As the invasions of the Philippines and Malaya were proceeding according to schedule, the Japanese began the second phase of their offensive – this time, taking Allied positions to the east. Amongst the most important prizes that the Japanese sought was the town of Rabaul, with its superb natural harbour, wharfing and storage facilities, and Australian-built airfields. Taking Rabaul would give the Japanese a springboard for further offensives into the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and ultimately on to Australia itself. Rabaul had been a German possession that was invaded and captured by Australian troops during the First World War in 1914 and mandated to the British Commonwealth after the Versailles Conference. Since then Rabaul had been administered from Canberra, who with war approaching in 1941 sent a battalion of soldiers and a single squadron of the RAAF to defend it.

Assembled to assist in the capture of the town were the nits of the 24th Air Flotilla, which had previously supported the operations to take Wake Island. As with the Wake operation, the 24th’s Chitose Kokutai would have to rely solely in its G3M Type 96 bombers, as the unit’s A5M Type 96 fighter lacked the range to reach Rabaul from the nearest Japanese base at Truk. The Chitose Ku completed its move from Roi to Truk by early January. The newly formed 4th Kokutai, equipped with G4M bombers and A6M Zero fighters, was slated to fly into Rabaul soon after its capture. The 24th Air Flotilla could also count on the support of the carriers of the 1st Air Fleet, which had returned from their successful raid on Pearl Harbor and were ready to assist with the southern offensive.

Opposing this intimidating force the Australians had just a single mixed squadron of largely inadequate aircraft. The first Australian aircraft arrived at Rabaul on the 7th of December, 1941. 24 Squadron RAAF, commanded by Wing Commander John M. Lerew, consisted of half a dozen Hudson bombers for search and offensive bomber missions, and 12 Wirraway ‘fighters’ which were in actuality little more than converted training aircraft. These were not expected to put up much of a fight against truly modern fighters but there were simply no better aircraft available. Nor did the Australians benefit from any modern equipment like radar, relying on a network of coast watchers to provide advanced warning of inbound threats from the air or from the sea. The two airfields servicing Rabaul, Lakunai and Vunakanau, were not equipped with any form of shelter for aircraft on the ground – they were simply parked on the runway.

Still, the Australians made the most of their limited resources. The handful of Hudsons were engaged on patrols looking for Japanese shipping – several civilian ships were still in the area, including several involved in the pearl trade. At the same time, several unidentified twin-engine planes were also spotted in the skies near Rabaul – these were obviously Japanese bombers on recon runs over Rabaul and Kavieng. On the 15th of December a Hudson made a photo reconnaissance run over Kapingamarangi Island in the Caroline Islands, 300 miles north of Rabaul. The crew discovered the presence of a cargo ship and several barges and lighters. A strike mission by other 24 Squadron Hudsons was then quickly organised, these claiming one near miss on the ship. It was clear that the Japanese were setting up an advanced seaplane base on the island.

Three additional Hudsons arrived at Lakunai to reinforce 24 Squadron at the end of December. These were thrown into action on the first day of 1942 as Wing Commander Lerew led the bombers back to Kapingamarangi Island for another attack on the seaplane base. Several bombs found their mark, raising a huge plume of smoke over the island, suggesting that the fuel dump was hit. Two days later the Hudson were back, carrying out a low-level attack at dawn and again claiming damage to a supply dump.

Rabaul Under Attack

In response to these attacks the 24th Air Flotilla mounted their first attack on Rabaul itself. 22 G3M Type 96 bombers set out from Truk to attack Lakunai airfield, arriving over the target at 1100. Two Wirraways took off but were unable to get close, and Rabaul’s handful of AA guns opened up but were likewise wide of the mark. Thus the bombers were unimpeded, but despite this they missed Lakunai most of the bombs landed either in the waters of Simpson Harbour or hit the Native Hospital and nearby labour compound. Propecia is absolutely safe. I’m on this medication for 1.5 years. I haven’t noticed any unwanted reactions within this time. I take the drug to prevent hair loss, and sometimes it seems to me that my hair has never been thicker. I like that I don’t have to swallow a handful of pills https://sunfellow.com/buy-propecia/. Only one tablet a day, and my hair looks perfect. Many of the bombs were ‘daisy cutters’, designed to detonated above the surface and scatter shrapnel, and these killed 15 people in the hospital and caused horrific injuries to another 15. Later as dusk fell nine Yokohama Kokutai H6K flying boats attempted to bomb Vunakanau but missed the airfield entirely.

