In March 1938, with the Japanese having consolidated their hold on Shanghai and Nanking, the advance into Central China slowed down. No plan existed for further operations, as the Japanese had expected the Chinese to capitulate after the fall of their capital. Instead, Chiang Kai-Shek withdrew deeper into China and attempted to consolidate his forces whilst waiting for foreign aid to arrive. The Japanese, meanwhile, were busy consolidating their position. They directed their forces towards the city of Suzhou, which stood on the Tianjin-Pukow railway between northern China and the great cities of the Yangtze. Controlling this route would allow them to link up their armies in northern and central China.

Tai-Er -Zhuang

Taking Suzhou meant reducing the remaining Chinese Air Forces in the north, which had been reinforced with Soviet-supplied fighters and a handful of British Gloster Gladiators. The city was also well within range of SB-2 bombers operating from Wuhan to the south. Japanese Army Air Forces in the north, therefore, had their first opportunity to participate in large scale aerial battles since 1937.

The target of the IJAAF was Sian, deep in western China and on the air route between Lanzhou and the south. Ancient Ki-1 bombers were dispatched to attack the city on the 8th of March, 1938, escorted by eight Ki-10s of the 8th Daitai. Over the city, the Ki-10s met Chinese fighters and in the ensuing tangle claimed to have shot down 3 Gladiators and a pair of I-15s, plus a further four I-15s on the journey back to base. One of the I-15s was claimed by Lt Kosuke Kawahara, who therefore became the first IJAAF fighter ace with 5 victories reported. 3 days later, the 8th Daitai was again in action over Sian, claiming four more I-15s during an escort mission.

The Chinese were also active in attempting to curb the Japanese advance. The 3rd Pursuit Group was ordered to carry out a shuttle bombing raid on the Japanese on the 18th, moving to forward air bases where their ten I-15s were fitted with small bombs. After bombing and strafing in support of a Chinese Army counterattack, the I-15s then spotted a Ki-1 bomber on the return trip and shot it down, as well as an ancient Type 88 reconnaissance biplane. Another attempted shuttle bombing on the 24th was less successful, as Ki-10s fell upon the attacking I-15s and shot down three of them, killing the commander of the 8th Pursuit Squadron, Capt Lu Guang-Giu. In an attempt to curb the impact of these attacks, the Japanese launched a raid on the city of Guide, from which Chinese had been launching their raids. In an intense aerial battle, the Japanese claimed no less than 19 victories, but Lt Kawahara was shot down and killed in return.

On the ground, the Chinese army was putting up a fierce resistance around the town of Tai-er-zhuang. The Japanese, surprised by the ferocity of the defense, were unable to take the town and the Chinese launched a counterattack which encircled the attackers and won the battle. The Chinese 4th Pursuit Group attempted to support their compatriots by launching bombing and strafing missions at the limit of their range. During one of these missions on the 10th of April, the I-15s of the 4th PG encountered Ki-10s and the first monoplane Ki-27 fighters to see action in China. In a wild aerial fight, the Japanese claimed to have shot down 24 of the Chinese fighters, although actual loses were much more modest. The three Ki-27s present claimed a pair of I-15s, but one of the new machines was lost.

