Several navies experimented with submarine-launched aircraft, but few embraced the practice as whole-heartedly as the Japanese. Throughout the 1920s several experimental aircraft were developed, and submarines modified with water-tight compartments to carry them, before the Yokosuka E6Y became the first production aircraft to be assigned to the submarine fleet in 1933. Over the next decade Japan launched several dozen submarines equipped with aviation facilities, envisaging that their reconnaissance capabilities would be of great benefit during the anticipated war with the United States. The Japanese lacked bases and large numbers of long-range reconnaissance flying boats with which to reliably detect enemy forces, and it was hoped that using submarine-launched aircraft would allow for the inspection of enemy ports for evidence of activity.

One of these new submarines was the I-25, which would have probably the most noteworthy carrier of any of the aircraft-carrying underwater craft. A Type B1 submarine, she was laid down in February 1939, launched in June 1940, and commissioned on October 15, 1941, just in time for the start of the war. Her first commanding officer was LtCdr Meiji Tagami, an experienced submariner, and she was initially assigned a single Watanabe E9W floatplane to be flown by Chief Petty Officer Nobuo Fujita. She was assigned to Submarine Squadron 1, part of the 6th Fleet, and departed for her first operational patrol on November 21. With the attack on Pearl Harbor scheduled for December 8 (Japan time), I-25 was ordered to patrol north of Hawaii and attack any ships attempting to flee from the area.

Off Hawaii in the wake of the attack which started the war, I-25 was subject to an attack by a patrol plane which strafed and then depth-charged the submarine but caused no damaged. She also participated in a fruitless hunt for an American carrier reported by one of the other submarines in the area, and suffered slight damage due to heavy seas. With the Kido Butai safely withdrawing back to Japan, many of the submarines were released for other duties. Along with I-10 and I-26, also equipped with aviation facilities, I-25 was ordered to patrol the west coast of the United States where she was assigned a patrol area off the mouth of the Columbia River, on the Oregon-Washington border.

On December 18 I-25 spotted a tanker, the St Clair, and launched a torpedo which appeared to set the ship afire. Judging the target to be sinking, LtCdr Tagami elected to leave the tanker to her fate. However, the damage to the St Clair was very slight and she managed to escape. A few days later an intelligence report indicated that three American battleships would soon arrive via the Panama Canal, and so the three submarines were ordered to the California coast in order to intercept them. The report turned out to be false, and so I-25 sailed west to return to vicinity of the Hawaiian islands. On January 8 her lookout spotted what they identified as an aircraft carrier off Johnston Atoll, which was attacked with four torpedoes and claimed as sunk. There is no record of an American ship being damaged in this location and the identity of this target remains a mystery.

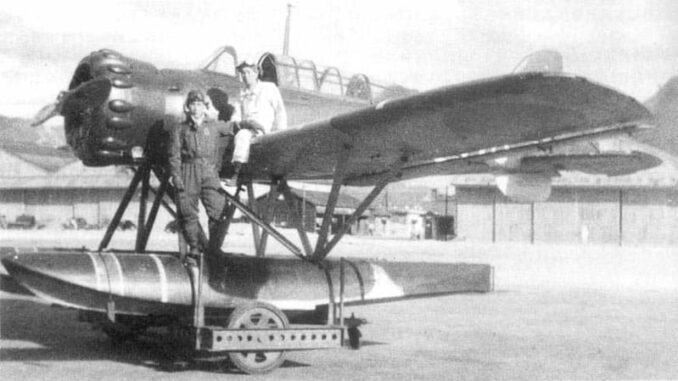

A few days later I-25 arrived at the submarine base at Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands, where she refuelled and reprovisioned. She also received a brand-new aircraft to replace her E9W, the first of the Yokosuka E14Y Type 0 aircraft to reach the fleet. I-25 suffered minor damage during the American attack on Kwajalein on February 1 when she was strafed by SBDs, but she was nevertheless able to set sail in pursuit of the Enterprise – albeit in vain.

Airborne Reconnaissance

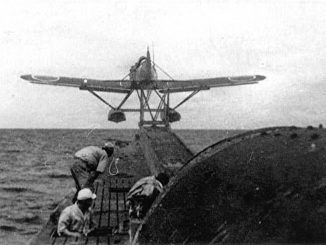

Her second war patrol would prove to be even more eventful than her first. I-25 was sent south, with orders to use her floatplane to carry out reconnaissance flights over several ports in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands. She departed Kwajalein on February 8 and began the 2,700 mile cruise to Sydney, Australia. Poor weather delayed the first flight of her floatplane for several days, but finally before dawn on February 17 the skies cleared and Fujita’s Type 0 was prepared for flight before being catapulted over the bow of the I-25. The little plane first overflew Botany Bay, to the south of Sydney, before crossing the city itself and investigating shipping in Sydney harbour and its naval base. North of the harbour, Fujita turned back out to see and headed back to I-25. At first the pilot could not find his mothership, but dye markers were released into the sea to mark her position. Having been safely recovered, Fujita reported sighting 23 ships including several major warships.

Next, I-25 moved south to take a peek at the shipping in Melbourne harbour. Fuijta took to the air again on February 26 but in cloudy conditions strayed rather close to the RAAF base at Laverton. Two fighters scrambled to intercept but failed to find the little plane. A nearby anti-aircraft battery also spotted Fujita, but did not get permission to open fire. Having escaped destrucition, Fujita and his radioman, Petty Officer 2nd Class Okuda Shoji, counted 19 merchantmen and several warships before returning to I-25. Four days later, the E14Y was in the air over Hobart, capital of Tasmania, where 5 ships were spotted.