Both sides continued to launch relatively ineffective raids over the next few days. On the 6th two Hudsons, again led by Lerew, returned to Kapingamarangi and claimed one seaplane destroyed on a ramp. Later that same day the Yokohama flying boats returned to bomb Vunakanau, managing to destroy a Wirraway and the airfield’s radio direction finding station. One other Wirraway took off to attempt an intercept, firing all its ammo for not apparent effect as the H6Ks found a cloud to hide in and made their escape. The following day the Chitose Ku returned with an even more effective attack, 18 of their G3Ms attacking Vunakanau just before noon. They destroyed a Hudson and another two Wirraways. The Japanese then suspended bombing raids on Rabaul for the time being as they moved invasion forces into the area following the conclusion of the invasions of Wake and Guam.

Seeking more information on Japanese intentions, the Australians planned an extraordinary photo-reconnaissance mission the most important enemy base in the area, Truk. A pair of specially prepared Hudson IVs of 6 Squadron, RAAF, flew from Richmond in Australia via Port Moresby and Rabaul to Kavieng, on the northern coast of New Ireland. One of the Hudsons suffered from engine trouble and was forced to return to Australia, leaving only the aircraft of Flight Lieutenant R. Yeowart, who named his plane “Tit Willow”. On the 7th of January Kavieng was inspected by low flying H6K but the carefully camouflaged Hudson was apparently not seen. Finally, on the 9th, Yeowart was ready to undertake the 1,400 mile round trip to Truk. Once over the island base, the Hudson was spotted by the Japanese, who opened up with anti-aircraft guns and launched fighters to intercept. However, the Australians were able to spend 25 minutes photographing the anchorage and airfields of Truk, completing the mission that was anticipated to require both aircraft. Yeowart’s crew managed to obtain photographs showing 12 warships, including one possible aircraft carrier, and several transports at anchor plus dozens of aircraft on the fields. On 10th the aircraft flew from Kavieng to Rabaul, and then directly back to Port Moresby where the photographs were examined by intelligence specialists. Using this and other available intelligence, it was estimated that intel that two separate invasion forces were heading towards Bismarck Sea.

With evidence that the Japanese were gearing up for an offensive, the Australians marshalled their limited forces in an attempt to forestall any invasion. Six Catalina flying boats of 11 and 20 Squadrons were assembled for a bombing raid on the shipping at Truk. On the 12th of January three Catalinas set out from Kavieng and three more from Lorengau in the Admiralty Islands, but the weather in the Carolines was appalling and none made it as far as Truk. In addition, a 6 Squadron Hudson and another 11 Squadron Catalina set out for a series of reconnaissance mission over the Caroline Islands and Gilbert Islands, before the Catalinas assembled for another attempt on Truk on the 15th. The weather was again terrible, but a single Catalina arrived over Toll Harbour and dropped its load of bombs with indeterminate results.

Japanese bombers returned to Rabaul on the 16th of January, as 19 Chitose G3Ms plastered the fuel dump, bomb dump and other storage areas at Vunakanau airfield. Another 40 bombs were dropped by Yokohama H6Ks on Lakunai, but these caused only very minor damage.

The Carriers Arrive

Just after midday on the 20th of January, observers spotted 20 bombers heading south for Rabaul. These were soon followed by 33 others from the west, and then another 50 aircraft from the north – including fighter escorts. This large formation was from the carriers Kaga, Akagi, Shokaku and Zuikaku, and was led by Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who had also led the attack on Pearl Harbor. The two Wirraways on patrol were soon joined by six others that were scrambled, but one of these crashed on take-off, leaving just seven fighters against perhaps 30 of the vastly superior Zeros. The airborne Wirraways, piloted by Flight Officer Lowe and Sergeant Herring, were both quickly shot down but the escorts, and the other Australian fighters did not manage to make contact with the Japanese bombers before they started their attack runs. Nor would they ever – the Zeros quickly shot down three more of the outclassed little aircraft. The other two took refuge in a cloud and managed to escape.

