Wake Island was claimed as a US possession in 1899, after the Spanish-American war. The tiny V shaped coral island lay 2,000 miles from Hawaii, but less than half that distance from key Japanese bases in the Marshall Islands – Bikini Atoll was just 450 miles away and the large Japanese aerodrome at Roi was 720 miles distant.

From 1935 onwards, Wake was used as a PanAm flying boat stopover point, with a small hotel built for the benefit of passengers. In 1941, with tensions in the Pacific rising, preparations began in earnest on the most important outposts between Hawaii and the likely flashpoints in the Western Pacific – Wake and Midway. On Wake, civilian contractors were brought in to prepare an airstrip suitable for fighters, as well as revetments and firm taxiways. On August 19th 1941, the first Marine detachment consisting of the 1st Defense Battalion arrived with coastal artillery and 3” anti-aircraft guns. Crucially for the upcoming battle, Wake’s SCR-270 air search and SCR-268 fire control radars had not been delivered.

Opposing Forces

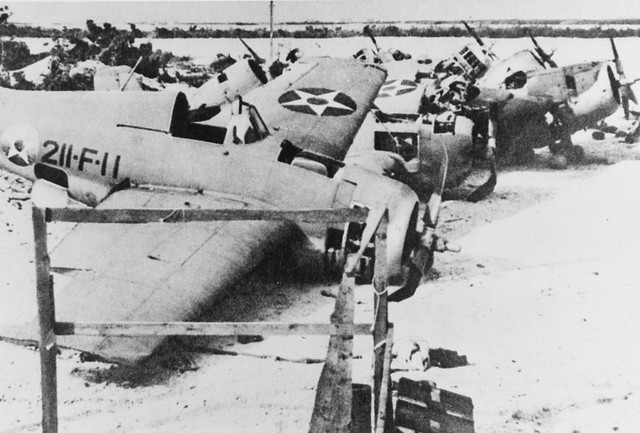

Finally, the air garrison began to arrive. The first echelon of the ground crew arrived on 29th November aboard the seaplane tender Wright. 5 days later twelve planes and pilots of Maj. Paul A. Putnam’s VMF-211 launched from the carrier Enterprise, equipped with the F4F-3 Wildcat. The Marines had only received their mounts a month previously, and they would not have much more time to complete their familiarisation – in the event the squadron had only 4 days of preparation before war descended in the island, one of which was a holiday.

In addition, VMF-211 was only at half strength, having left 12 more planes and pilots at Ewa on Oahu due to the insufficient facilities on Wake. Revetments would be ready by 1400 on the 8th (due to the International Dateline, this was the 7th in Hawaii), but taxiways would take longer, and the parking area was too small to allow for effective dispersal. With radar yet to be provided for Wake, four-plane dusk and dawn patrols were ordered and a lookout was posted atop the island’s water tower, with a phone line back to the air-ground radio operator. A squadron of PBY-5 Catalina flying boats, VP-11, was due to transfer to Wake in mid-December but thus far only an advanced party of the ground crew had arrived.

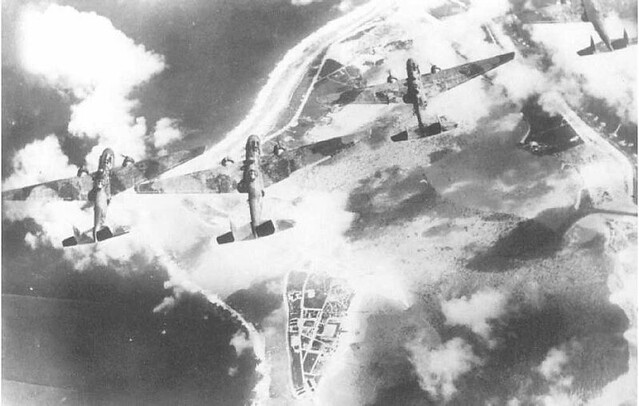

Japanese air forces in the region were in the form of Vice-Admiral Eiji Goto’s 24th Air Flotilla, based in Truk and the surrounding islands. Support of the Wake operation was delegated to the Chitose Kokutai, commanded by Capt. Ohashi Fujiro, with 36 G3M bombers and 48 A5M fighters – together designated the ‘Wake Island Attack Unit’ – and the Yokohama Kokutai with 24 H6K Type 97 flying boats. For the Wake operation, the G3Ms were based at Roi. Unusually for a unit so close to the point of attack, the Chitose was equipped with the second-string Type 96 bomber instead of the newer, more capable G4M Type 1. One of the G3Ms had carried out a reconnaissance flight to Wake on the 4th of December, its presence not being detected by the Americans. The Type 96 fighters were also second string, and did not have the range to escort the bombers all the way to Wake. They would play no part in the battle.

