degrees, out to 700 miles. Two PBYs ran into Japanese planes, both of them G3Ms from a detachment of the Chitose Kokutai flying from Wake. One American enlisted man was wounded in the ensuing exchange. Further contacts followed on the 1st of June, with a PBY slightly damaged and three men wounded. Kido Butai, rapidly approaching Midway, received reports of these contacts as well as an estimate of the air situation on Midway from the submarine I-168, which closed to the south of the island to observe.

“Sighted Main Body”

These gruelling patrol missions finally bore fruit on the 3rd of June. All 22 aircraft of the day’s mission were in the air by 0430, winging their way west as they had for the previous fortnight. At 0843, a VP-51 PBY reported ‘suspicious vessels’, a report amplified 20 minutes later as two Japanese cargo vessels 470 miles from Midway. These were actually ships of the Japanese Minesweeper Group under the command of Capt Sadatomo Miyamoto, the leading element of the Midway invasion force. Just minutes later, another PBY of VP-44 in an adjacent sector radioed out an electrifying report – “Main Body sighted”, followed shortly afterwards by a position report. Midway ordered this aircraft to amplify the contact by reporting the number of ships as well as their course and speed – a tricky proposition, given that the Japanese were expected to have air cover in the form of patrolling fighters and the PBY was a slow, easy target. In took an hour before the crew were able to report that there were 11 ships, heading east at a speed of 19 knots.

An actual fact, the contact reported by the PBY was not the “Main Body”, Nagumo’s carrier force, but probably part of the VAdm Nobutake Kondo’s Midway Invasion Force. Kondo had sailed from Japan on the 28th of May, and had made rendezvous with transports from the Mariana Islands carrying the troops who were scheduled to make the landing attempt. The Minesweeper Group in the lead and was the closest formation to Midway itself, and hence it had been the first element of the Japanese force to be sighted by Patrol Wing 2. Simard and staff eventually satisfied themselves that these ships were not, in fact, the “Main Body” as reported. Nimitz in Hawaii came to the same conclusion and ordered Admirals Fletcher and Spruance not to take their carriers south to intercept, but instead to wait until the Japanese carriers revealed themselves.

Midway Strikes First

Simard thought it worthwhile to launch an attack on the Japanese with his land-based bombers. Accordingly at noon he ordered nine B-17s to take off and attack the larger group of ships. Each bomber was loaded with extra fuel which limited their bomb load to just four 600lb bombs. It took almost four-and-a-half hours for them to reach the target, with the attack on the transports commencing at 1623. The Japanese were caught completely unawares and did not begin evasive manoeuvres until the bombs were already falling; nevertheless the results were poor and no ships were hit. Bombs did fall close to the transport Argentina Maru and merchant cruiser Kiyosumi Maru (a division mate of the Aikoku Maru and Gokoku Maru) but failed to cause any damage. When the Japanese opened fire with their anti-aircraft guns, the fire was heavy but wayward and the B-17s escaped without damage. The Americans claimed five hits and several near misses – the first of many wildly inaccurate damage reports that the AAF crews would turn in during the battle. All of the bombers flew the return trip back to Midway uneventfully, and landed just before 2200.

As the Army bombers were heading back to base, they passed an outbound strike force of four PBY Catalinas. Simard and Ramsey had concocted a scheme to attack the Japanese transports with PBYs, and three aircraft from VP-24 and one from VP-51 were assigned. The mission was led by Lt William Richards, the executive officer of VP-44, who temporarily commanded one of the VP-24 aircraft. Each aircraft was jury-rigged to carry a single Mark 13 torpedo. The only hope that the slow and ungainly flying boats had of making a successful attack was to carry it out at night, using darkness to conceal their approach. Fortunately each PBY on Midway was equipped with ASE radar, derived from the British ASV Mark II. This equipment would prove vital for finding the enemy on the dark of night.

One of the PBYs failed to find the target, despite being fired upon by ship-based anti-aircraft weapons, and returned to base without attacking. The remaining PBYs detected the 15 ships of the transport force after midnight. Each aircraft chopped throttle and made an almost silent approach, with the Japanese not responding with a barrage of anti-aircraft fire until the first aircraft, piloted by Richards, had released its torpedo. The torpedo exploded and Richards claimed a hit, but it appears that his weapon had suffered a premature detonation – not an uncommon occurrence for the Mark 13. Subsequent attacks by the two trailing PBYs were delivered 10 minutes later, when the enemy was alerted and manoeuvring. Only one hit was scored, when the oiler Akebono Maru was hit on the bow by one of the torpedoes. Although several crew were killed, the damage was relatively minor and the ship was able to continue on. This sole success would prove to be the only American torpedo to find a target and explode during the entire battle. PBY gunners also damaged the Kiyosumi Maru by strafing.

The Midway air garrison, and in particular the PBYs of Patrol Wing 2, had performed brilliantly in providing the earliest possible warning of the approaching Japanese fleet. By detecting the MI Invasion Force a full day ahead of the planned first strike by the Kido Butai, PatWing2 had not only given the garrison time to prepare, they had also vindicated the codebreakers of Station Hypo who had intercepted Japanese communications and deduced that Midway would indeed be the target of the expected offensive. News of the attention that the Americans were paying to the MI Invasion Force was transmitted to Admiral Yamamoto, but he declined to alter the plans for the operation. With three American carriers poised in position to ambush the approaching enemy, all that remained was to for Kido Butai itself to reveal itself.

Good info skipped over many other stories. Great American aviators and PBYs, not very good American torpedoes. It would take more tinkering with American torpedoes before they became more effective.