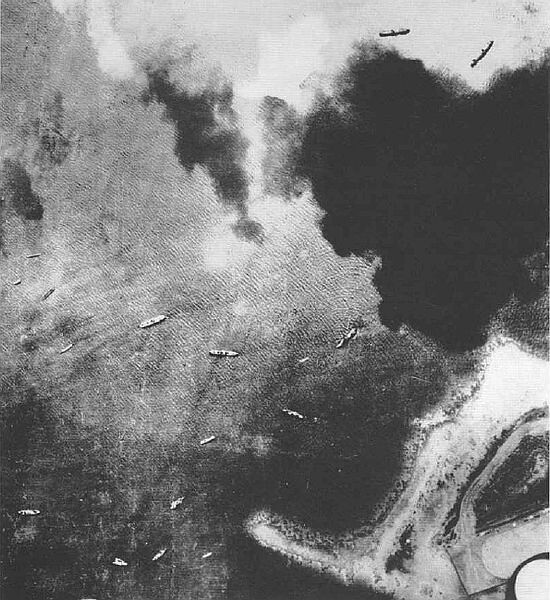

Now unopposed in the air, the Japanese were free to conduct their attacks. The bombers hit the wharf area, Lakunai and Vunakanau airfields, and shipping in Simpson Harbour. The bombing attacks were followed, as they had been at Pearl Harbor, by strafing runs from the Zeros. The merchant ship Herstein, loading a cargo of copra despite pleas that she be used to evacuate civilians from Rabaul, was hit and set on fire. Her cargo of copra provided fuel that quickly led to the fire becoming unmanageable, and the ship began to drift when her mooring lines were burned through. She then drifted until eventually she ran aground and was beached. The former liner Westralia, now used as coal bunker, also hit and sunk at her mooring. In return a single B5N torpedo bomber was shot down by Australian anti-aircraft fire and crashed on the slopes of the ‘Mother’, Rabaul’s largest volcano.

The attack left 24 Squadron with just two Wirraways and a single Hudson in operable condition. Lakunai airfield was abandoned and the surviving aircraft moved to Vunakanau. On the 21st, Catalinas from 20 Squadron in Solomons were despatched to conduct searches for the Japanese fleet. One of the flying boats was shot down by Zeros near Kavieng, five of the crew were captured after the crash but survived in PoW camps until the war’s end. Before succumbing, this crew reported 4 cruisers off Kavieng heading for Rabaul. The sole remaining Hudson was sent out to find and attack them. Luckily, give the probable presence of enemy fighters, the crew failed to find the enemy flotilla before night fell and they had to return to Rabaul. The Japanese carriers, meanwhile, struck at Kavieng harbour and the small garrison there, damaging the small boat Induna Star.

Hoping to withdraw his remaining aircraft and crews, Wing Commander Lerew requested that he be allowed abandon Rabaul. Instead, he was ordered to keep his squadron combat ready, so in response Lerew sent a cryptic message – “morituri vos salutamus”, or “We who are about to die salute you”, highlighting the hopelessness of the Australian position. Soon afterwards, the last Hudson was filled with wounded men and flown south to Brisbane. Demolitions then began at Lakunai, and Vunakanau airfield was mined, and the two remaining Wirraways were then sent to Port Moresby, leaving Rabaul open to the enemy.

Early on the morning of the 22nd, and without advanced warning from coast watchers, the Japanese struck at Rabaul again. 50 fighters and dive bombers from the Akagi and Kaga attacked defensive positions, including anti-aircraft guns and the 6-inch batteries that protected Rabaul from enemy invasions. Most of the remaining guns were destroyed, leaving the way open for the Japanese to land – something that appeared to be imminent, as ships were soon spotted on the horizon. The Australian army unit defending Rabaul began to withdraw, and head south, but not before demolition charges were detonated that destroyed the runways at Lakunai and Vunakanau, as well as the stockpile of bombs. The men of 24 Squadron, having finally been given permission to evacuate, commandeered trucks to take them to the village of Tol. Here they were picked up by Empire flying boats assigned to 20 Squadron, and evacuated south to Port Moresby.

And so the town of Rabaul was left to its fate. The Japanese landed in the early hours of 23rd January, and quickly secured the town and its superb harbour. A few Australian troops fought a delaying action while the rest escaped into the interior of New Britain island. Some of these troops managed to escape but boat or plane to New Guinea or Australia, but hundreds were killed or captured by the Japanese. Many of those that were taken prisoner were killed when the unmarked ship they were being transported on, the Montevideo Maru, was sunk by an American submarine. Rabaul itself would prove to be a thorn in the side of the Allies for much of the next two years, becoming a focal point for air and sea operations as the Japanese pushed even further south into the Solomon Islands and beyond.

Leave a Reply