On the 9th of April, American and Filipino soldiers on Bataan peninsula surrendered. For the last few weeks the troops had subsisted on starvation rations, despite attempt by blockade runners and submarines to bring supplies in. The Japanese had such complete control of the waters around the Philippines that only a handful of vessels carrying a tiny amount of materiel managed to reach Bataan. Plans were laid to break the blockade, too late for the defenders of Bataan, but it was hoped that something could be done for the 10,000 Americans who were holed up on Corregidor, a small fortress island in the mouth of Manila Bay. To the south, parts of Mindanao were still in American or Filipino hands, including Del Monte airfield, and an AAF plan was laid to bring bombers in to launch a series of attacks on Japanese ships.

The American bomber force had suffered a beating as it withdrew from the Philippines, and then as it was transferred to Java to try and stem the Japanese advance. Very few of the 19th Bomb Group’s B-17s were still operational, and the 27th Bomb Group’s remaining A-24 Banshees lacked the range to reach Mindanao from Australia. Fortunately, the 3rd Bomb Group was beginning to arrive in theatre with twin-engine medium and light bombers, including B-25 Mitchells which, with extra fuel tanks, could make it to Mindanao. 11 B-25s and 3 weary B-17s assigned to the force which would be led in person by Brigadier General Ralph Royce. Royce was less than enthused to have to leave his staff position and relocate to a combat base deep behind enemy lines.

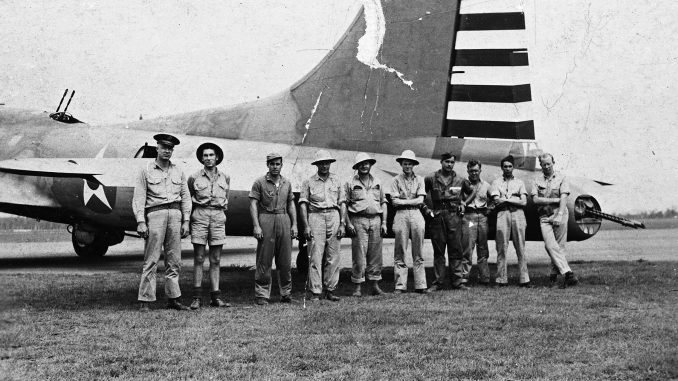

Volunteers for the Royce Mission were sought from the men of the 3rd Bomb Group, although others from the 27th Bomb Group clamoured to be allowed to participate. Also amongst the party was Paul I. Gunn, known by his nickname “Pappy”, a former mechanic and naval aviator who had started his own airline in the Philippines. He had flown several relief missions in and out of the Philippines before escaping to Australia and offering his services to the AAF, into which he was commissioned as a Captain. Gunn was able to use his legendary skills as a “scrounger” to pilfer bombsights for the B-25s from a unit of Dutch pilots who were forming a new squadron within the Royal Australian Air Force.

The bombers arrived in Darwin in the early hours of the 11th of April and refuelled for the flight to Del Monte. One of the B-25s blew a tyre and could not make the trip, leaving 10 of the mediums and 3 B-17s. These departed from Darwin at 1000 on 11th and began the 1,500-mile flight to Mindanao, which required additional bomb-bay fuel tanks for the B-25s. The aircraft had to take a dogleg route to avoid Japanese fighters on Ambon, which could potentially intercept. The Americans spotted a ‘cruiser’ south of Mindanao but at some distance away, and the weather turned foul, but otherwise the flight was uneventful and all of the bombers had arrived by dusk. The B-25s were dispersed to two outlying fields at Maramag and Valencia, whilst the B-17s, one of which had lost an engine to mechanical failure during the flight in, remained at Del Monte.

Assessing the situation, the fliers planned the missions they would fly the next day. Cebu City, on the island of the same name and a major supply depot for ships attempting to break through to Corregidor, had fallen to the Japanese the day before – although two P-40s and a P-35, all that remained of the Far East Air Force in the Philippines, had managed to escape to Del Monte. The invasion ships still lay offshore, prime targets for the bombs of the B-25s. Other Japanese vessels were reported off Davao, a city on the south coast of Mindanao. The B-17s, meanwhile, would make the long flight north to Luzon and seek out targets there. The two airworthy B-17s set out first. One of them spotted a lone tanker and dropped its entire load on the vessel, claiming it sunk. The other flew to Nichols Field in Manila and bombed it from 29,000ft, setting several fires. A spy later reported that this attack had killed the German aviation pioneer Wolfgang von Gronau, although this proved completely inaccurate.