The two air units would support the Navy’s Wake Island Invasion Force, with 3 cruisers, 6 destroyers, 2 submarines and four transports. The Japanese plan called for the capture of islands like Wake, Guam and Makin in the Gilbert Islands in order to establish a chain of unsinkable aircraft carriers that could harass any American move west, causing damage before the anticipated ‘decisive battle’ somewhere near the Philippines. Both Guam and Makin fell after meagre resistance, but Wake would prove a sterner test for the Japanese.

Combat

The first raid was conducted on the 8th, although due to the International Dateline this was actually just a few hours after the Pearl Harbor raid. All 36 Type 96s from the Chitose Ku were dispatched, in 3 Vs of 12. VMF-211’s airborne CAP was in the wrong position, having moved from south of the island to the north just before the Japanese arrived, and heavy cloud obscured approaching planes. The F4Fs were out of radio range and would not get a chance to intercept the bombers. Their approach unobserved by the Americans, the first echelon bombed the airstrip area and surrounding parking areas. 7 F4Fs were destroyed on the ground, and two pilots were killed attempting to reach their planes – dispersal was not in effect due to the revetments being unfinished. Another pilot sustained mortal wounds, and 20 crewmen were killed, including all of VMF-211’s aviation mechanics. To further add to their woes, another F4F cracked up on landing, leaving just four serviceable Wildcats.

After this raid, a noon patrol was instituted on the basis that a plane leaving Roi at down would arrive at Wake around midday. This strategizing paid off immediately the very next day, as the Chitose bombers arrived at 1145, with 26 aircraft. They were spotted by the water tower lookout, who informed the air-ground radio operator. 2 F4Fs attacked, with TSgt Hamilton and Lt Kliewer sharing credit for a bomber. Further damage, however, was done to Wake’s already limited anti-aircraft batteries.

On the 10th another noon attack occurred. VMF-211 again was in the air waiting for the Japanese and dived into the attack with Capt Elrod claiming 2 bombers downed, although postwar records confirmed only 1 loss on this raid. For the Japanese the 3 days of bombing had proved a ‘cakewalk’ due to the very limited defense offered by the Wake Island defenders, so hopes were high for the landings to take place on the 11th.

In the pre-dawn murk, ships were spotted offshore. Holding fire until the Japanese came in close, shore guns were able to sink a destroyer, and damage other destroyers and a cruiser. As the task force withdrew to lick its wounds, 4 Wildcats attacked with the handful of bombs available. Capts Elrod and Tharin attacked the destroyer Kisaragi, landing a bomb aft – Elrod’s plane being damaged beyond repair in the incident. Further hits were obtained on the cruisers Tenryu and Tatsuta. The Kisaragi was then seen to explode and sink, probably due to depth charges stored on deck where the bomb hit. Strafing attacks on the transport Kongo Maru resulted in damage to another F4F, leaving only 2 airworthy.

The bombers came over again around 0915, so both remaining fighters attempted interception. Lt Davidson claimed 2 Type 96s and Lt Kinney another. Finally, to wrap up a very busy day, Lt Kliewer on dusk patrol spotted and bombed the submarine RO-66, which Major Putnam reported as ‘almost certain’ to be sunk, although records show that none of the subs in the area was lost. It was theorised by the Marines that the submarines may have been guiding in the bombers on their long overwater flight, however the Japanese actually used the submarines only as advanced pickets for the surface ships.

The next few days proved quiet, as the attackers paused to lick their wounds and await reinforcements. On the 12th two H6K flying boats attacked at 0500. They were set upon by two Wildcats, with Capt Tharin shooting one down. The 13th was even quieter, with no air activity from the Japanese. On the 14th, an early raid by flying boats was followed by a noon raid by land bombers which destroyed one of the two remaining Wildcats, although the fighter’s engine was saved.

The 15th saw a dusk raid by 7 Type 97s, but was otherwise another quiet day. Another noon raid on the 16th was intercepted by the F4Fs. They claimed no victories, but provided altitude information that helped AA gunners succeed in bringing down a Type 96, and most of the Japanese bombs ended up in the lagoon. On the ground, excellent work by VMF-211’s stand-in ground crews had brought two more Wildcats back into service, so four fighters were available for the defense of Wake. These were in the air for a raid by 31 bombers on the 17th but failed to bring any down, although AA added another to their score. The 18th was another very quiet day in the air, with no enemy activity other than a recon flight.