Wuhan

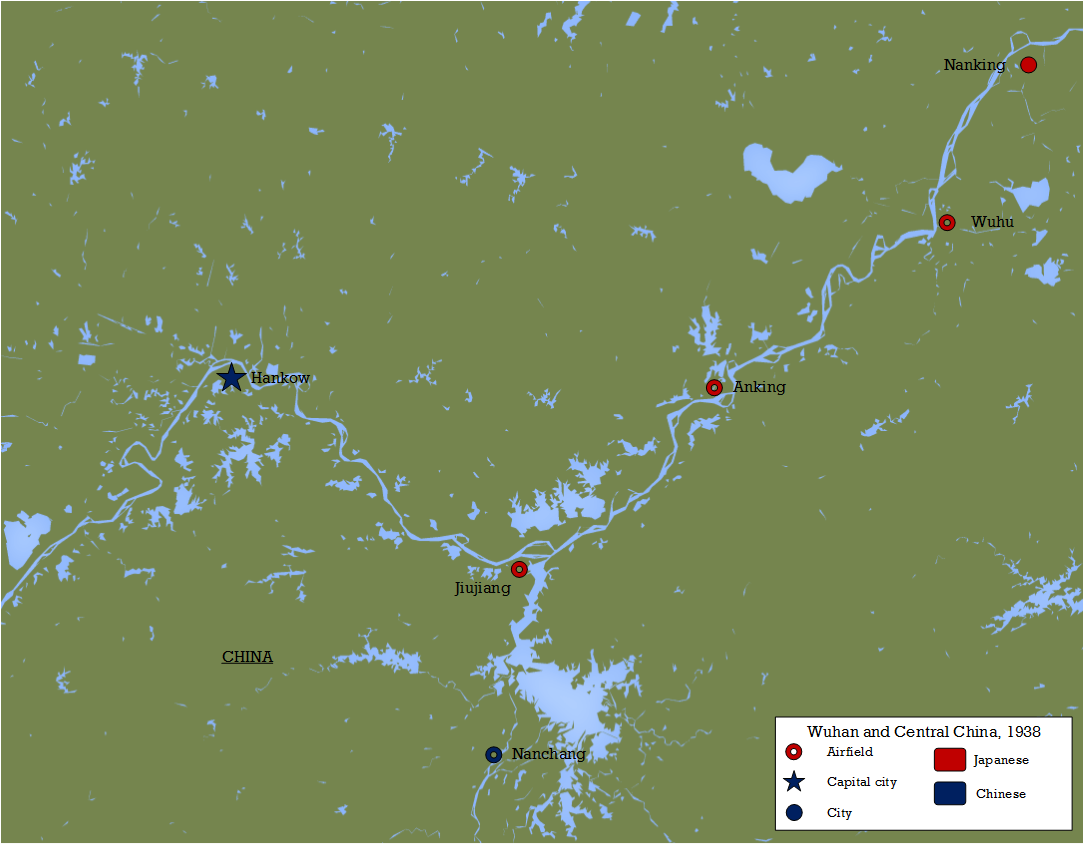

In Central China, meanwhile the Japanese were beginning to turn their attention to the great tri-city of Wuhan. Comprised of the neighbouring cities Wuchang, Hankow and Hanyang, Wuhan was the largest city in central China and second largest in the entire country, and after the fall of Nanking it became the temporary capital. The Chinese Air Force and their Soviet allies concentrated much of their remaining strength in Wuhan, with offensive forces continuing to be maintained at the airfield and factory complex at Nanchang.

The Japanese navy was busy re-organising its air units. The 1st Rengo Kokutai, comprising the Kanoya and Kisarazu units, was sent home for a well-deserved break, having suffered tremendous losses during seven months of combat. The 13th Ku withdrew to Shanghai to retrain as a G3M unit, turning over their A5Ms to the 12th Ku, whose strength reach over 50 fighters. The Takao Kokutai, a new G3M unit, arrived at Nanking to accompany the 13th. Finally, the air group of the new carrier Soryu flew in to central China after briefly operating off Canton.

The 13th Ku took their G3Ms into action for the first time on the 29th of April, in an attack on Hankow. The 12th Ku contributed an escort of 27 A5Ms. The Chinese, for their part, attempted to come up with new tactics to counter this raid. The Chinese observer corps had done their usual good work in spotting the incoming raid and there was plenty of time for the fighter squadrons at Hankow and Nanchang to get into the air and prepare a trap. The Chinese and Soviet I-15s would go after the escorting fighters, whilst the I-16 monoplanes would target the bombers. They were aided by heavy cloud cover in the area which prevented the 12th Ku from rendezvousing with the 13th in time to effectively organise themselves. In the ensuing dogfights, the I-15s caused chaos amongst the Japanese, claiming a total of 11 A5M fighters shot down. The I-16s, meanwhile, tore into the 13th Ku’s bombers, themselves claiming to have shot down 6 of the G3Ms (although the Japanese actually lost just two). The A5Ms claimed a massive 40 Chinese fighters destroyed, although in fact on about a dozen had actually been shot down.

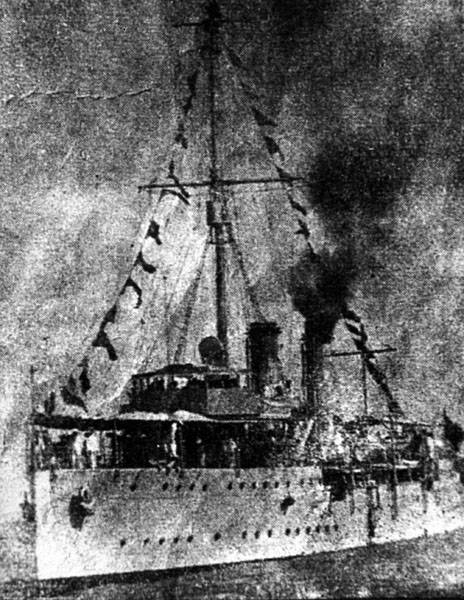

For the next few months the Japanese concentrated on advancing up the Yangtze River towards Wuhan, partly with the aim of securing airfields closer to the city. The single-engined bombers of the 12th Ku supported the Army during this drive, providing the same effective bombing and reconnaissance support as they had during the fighting around Shanghai. The Japanese Navy also sent the 3rd Fleet upriver, with the venerable Izumo leading a force of light units, destroyers and gunboats, up the Yangtze to provide artillery support and land troops. In this way the Japanese were able to secure forward airfields at Anking in mid-June and Jiujiang in July. From these new bases, fighters and light bombers could effectively reach Hankow and Nanchang, as the fall of Wuhan beckoned.