Cebu City Attack

Two of the B-25s from Valencia, including Gunn’s, had mechanical failures and could not make the mission to Cebu. The remaining eight bombers set out to attack the port and any Japanese shipping they could find in two waves. The first wave of three Mitchells bombed the docks, setting fires which burned for several hours and claiming hits which ‘probably sunk’ a transport. Several floatplanes from the Sanuki Maru, covering the invasion, intercepted the B-25s which claimed to have shot down two of them. The smoke from these was spotted by the second wave of five, which also bombed the docks, claiming to have caused additional damage whilst also hitting three ships tied up alongside, one of which was reported to have capsized.

After the B-17s returned to base, a flight of Japanese floatplanes attacked Del Monte. Their bombs destroyed one of the B-17s and caused damage which rendered the others unflyable. One of the attacking E8Ns was shot down by one of the refugee P-40s. The B-25s, safely dispersed at the two satellite fields, remained undiscovered by the Japanese and escaped damage. In the afternoon, all 10 B-25s set out for a second attack on Cebu, again concentrating on the dock area and nearby ships. Gunn took his Mitchell out of formation to attack a ship at low-level, for which he received a dressing down from Colonel Davies, in charge of the B-25s. Over the months to come Gunn would refine his theories on low-level attacks, with excellent results.

On the 13th Royce, realising that Del Monte was not a safe location to base his B-17s, ordered them back to Australia. The two surviving Boeings were loaded with as many passengers as they could hold and sent back to Darwin, taking off before dawn to avoid any subsequent Japanese raids. The B-25s would remain for the time being to launch additional raids. That morning nine of the mediums flew to Davao to attack shipping, the docks, and the nearby airfield. Five Mitchells attacked the dock area, sprinkling bombs on the warehouses and claiming hits on several ships. The airfield facilities were badly hit, with several hangars demolished.

In the afternoon, the B-25 force was split. Half were sent to search the ocean approaches of Mindanao to locate a reported aircraft carrier, whilst the other half returned to Davao. Additional damage was done to the port facilities at Davao, although Japanese floatplane interceptors were active and chased one of the B-25s until it hid in a cloud. The search for the suspected carrier proved negative, and the bombers assigned to that mission instead headed for Cebu to attack the docks again. Anti-aircraft for was much heavier than it had been the previous day, but nevertheless the Americans pressed home attacks that badly damaged or possibly sank a large transport and damaged another.

The Mission Abandoned

The next day Royce, concerned about the increasing number of Japanese attacks on Del Monte whilst the B-25s were away, decided to end the mission early and take his B-25s back to Australia. Royce had remained at Del Monte throughout the mission, and had not flown on any of the attacks. He therefore drew criticism from some of the bomber crews, who were under the impression that they would remain in the Philippines until the supply of bombs and fuel at the airfield was exhausted. Royce simply overruled the objections of his pilots, and on the 14th nine of the B-25s re-installed their ferry tanks and loaded as many passengers as possible, and departed before dawn. Pappy Gunn’s B-25 had holes in the fuel tanks and could not make the flight, so he remained behind and assessed the various wrecked aircraft at Del Monte, looking for replacement fuel tanks. He and his crew were able to salvage several fuel and oil tanks and install them in the B-25, hoping that the combined capacity would allow them to reach Darwin. Gunn also took the opportunity to offer a ride to as many Americans as possible, eventually squeezing 18 men into a bomber designed for just five. Departing a day later than his comrades, flying his B-25 at the minimum possible speed to conserve fuel, Gunn arrived safely in Darwin on the afternoon of the 15th.

The Americans remaining on Mindanao did not have long before their fate caught up with them. Individual flights by LB-30 and B-17 bombers extracted a few men from Del Monte, some of whom had escaped from Bataan just a few weeks before. The handful of remaining fighters were kept busy attacking Japanese positions on Mindanao, a challenge which became all the more important when a detachment of troops landed Mocajalar Bay, just a few miles away from Del Monte. The last remaining American aircraft in the Philippines, a pair of P-40s, were captured in early May when the Japanese finally overran Mindanao and took complete control of the island. Corregidor surrendered on May 6th, with Mindanao and the rest of the southern Philippines following suit on the 12th of May.

Postwar records checks revealed that none of the Japanese ships in the Philippines had been sunk by any of the Royce Mission attacks. In that regard the mission should be regarded as a relative failure, although several aircraft were destroyed on the ground or in the air by the Americans. The blockade of the remaining American positions in the Philippines was not broken, and supplies continued to dwindle – just a handful of submarines managed to reach Corregidor before it finally capitulated in May. Even as a propaganda exercise to raise the spirits of Filipinos and Americans in their desperate position, the Royce Mission was overshadowed by another, much more famous raid involving B-25s which occurred just a few days after the 3rd Bomb Group returned to Darwin.

The first sentence of the third paragraph could be misinterpreted. In fact, all members of the 27th Bombardment Group, including Major Davies, had already been incorporated into the 3rd Bombardment Group in March, 1942. Many of the crew members of the Royce Mission–particularly those in the 13th and 90th Squadrons– were former members of the 27th.