LtCdr Tagami then took I-25 east to reconnoitre the major ports of New Zealand. Bad weather and rough seas prevented the first attempt, but on March 8 Fujita and Okuda flew over Wellington. As I-25 withdrew from the Cook Strait she spotted a steamer but Tagami refrained from attacking, preferring to make a clean escape. Four days later off North Island the submarine was spotted by two patrol craft, but survived the subsequent depth-charging without taking any damage. The following day, March 13, Fujita’s E14Y was once more airborne to overfly Auckland harbour, where he sotted four merchantmen. Whilst he was airborne I-25’s crew spotted another merchantman, and as soon as the floatplane returned Tagami elected to attack it with torpedoes. The target was reported as sunk, but no Allied losses are recorded. Three days later, as the submarine made its way toward Fiji, a cruiser was sighted escorting a merchant ship. As Tagami made preparations to attack, the cruiser changed course forcing the I-25 to dive and lose contact. Fujita took his plane into the air hoping to find the ships, but to no avail.

Arriving off Suva on March 19, Fujita made another pre-dawn reconnaissance flight, reporting a British cruiser in the harbour. The E14Y was spotted and illuminated by searchlight, but Okuda used his signal lamp to flash a Morse message in return and the light was extinguished. Four days later I-25 was off Pago Pago in American Samoa, but the sea was too rough to permit launching her seaplane so instead LtCdr Tagami crept close in to conduct a periscope reconnaissance of the harbour. Nothing of note was detected, and I-25 terminated her patrol and made her way to Truk. After refuelling, the submarine headed back to Japan for a refit, arriving at Yokosuka by April 4. There, she entered drydock. Whilst under repair I-25 escaped unscathed when American bombers on the Doolittle mission damaged the nearby aircraft carrier Ryuho.

The reconnaissance conducted by Fujita and Okuda provided information for the planners of an audacious attack on Australia. As part of preparations for the Battle of Midway, the Japanese planned to launch attacks on widely seperate locations in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans. The western portion of the attack focussed on the recently occupied island of Madagascar whilst the eastern portion selected Sydney on the basis of I-25‘s work. The plan called for midget suubmarines to penetrate the harbour and torpedo Allied warships as they lay at anchor. Two additional aerial overflights were conducted by E14Ys from I-29 on May 21 and I-21 on May 29, before midgets from I-22, I-24 and I-27 began their approach later on the 29th. Only one midget managed to enter Sydney Harbour, where she fired a torpedo at the American cruiser Chicago which missed but sank the nearby depot ship HMAS Kuttabul. None of the midgets returned to their mother subs.

Repairs completed, I-25 was ready to begin her third war patrol by May 11. She was assigned to the “Northern Force” which was tasked with carrying out Operation AL, the invasion of the American-held Aleutian islands. A week before this operation was due to take place, on May 27, CPO Fujita was again to pilot his E14Y over an Allied port – on this occasion Kodiak, in Alaska. Whilst making preparations to launch her seaplane, I-25 spotted an American cruiser at close range. Unable to cast off the aircraft, and unable to dive with it still mounted on the catapult, LtCdr Tagami was prepared to engage in surface combat with the cruiser until it became evident that the Americans had not seen the submarine in the poor weather. After the cruiser departed, the floatplane was launched, Fujita and Okuda reporting 11 warships and 6 merchants in port.

Thereafter I-25 and her sister I-26 were ordered once more to the west coast of North America. I-25 unsuccessfully attacked a transport with torpedoes on June 5, before managing to hit and damage the British steamship Fort Camosun off Cape Flattery, Washington. The Canadian corvettes HMCS Quesnel and Edmundston picked up her crew, and the ship was towed into Puget Sound for repairs. The Fort Camosun not only survived this attack, but also survived being torpedoed by I-27 in the Gulf of Aden in December 1943.

The Fort Stevens Attack

On June 18 LtCdr Tagami received special instructions from his squadron commander – both I-25 and I-26 were ordered to bombard targets on the coast. I-26 was to attack a radio direction finding station at Hesquiat, on Canadian Vancouver Island, whilst I-25 was ordered to strike a suspected submarine base located at Astoria, Oregon. Both attacks were to take place on June 21.

On that evening, I-25 approached the coast by following fishing boats, thus avoiding potential minefields, and arrived about 8 miles offshore. Unsure of the location of the submarine base (which in actuality had been approved but not yet built) Tagami selected as his target Battery “Russell” at Fort Stevens, located at the mouth of the Columbia River on the Oregon-Washington state border. Fort Stevens dated back to the Civil War and housed a collection of large-calibre coastal defence guns, albeit most of them ancient and obsolete. As midnight approached, I-25 cleared for action and commenced firing. After the first shells arrived a blackout of Fort Stevens was ordered, depriving the gunners of any reference points to aim at. As a result, most of the rounds landed harmlessly in swampy ground, with a few finding the fort’s baseball field. The only meaningful damage occurred when telephone lines were severed, and there were no casualties or injuries to personnel. No fire was returned by the fort’s guns because it was realised that the submarine was out of range of the elderly weapons available. After 15 minutes and just 17 rounds fired, I-25 withdrew out to sea.

The following day a USAAF A-29 Hudson patrol bomber on a training mission spotted the submarine and attacked with bombs, but they fell wide of the mark and Tagami was able to submerge his boat unscathed, before withdrawing further out to sea. I-25 briefly returned to the vicinity of the Aleutian islands, before ending her patrol and setting course for Japan. On July 17 she returned once more to Yokosuka to refit and carry out minor repairs.

Leave a Reply