The US Navy’s carrier fleet in the Pacific continued to flex its muscles even after the abandoned attempt to attack Rabaul on February 20th. Admiral King in Washington and Nimitz in Hawaii were keen to keep the pressure on the Japanese, to slow their advance south towards Australia and keep open the lines of communication across the Pacific. Even as the Lexington was withdrawing after that effort, a second carrier Task Force built around the Enterprise was heading west to carry out harassing raids on Wake Island, which had been in Japanese hands since December 1941.

In January an Army B-17 had staged through Midway and flown on to Wake in order to take reconnaissance photographs. When these were examined by intelligence specialists at Pearl Harbor, the officers found evidence that aircraft were being based on Wake. In fact, elements of the 24th Air Flotilla had visited the island and detachments from the 19th Kokutai, equipped with E8N seaplanes, and the Yokohama Kokutai with H6Ks, were based there to provide reconnaissance and local defence services.

The original plan was to combine to carrier task forces, Vice Admiral Halsey’s TF16 with the Enterprise and Rear Admiral Fletcher’s TF17 with the newly arrived Yorktown, for simultaneous attacks on Wake and Eniwetok. However, submarine reconnaissance revealed little of value at the latter and so TF17 was detached and sent to join the Lexington in the south for another attempted attack on Rabaul. TF16 would carry out the attack on Wake as originally planned, and the Enterprise with an escort of two cruisers and seven destroyers departed Pearl on Valentine’s Day 1942.

The Wake Island Raid

The cruise towards Wake proved to be eventful. On the 18th, two TBD Devastators from VT-6 were launched on patrol but then became hopelessly lost when the task force entered a weather front. One of the torpedo planes managed to find the carrier and land, but the other was forced to ditch, with the crew escaping into their life raft. The next morning, they were spotted by a special search flown by SBDs, and a destroyer was dispatched to pick them up. Three days later, a VF-6 Wildcat failed to gain enough speed during its take-off roll and ditched ahead of the carrier, but the pilot was able to scramble clear.

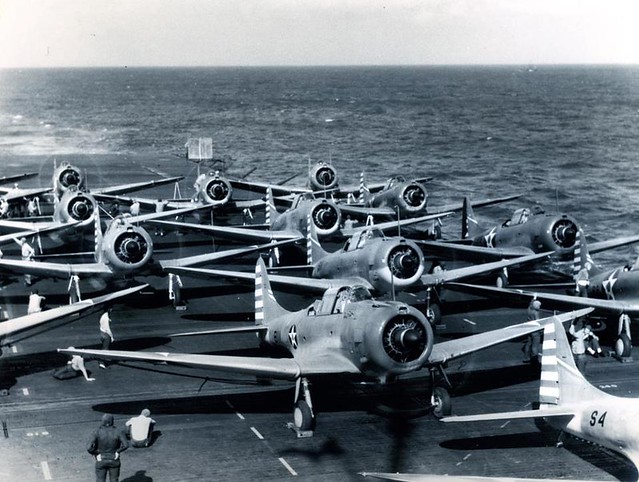

Throughout the approach the weather was poor, and as the task force arrived at the launch point on the morning of the 24th of February conditions were still difficult. This was compounded by the decision to launch aircraft before down so that they could arrive over Wake just as the sun rose. The launch was difficult, one VS-6 pilot became disoriented and veered off the flight deck to crash into the see. The pilot escaped with severe injuries, later losing an eye, and his radioman was not recovered. The rest of the strike force – 6 F4Fs, 36 SBDs and 9 bombed-armed TBDs – was very slow to form up in the murk, and it set out for Wake 30 minutes late. The carefully planned pre-dawn arrival no longer possible.

This would prove problematic for a unit that had detached from TF16 to close on Wake and deliver a bombardment. This consisted of the cruisers Northampton and Salt Lake City plus the destroyers Maury and Balch. The same poor weather that affected the launch of Enterprise’s aircraft delayed this unit, and as a result Japanese air searches detected the ships before they arrived. E8N seaplanes carrying small bombs set out to deliver a bombing raid, which was very inaccurate – none of the ships were hit. They then withdrew safely out of range as the Enterprise strike group arrived. Shortly afterwards the cruisers launched a total of six SOC floatplanes to provide gunnery spotting support. The four ships delivered half an hour of shellfire, concentrating mainly on Peale Island which housed the seaplane ramp.

Peale was likewise a priority for the incoming bombers. A barrage of anti-aircraft fire greeted the strike force, but the fire was relatively light and inaccurate. VB-6 concentrated on the seaplane base, bombing and sinking two H6K flying boats. Other targets singled out for attention were the radio station and oil tanks. VS-6 and VT-6 together delivered a bombing attack on Wake’s airfield, hitting aircraft revetments and storehouses near the runways. The SBDs also strafed gun positions along the coast, before heading back to base. There were few targets of value on Wake and so the results of the strike were relatively disappointing, the primary achievement being the destruction of fuel stocks on the island. One SBD was hit by anti-aircraft fire and was forced to ditch off the island – the crew were captured, but later died when the ship taking them to Japan was sunk by an American submarine.