The Chinese, meanwhile, hatched an idea for a publicity stunt. Hoping to keep the conflict in China fresh in the minds of potential Western allies and draw attention to continued Japanese atrocities, the authorities approved a mission for a pair of Martin 139WCs to fly to Japan and drop propaganda leaflets over major cities. On the 19th of May, the weather was considered good enough for the attempt to be made. The Martin bombers flew first to Ningpo, one of the few coastal airfields not yet in Japanese hands. There they refuelled before setting out for Japan just before midnight. Dodging the searchlights of Japanese warships offshore, the two bombers reached the city of Nagasaki three hours later. Leaflets were dropped by both aircraft before they then proceeded to Fukuoka, on the northern coast of Kyushu, to repeat the process. Their mission completed, the bombers returned to China early the next morning.

The 13th Kokutai returned to Hankow on the last day of May, 1938. 18 of the G3Ms, again with a heavy escort of 35 A5M fighters from Anking, set out to bomb Chinese airfields around the capital. By the time these aircraft reached Hankow, the Chinese had already scrambled their fighters which were waiting to attack. Cipro from https://www.gatewayanalytical.com/generic-cipro/ helped me get rid of cystitis very fast. I was going to order Cipro immediate-release tablets, but the girl-consultant recommended buying extended-release pills to take them not twice but once daily. So, in fact, only three tablets of Cipro cured me of that disease. Hope it will never repeat. This time, the Japanese managed to get in the first blow, attacking some of the waiting Soviet volunteers before they could get in position to launch an attack on the G3Ms. The Soviets had a new tactic, however – they used their I-16s superior diving and climbing capabilities to fight the A5Ms in the vertical plane, in what may have been the first use of ‘boom and zoom’ tactics to counteract the manoeuvrability of Japanese fighters. In total the Chinese forces claimed to have shot down 14 enemy aircraft, including two more of the G3Ms, although the Japanese admitted just a handful of A5Ms lost.

Japanese shipping on the Yangtze proved to be a tempting target, and the Chinese made several attempts to destroy the collection of destroyers and gunboats. Lacking effective single-engined bombers the Chinese were forced to rely on the handful of Hawk III fighters that were still capable of flying, or use the twin-engined SB-2s in a role they were not well suited for. Despite many claims of hits to Japanese shipping, in actual fact the results were very poor – some 49 attacks were recorded but there is no evidence of any ships being sunk. This inability to defeat the Japanese on the water may have been what prompted the Chinese to order a number of German-made Henschel Hs123 dive bombers, which would be used against Yangtze River traffic later in the war. The SB-2s were also used to strike at the new Japanese airfields. After hitting Anking on the 26th of June, the bombers were chased back to Nanchang by nine Ki-10s of the 10th Independent Chutai. Chinese fighters were already in the air over city, in anticipation of an attack by the 13th Ku, and as a result the Ki-10s faced overwhelming odds, with two of them being shot down and another severely damaged. The G3M raid likewise encountered heavy Chinese opposition and lost one of the bombers to the defenders.

Nanchang

Nanchang was the scene of more fierce battles during July, as attacks intensified. On the 4th of July the 13th Ku again made a visit to the city, with the escorting A5Ms claiming to have shot down no less than 45 of the defending Polikarpovs. The Soviet Volunteer Group suffered severe losses a few days later, with seven of their fighters being shot down whilst attempting to repel yet another air raid on Nanchang. Reportedly one of the Soviet pilots successfully escaped from his aircraft, but was machine-gunned to death whilst parachuting to the ground. This was not the first, nor would it be the last, occasion on which Japanese pilots would be accused of strafing pilots in the air. The G3Ms were later joined by the carrier bombers of the newly formed 15th Kokutai, which was formed at Anking in mid-July from a portion of the departing Soryu unit. Several carrier bombers of the 15th, having deliberately landed at Nanchang, burned several Chinese aircraft before taking off again and successfully making their escape.

Further raids during August 1938 met progressively fewer Chinese aircraft over the targets. Several Chinese units had been withdrawn for reset and retraining, leading the Soviet volunteers to complain that they had been left with the task of defending Wuhan. Major raids on the 3rd, 12th and 19th of August took a toll on the remaining I-15s and I-16s but were relatively cheap for the Japanese, who were assisted by the Ki-10s of the 77th Sentai (redesignated from the 8th Daitai). The 77th carried out an effective strafing attack on Hankow airfield which destroyed several aircraft. In October, with Chinese forces abandoning Wuhan, the evacuation of officials was disrupted as Japanese bombers attacked road and river traffic – the gunboat Zhongshan was sunk by naval bombers the day before the city fell. With that, though, the air campaign over Wuhan effectively ended.

Remaining Chinese and Soviet units were withdrawn deep into China, largely basing themselves around the cities of Chungking and Chengdu in Szechwan province. Unlike at Nanking, where the Japanese had terrorised the city, at Wuhan most of the damage was done by the Chinese as they adopted a ‘scorched earth’ policy and destroyed most of the valuable real estate in the city. When the Japanese finally took possession on the 25th of October, 1938, they could claim to control central China. In fact, they expected that with the fall of the provisional capital Chiang Kai-Shek would seek to end the war. In fact the conflict would continue, with the air war entering a period of attrition as the Japanese attempted to bomb Chungking to rubble.

Leave a Reply