The US Army Signal Corps was increasingly interested in radar during the late 1930s. This new technology offered to solve a number of problems, including simplifying the problem of finding enemy aircraft and directing searchlights and anti-aircraft batteries onto them. In 1937 an initial demonstration of one of the first Signal Corps radar successfully tracked aircraft in and out of New York. The same set also managed to successfully illuminate a blacked-out bomber, by directing searchlights on to it. The USAAC Chief of Staff wanted the design put into full production but the Signal Corps resisted, wanting to produce a more polished design fit for front-line use.

The design that resulted was was the SCR-268. This was a relatively primitive radar, consisting of a pair of antenna for establishing direction and elevation of targets. The set operated on a 1.5m wavelength, with a power output of about 75kW, which was good for a range of about 22 miles – perfectly adequate for searchlight or anti-aircraft gun laying. Its directional accuracy was initially quite poor, with an error of about 12 degrees, but the implementation of an electrical technique known as ‘lobe switching’ improved this to around 1 degree and made the set suitable for director control in place of existing visual and acoustic methods.

In November 1938, the first SCR-268 was shipped to Fort Monroe for trial that was witnessed by future AAF chief BrigGen Henry H. Arnold. The set was supposed to locate a B-10 bomber and direct a battery of searchlights onto it. At the appointed time, the AAF liaison officer announced that the plane was in position, however the SCR-268 operators could see nothing on their scopes in the appointed area. Searching further out, the radar crew noticed a contact some distance away over the Atlantic Ocean. This was the B-10 – the plane’s navigators were well out of position due to a strong headwind. It was an hour before the B-10 arrived over Fort Monroe, and even then it was obscured by cloud. However, when the plane momentarily flew through a gap in the clouds, it was immediately illuminated by the radar-directed searchlights, proving beyond all doubt that the concept was sound. Arnold was sold, and the SCR-268 was ordered into production.

The SCR-268 could be connected to the Sperry M-4 mechanical gun-director for automatic direction of fire. The M-4 was a mechanical computer which received as inputs the direction, speed and altitude of a target, and output the azimuth and elevation to which a gun or searchlight should be trained in order to hit the target. The M-4 was designed for optical tracking and was not well suited for integration with the SCR-268, but in the absence of any suitable alternative it was pressed into service nevertheless. The SCR-268/M-4 combination was only able to accurately direct guns to within about 200m of the target – not ideal for American anti-aircraft guns, which had a burst diameter of up to 50m (for 90mm gun). Still, this was a marked improvement over visual or acoustic tracking