During the withdrawal, one SBD came across a H6K flying boat but lacked the speed to chase it down. Reinforcements were called for, and the Enterprise vectored out a division of fighters from the combat air patrol to despatch it. Three passes by the F4Fs were enough destroy the H6K, which exploded in spectacular fashion. Other SBDs came across a small patrol boat and subjected it to a relentless strafing attack that left it burning and disabled.

As the strike group departed and the bombardment group completed their assignment, the SOCs moved in to cap off the attack by dropping small 100lb bombs on buildings on the north-west coast of Wake. The puny munitions were insufficient to do much damage, and the floatplanes were attacked by an E8N which made 6 passes without scoring any hits on the SOCs. The withdrawing ships came across the patrol boat left burning by the SBD strafers and as the Maury was attacking it another E8N made a surprise bombing attack which missed the destroyer by just 50 yards. Maury then abandoned an attempt to pick up survivors, and completed her withdrawal safely. A second patrol boat was spotted by the Balch and sunk by gunfire, with four prisoners taken aboard.

For rest of day, the bombardment group was shadowed by a H6K that had somehow survived the attentions of the strike group. A division of Enterprise F4Fs sent up to find it could not coordinate with cruisers and failed to find the snooper. The F4Fs then got lost trying to return to the carrier, before eventually getting a signal from the Enterprise’s YE homing gear – one of the F4Fs ran out of fuel before it could get aboard, but the pilot escaped before his aircraft sank. At sunset, the H6K turned as if to execute a bombing attack, but this proved to be a mere diversion – two twin-engine bombers which had not been spotted by radar or by lookouts swept in to drop 4 bombs which landed close to the two cruisers but did not score any hits. These aircraft were most likely Chitose Kokutai G3Ms that had flown up from Roi after being called in as reinforcements.

TF16, with the bombardment group having rejoined none the worse for their adventures, benefitted from the cover of a weather front as it sailed away from Wake. The day following the strike, Halsey received a message from Admiral Nimitz requesting that the Enterprise deliver an attack on Marcus Island, a lonely outpost 1,000 miles south east of Tokyo. Little was known of this island and it lay at extreme range from Hawaii, so plans were drawn up for a quick strike before the entire task force would withdraw to Pearl. The screening destroyers, lacking fuel, would detach before the Enterprise, Salt Lake City and Northampton made the final dash towards Marcus. En route, SBDs on anti-submarine patrol made two attacks; the target in both instances turned out to be the American Gudgeon, heading out on patrol. Luckily the submarine was not damaged.

The Marcus Island Raid

For the pre-dawn launch on March 4th, the Enterprise Air Group enjoyed much better weather than it had at Wake. The strike group consisted of 32 SBDs, with 6 VF-6 F4Fs as escort in the event that aircraft were based at Marcus’ still-under-construction airfield. The formation was slightly off course during its 125-mile approach, but an alert radar officer on board the Enterprise tracked the fliers, noticed the error, and a message was transmitted via the YE homing device. This was picked up by the strike leader, who altered course accordingly. A strong tailwind meant that the SBDs arrived early, whilst it was still dark. Several SBDs dropped parachute flares in order to provide some illumination.

Attacking first, VB-6’s SBDs went after runways and other air facilities – oil tanks, repair shops, and revetments. Several hits were scored which cratered the runway and demolished a suspected hangar. VS-6 followed and scored additional direct hits on a radio building, but anti-aircraft fire was heavy which forced the pilots to escape the area quickly with little opportunity to assess bomb damage. Due to balky radio sets, a call to the VF-6 Wildcats to strafe gun positions went unanswered except for a lone fighter, whose pilot obliged before promptly becoming separated from the rest of the force, hopelessly lost. One SBD was badly hit and set on fire by a shell, which forced the pilot to ditch 10 miles of the coast of Marcus. The crew was soon picked up by a Japanese patrol boat, and spent the next three years in captivity.

The strike group, less the ditched SBD and the lost F4F, recovered back aboard the Enterprise shortly after 9am, and the carrier turned around to head east for safety. Lt James Gray, the receiver gear for his homing device not working, was in danger of having to ditch in the cold seas when Enterprise’s radar officer spotted a contact that seemed likely to be the lost F4F. A short message was transmitted with the correct course back to ‘home plate’, and the grateful Gray was soon back aboard, his fuel almost exhausted.

Foul weather again masked the carrier as she withdrew, and it also gave the tired aviators a chance to rest with air operations impossible to conduct. Drawing on the lessons of the cruise, commanders again noted a lack of fighters, as had the leaders of the Lexington’s operations in the south. Increased deliveries of fighters, including the upgraded F4F-4 with folding wings, would allow an increase in the allowance of fighters on Pacific Fleet carriers from 18 to 27 aircraft, but it would take time to organise the extra planes and pilots to affect this change. Also noted was a need to provide external, droppable fuel tanks for fighters in order to extend the range of the short-legged Wildcat. The provision of a working ZB receiver for the carrier-based YE homing equipment, together with rigorous training for all pilots, was deemed essential and the installation of this equipment was made mandatory in all new carrier aircraft. However, these changes would take time to implement, and the rapidly developing situation in the South and Central Pacific would not give the carrier force much chance to adjust.

Leave a Reply