Meanwhile, plans were underway to reinforce the beleaguered defenders. The seaplane tender Tangier was to be loaded with additional Marines, supplies, and ammunition, including a crucial air search radar, and deliver these supplies to Wake. The convoy escorting the Tangier included the carrier Saratoga, which had just arrived from the West Coast. Aboard Saratoga was a fresh Marine fighter squadron, VMF-221, with 14 F2A-3 fighters – inferior to the F4F, but useful nonetheless. The main body of the relief effort departed on the 16th. To divert Japanese resources away from Wake, the Lexington task force was to attack Jaluit in the Marshall Islands and the Enterprise force was to patrol near Johnston Island as the Saratoga and Tangier force arrived at Wake, which was scheduled for the 24th.

Back on Wake, the bombings continued. On the 19th, 27 bombers attacked, losing another of their number to AA. A PBY from VP-23 arrived in the lagoon and after an overnight stay, set off back to Pearl with what would turn out to be last letters home from the beleaguered defenders. The radio traffic generated by the arrival of a single patrol bomber raised the suspicions of the Japanese, who decided to accelerate the timetable for an attack by the carriers Hiryu and Soryu, detached from the Pearl Harbor striking force.

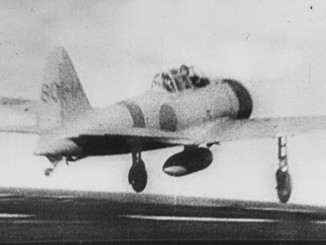

Accordingly, just two hours after the PBY departed on the 21st, Wake was attacked by a force of 29 D3A Type 99 bombers covered by 18 of the infamous A6M Type 0 fighters. The newcomers did little damage to the island in their first visit but the arrival of this new force proved ominous. VMF-211 did not get off the ground to intercept, and a reconnaissance mission by a single Wildcat did not find the Japanese carriers. 27 G3M Type 96s from Roi arrived a few hours later and had more success than their carrier-based comrades – a flight of 9 baited Battery ‘D’ on Peale Island into firing, at which point the remaining bombers swung in to attack, critically damaging one of the AA battery’s directors. The remaining guns and equipment were transferred to another battery.

On the 22nd, the Hiryu and Soryu flyers returned with 33 B5N Type 97 torpedo bombers covered by six Zeroes. Capt. Freuler and Lt Davidson were airborne dived in to attack, with Freuler quickly flaming two of the enemy bombers. Davidson was last seen attacking a group of Zeroes, but evidently was shot down as he failed to return to the airfield. Freuler, badly shot up by another Zero, managed to crash land his fighter, the last serviceable machine belonging to VMF-211 on Wake. The bombers, perhaps shaken by the aggressive attacks of Davidson and Freuler, caused little damage to Wake. A third B5N was lost when it had to ditch near Soryu, being too damaged to land.

The first combat between Wildcat and Zero proved difficult for the Americans. With no more F4Fs flyable, the officers and men of VMF-211 reported to the garrison commander as infantry. Many of them would be killed during the Japanese second, and this time successful, landing attempt the following day.

The Saratoga/Tangier group was still over 500 miles distant when the Japanese made their new attempt, slowed by the presence of a fleet oiler and the need to conduct refuelling operations. Realising the futility of forcing through a relief attempt, Admiral Pye at Pearl Harbor ordered the task force to abandon their mission, and return without flying off the relief fighters. Wake Island surrendered, after a brief and futile attempt at resistance, on the 23rd of December.

Conclusions

Even before VMF-211 lost two-thirds of its strength to the first Japanese bombing raid, it was understrength when measured against the forces arrayed against it. With just 12 Wildcats to defend against a kokutai of G3M bombers and another of H6K flying boats, the squadron needed to work with the utmost efficiency in order to maximise the chances of successfully repelling the enemy raids. Unfortunately, without radar to provide the early warning such efficiency could not be achieved. Time and again the Japanese were able to attack with little or no warning, which allowed them to reduce VMF-211’s already weak force on the very first day of the conflict and then attack with relative impunity thereafter.

The Japanese, meanwhile, had paradoxically learned the relative ineffectiveness of land based bombers in such a situation. The three days of bombing allotted had not reduced Wake’s defences enough to allow a landing attempt to be successful, and it took a further fortnight of attacks, along with strong support from two aircraft carriers, before the island could be successfully captured.

Leave a Reply