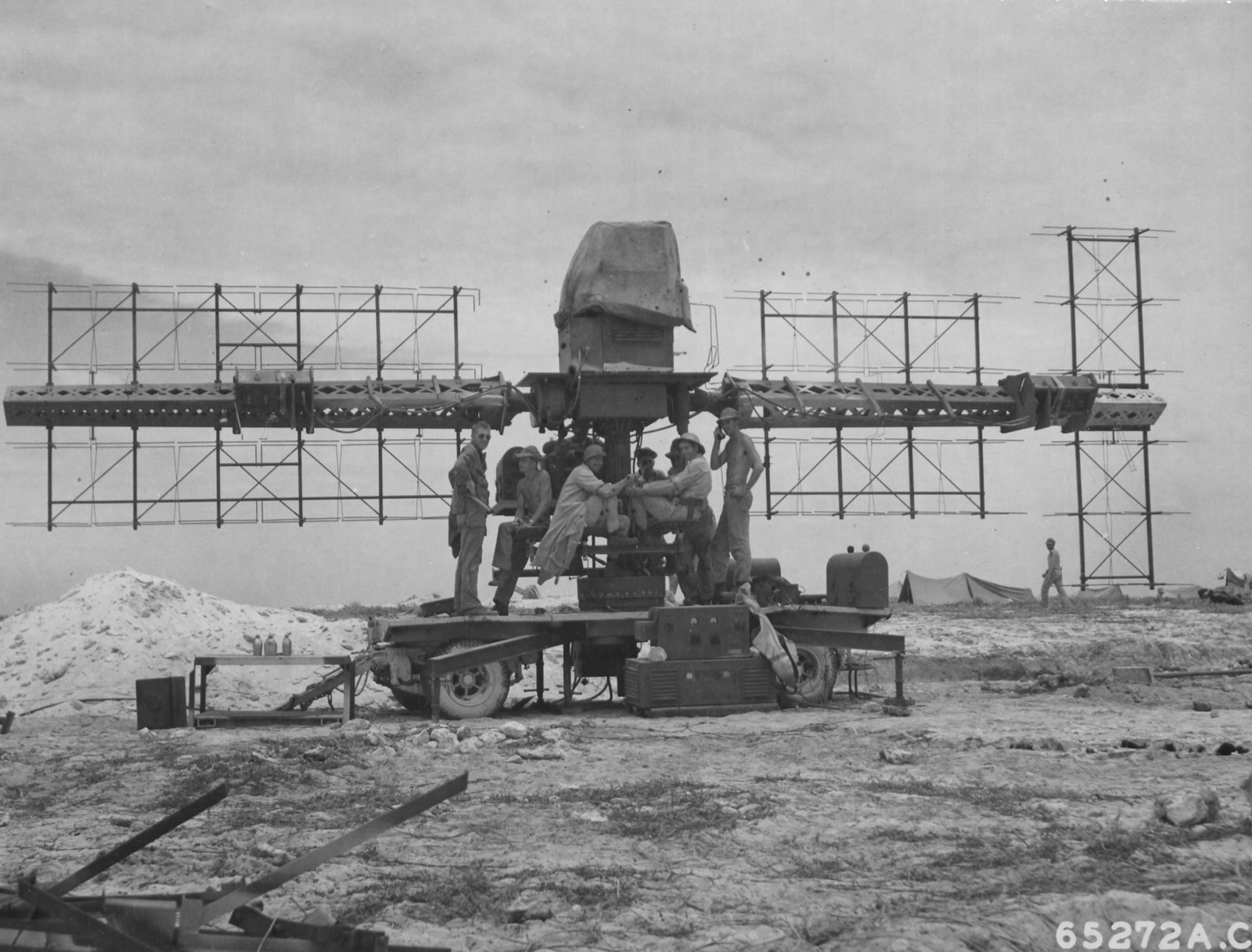

It was two more years before the prototype SCR-268 was made ready for service, with portable units suitable for operation by troops in the field. This included combining the three antennae of the prototype (transmitter, receiver and elevation) into a single apparatus that could be loaded onto a truck for transportation. As it was the set weighed over 80,000 pounds, and four prime movers with trailers were required to haul all of the equipment which made up the 268 – two to haul the radar pedestal and the antennae, one for the generator that powered the set, and one for an electrical transformer.

In addition to being supplied to Army anti-aircraft battalions, SCR-268 sets were also supplied to US Marine coastal defence units. The first SCR-268 to be deployed abroad was landed with the 5th Marine Defense Battalion at Reykjavik, Iceland, when the British handed over responsibility for defence of the island to the Americans. In mid-1941 deliveries of SCR-268 sets to the Pacific began. Sets were earmarked for Oahu, Wake and Midway, although the set for Wake was not delivered before that island fell to the Japanese in December 1941.

Another set was supplied to the Marine detachment in the Philippines, but this SCR-268 was ultimately captured. The Japanese eventually produced a near-copy, and this was eventually manufactured as the Mark 4 Model 2. The first of these was deployed to Rabaul in 1943. Additional SCR-268s were sent as part of the reinforcements for the Philippines, but these did not arrive before the Japanese had effectively gained control of the islands. The sets were eventually turned over to the Australian army. Lacking suitable directors for their lights and guns, the Australians converted their SCR-268s into air-search sets called ‘Modified Air Warning Devices’ (MAWD) and used them with good success on the northern coast of Australia. The Signal Corps later followed this example and adapted the 268 for early warning of low-level attack, creating the SCR-516.

During the build-up to the June 1942 battle for the island, Midway received a total of three SCR-268 sets, one for each of the 3-inch anti-aircraft batteries assigned to the island. Manned by the 6th Defense Battalion, these contributed to the relatively high losses sustained by the Japanese strike force, claiming 10 aircraft shot down in a frantic 17-minute barrage. Other SCR-268s were landed at Guadalcanal with the 3rd Defense Battalion, and contributed to the defence of Henderson Field by the Marines. Radar directed 90mm guns were responsible for the shooting down of several of the G4Ms that mounted regular raids on the airfield. During the July 1943 landings on Rendova, heavy air counterattacks by Japanese aircraft were countered by SCR-268 directed 90mm batteries. In one notable attack, the 9th Defense Battalion claimed 12 out of 16 bombers shot down with just 88 rounds expended.

The SCR-268 remained the primary fire control radar of the US Army and Marine Corps until mid-1944, when it began to be replaced by the superlative SCR-584.

Leave a Reply